This summer, musician Emmanuel “Vinny” Miranda had an angry conversation with a girl that ended with him hanging up the phone. “I was like, ‘Well, forget this,'” says Miranda, a 10th-grader at Todd Beamer High School. Pissed, he grabbed a pencil and wrote some lyrics about how the girl was “all alone/With nobody in your life to call your own.”

That’s where the story would’ve ended for most jilted teenagers. But most jilted teenagers aren’t “Juanny Cash, the 15-Year-Old Johnny Cash Prodigy,” as Miranda is billed at his weekly gig at downtown’s Can Can nightclub. As it turns out, he recently had a recording session with John Carter Cash, son of Johnny. His lyrics are now immortalized on a yet-to-be released CD with Dave Roe, bass-slapper for the Tennessee Three, and Jamie Hartford, who played electric guitar for the 2005 Cash biopic, Walk the Line.

Miranda’s teenage phone friend wasn’t impressed with the tune, titled “Cold Hearted Woman.” “She was like, ‘This is a mean song,'” Miranda says. “But everybody writes mean songs. Johnny Cash wrote a lot of mean songs. That’s what you write.”

Such a succinct distillation of country music could only come from somebody who’s listened to a lot of it. Miranda fits the bill: When he was growing up in San Antonio, Cash’s albums received constant rotation on the family record player. Miranda keeps a cache of rockabilly CDs and a DVD of The Johnny Cash Show in the single-story Federal Way home he shares with seven of his family members. “[Cash] has this rebel personality,” Miranda explains, his own glazed pompadour reflecting light. “He doesn’t care what people think, what people say.”

Miranda is a tall, thin kid with a faint smudge of a pencil ‘stache. He wears coal Converses, ebony button-up shirts, a dark ball cap emblazoned with “CASH,” and a pair of $8 Wal-Mart black jeans. A Jehovah’s Witness, he transforms his Friday, Saturday, and Sunday church services into miniature funerals. The rest of the week, he eschews TV for songwriting and listening to Cash. He knows how to play roughly 30 of the Man in Black’s songs and belts them out in a resonant, seismically deep voice.

“With that voice, you think, ‘Well that’s just the greatest thing I’ve ever heard,'” says Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam. In September, Gossard pulled Miranda into his studio for an “ongoing project” that has Seattle musicians reinterpreting the songs of Hank Williams Sr. “He has this incredible gift, this huge sound. And then he’s got a real fire in his eye, and he gives it up.”

Miranda owes his recent popularity to a 2005 hormonal influx. His reedy tweet lowered into a barrel-chested bass. He tested out his new low notes by sneaking up on friends and bellowing, “Hey! What’re you doing here?” He also pretended to be his father and called his high school to excuse himself from class. By early this year, Miranda had given up using his voice for evil and instead used it to busk for tips at Pike Place Market.

“I see the same gang of old guys all the time, and I look over and it’s a little dude,” says Chris Snell, owner of the Can Can. Miranda was ripping out a cover of “Ring of Fire” in front of a fruit stand, which “freaked out” Snell. “Johnny Cash died and jumped into his body. It’s one of those things where it’s happened, and you don’t know why the hell it exists.”

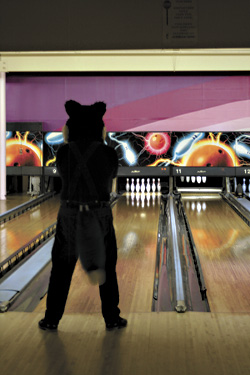

Snell hooked Miranda up with the weekly tribute gig, a roughly two-hour set of Cash covers and country songs that demonstrates a peculiar local maxim: Singing about shooting women in “Cocaine Blues” is OK, but singing about shooting canines in “Dirty Old Egg-Sucking Dog” isn’t. “Chris was like, ‘Don’t sing that one here. People love their dogs here in Seattle,'” says Miranda.

Snell also connected Miranda with a lyrics coach, ex–Vendetta Red guitarist Michael Vermillion. Being a churchgoer with a happy childhood, Miranda hasn’t experienced the years of misery, violence, boozing, whoring, and all the other good stuff that goes into country music. Vermillion helps him overcome that deficit by channeling the energies of Miranda’s bleak, teenage worldview.

Their first song, 2007’s “Since You Been Gone,” takes the plot of “Folsom Prison Blues” a little farther down the line. It tells the story of a man fresh out of prison who is horrified with how “this world’s cold and the war’s worse and people are dying and there’s hunger and…a whole bunch of bad crap,” says Miranda, who conceived of the idea while watching the news. Their latest effort, “Closer,” details problems Miranda has at home that have him lamenting the “lives that I put on the line/And the hearts that I’ve broke with my lies.”

“He’s just got a good ear for storytelling and the sense of loneliness that a lot of old country classics carry,” says the 30-year-old Vermillion, who no doubt appreciates Miranda’s tone, having once written a love song about burying somebody alive.

Before he could record with John Carter Cash, however, Miranda had to convert his fellow Jehovah’s Witnesses to rockabilly. His appearances at a club that also put on weekly “I See London, I See France” cabaret shows had already raised some hackles. He says fellow Witnesses approached his family at church to relay the message, “He can’t sing here.”

In Miranda’s faith, doing anything that takes “too much” time away from the church is sinful, he says. Pop and rock careers are especially bad. Anytime the church wants to demonstrate the corrupting influence of music, it can point to Jehovah’s Witnesses such as guitar-masturbating Prince and creepy sleepover host Michael Jackson. But Miranda had a response ready for the doubters: Johnny Cash elevates the soul.

“Yeah, some of his songs are about cocaine and shooting people. But if you really listen to them, they have a message,” he says. “‘Cocaine Blues’ starts with ‘I took a shot of cocaine/I shot my woman down.’ But in the end, if you notice, it says, ‘Lay off that whiskey and let that cocaine be,’ right?” Miranda’s arguments mollified most of the flock. Still, he wasn’t able to travel to Tennessee until Snell, who’s now his manager, promised his parents they could veto any gig that conflicted with their church beliefs and schedule.

Touching down in Nashville, Miranda recalls being, “like, speechless.” He, his mom, and Snell drove to the Cash property in nearby Hendersonville, where Johnny and June Carter recorded some of their later work in a small structure called the Cash Cabin Studio. Over the next two weeks, Miranda went to the cabin to sing Cash tunes and some originals, all the while looking at a portrait of June and Johnny that hangs on the wall.

Miranda also recorded two bonus tracks in Spanish, “Anillo del Fuego” (“Ring of Fire”) and “Mantengo la Linea” (“I Walk the Line”). “Country music’s been trying to break the Spanish market forever,” explains Snell. “The idea behind [the Spanish music] is so it will allow us a potential on mainstream country radio.”

One day during his two-week stay, Miranda and John Carter took a ride around the verdant country property, passing a well-stocked fishpond and herds of European fallow deer until they wound up in front of a blackened square of earth. It was the footprint of John Carter’s childhood home, which had been serving as the House of Cash museum until it burned down this April.

“It was pretty sad,” says Miranda. “He’s just looking at it, and it’s all gone. We both just stared at it for a while, kind of like a moment of silence. It was cool.”