For many in the rap game, “keepin’ it real” has become little more than an auto-repeat catch phrase to be shouted insistently at certain intervals on one’s comeback album. Or a talisman tattooed across a precision-sculpted forearm and flaunted during the photo sessions required to keep one’s street cred in line with one’s bank account.

And then there’s 50 Cent, whose realness quotient and boulevard bravado have made him the undisputed ruler of hip-hop and this year’s fastest-rising pop star. His long-awaited major-label debut, Get Rich or Die Tryin’ (Shady/ Aftermath/Interscope), sold more than 2 million copies in its first three weeks of release, spawned a Dr. Dre-produced hit single (“In da Club”) that has presided atop the charts for seven straight weeks and has served notice to the rest of the rap world that bling is no longer kingthat gangsta has now been taken to a whole new level of brutal authenticity.

By now, 50 Cent’s violent life story has been elevated to the level of urban legend, even among those who don’t follow the genre. 50 (given name: Curtis Jackson) was raised on the mean streets of southside Jamaica, Queensborn to a crack-dealing mother who would die at the hands of rivals by the time he was 8. By the relatively tender age of 12, 50 would also be working in the trade, living a schizophrenic double life as a student by day and increasingly hardened ghetto kingpin during the 3-6 p.m. time slot when he told his grandmother (who had assumed the role of his legal guardian) he was enrolled in an after-school program.

After several arrests for drug possession, a few transfers among various New York-area high schools, and multiple prison stints, 50 had constructed a fearsome reputation as the kind of criminal you don’t crossa real-life gangsta with the bankroll and firepower to match (by the time he turned 18, 50 was reportedly doing a lucrative enough heroin and cocaine trade through his network of affiliates to net $5,000 a day). But increasingly, 50 was sensing that he needed to find an alternative to the Thug Life in order to escape alive and began to pursue a rap careerpreviously, little more than a hobby he shared with friends in earnest.

50 connected with neighborhood hero Jam Master Jay from Run-DMC in 1996, who, in turn, produced his first unreleased album and introduced him to the industry figures who could help 50 leave the Life behind him. As it so happens, this was easier said than doneJay himself would be killed execution-style in a Queens recording studio (and 50 investigated for his connection to the murder) six years later.

By 1999, 50 Cent had signed to Columbia records and recorded his debut, Power of the Dollar, which included a single (“How to Rob”) that would cement his reputation as a rapper to be reckoned with. The track hilariously and boldly plotted 50’s plans to stick up various big-name rappers and singers (P. Diddy, Will Smith, Bobby Brown, and Jay-Z were all name-checked during the rhyming spree) and created the kind of street buzz that classic “dis” records throughout rap’s storied history have often generated. The static carried over into real life: 50 would go on to provoke a running feud with rapper Ja Rule and was eventually stabbed in an altercation with Ja’s crew at a New York recording studio. But two months before his album’s scheduled release, a more violent encounter would change 50’s lifeand career trajectoryforever.

On may 24, 2000, a would-be assassin approached a car in which 50 was the passenger and proceeded to empty nine rounds from a 9 mm pistol at nearly point-blank range, hitting 50 in the chest, leg, hand, and, most seriously, in the face (the bullet pierced his cheek, passed through his gums and tonguewhere a piece still remainsand produced the woozy slur that has paradoxically given him the most unique voice in hip-hop today, a cocky, calculating sneer that slides like jelly off a hot plate). He barely survived, spending two weeks in the hospital and another two months recuperating at home before he could walk again (meanwhile, the alleged gunman was found murdered a few weeks later. The case is still unsolved). By the time he was up and around, Columbia had long since dropped him, sensing that trouble would continue to follow and refusing to issue a record that might rehash the tragedies that had accompanied the high-profile careers of similar extollers of the Thug Life such as Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur.

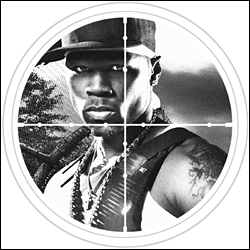

With the industry having turned its back on him, 50 started from scratch, returning to the underground and rebuilding what he’d lost from the gutter back up. Within a year, a focused and feverishly possessed 50 Cent had released five CDs of mix-tape material that sparked enough attention round the way to catch the ear of one Marshall Mathersa.k.a. Eminemwho was smart enough to recognize the sound of money when he heard it. Em declared his respect during a radio interview, a furious bidding war ensued, and 50 emerged from the experience with a single on the soundtrack to Eminem’s feature film 8 Mile (the withering Ja Rule dis “Wanksta”) and seven figures richer. His Dr. Dre and Eminem co-produced debut50’s first official release after entering the rap game seven years earlierhas, if anything, exceeded the hype his tailor-made life story initially generated, making everyone involved a stack of paper and elevating 50 to the upper echelons of the hip-hop aristocracy literally overnight. His threatening, tattooed mug is now omnipresent, leering menacingly from magazine covers, MTV, and the street-corner posters trumpeting his latest tour.

So what sort of lessons can we take from 50 Cent’s explosion into the nation- al consciousness?

It should surprise no one by now that a genre that’s marketing savvy enough to employ “street teams” to ensure that its product remains credible with its core urban audience is smart enough to turn real-life drama into a cash-register symphony. 50 Cent’s world is essentially a larger-than-life reality TV show: There are good guys and bad guys (who win more often than they don’t); some get the bling and the girls, while others get their caps peeled back. He also serves as a sort of idealized East Coast hardcore rapper, a hip-hop Mr. Potato Head taking stylistic cues from some of rap’s most charismatic figures. As Eminem himself raps on 50’s “Patiently Waiting”: “Take some Big and some Pac/And you mix ’em up in a pot/ Sprinkle a little Big L on top/What the fuck do you got?” What you’ve got is an amalgam of the most salable styles that gangsta rap has ever produceda boiling-hot brew of Biggie’s street-dealer cred, 2Pac’s raw anger, Snoop’s kickin’-shit-with-the-homies chilled-out demeanor, and the Wu Tang Clan’s gritty urban mini-dramas.

Except it’s not as simple as all that.

Ever since NWA first pioneered the ultraviolent, sexist world of gangsta rap back in the late 1980s, the question has been not when the subgenre would eventually become enlightenedthat would effectively defeat the purpose, and in many ways gave birth to gangsta’s alternative, the so-called “conscious rap” movement of the ’90s that included acts such as Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, and the Fugees. Rather, it evolved into “Where exactly is the endgame?” Artist after artist came down the pike from Central Casting with a rep more nihilistic and vicious than the last (Houston’s Geto Boys, L.A.’s Ice-T, Staten Island’s Wu Tang Clan, etc.). Eventually the extracurricular activities caught up with the artists involved, and when Thug Life and Pop Life blurred so completely as to result in the gang-affiliated murders of Biggie and 2Pac, it was clear that the rap industry required a step back in order to evaluate whether its kingmaking machinery had evolved into a death factory.

After several years of relative peace, love, and material aggrandizement from the likes of Jay-Z, Nas, and Nelly, it’s now clear that we’re back to gangsta’s glorification of guns, violence, and tales from the dark side, a realm where bulletproof vests and designer gun holsters are the new bling. Eminem recently told Rolling Stone the cold, hard truth of it all: “Kids wanna see a guy that got shot that many times and lived.” Therein lies 50 Cent’s appeal; his realness, his authenticity, is unquestionably raw and recognized.

Like the appearance of the freak at the circus, the rise of 50 Cent shows us with unflinching candor that our human craving for the ugly and the violent eventually stops at one unmitigated truth: Since Biggie and 2Pac’s senseless but inevitable deaths, ain’t a damn thing changed ‘cept the names.