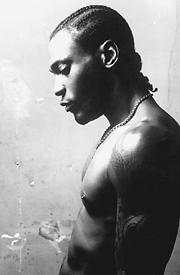

WHEN D’ANGELO TOOK OVER America last year, he seemed like a mirage— shimmery and beckoning, too good to be true. After years of relentless major label garbage, fake soul crooners, and R&B boys in stupid suits, D’Angelo materialized out of nowhere. He exuded trouble: so sexy that to watch him and listen to him at the same time seemed hazardous. In a field of overdressed imitators, D’Angelo distinguished himself by always being half-naked and always sounding like the real real thing.

D’Angelo

Pier 62/63, Sunday, August 13

Voodoo sold millions and caused a full-fledged D’Angelo season. For a while you couldn’t walk through Belltown or Capitol Hill without hearing some rich type in a tricked-out VW bug blasting it. The more records he sold, the more critics pondered the possibility that he was an overproduced illusion: Maybe D’Angelo isn’t the real thing. Maybe he’s a flash in the pan. Like Macy Gray, D’Angelo was considered neo-soul, evoking a mood a lot like the greats of the past—Marvin, Stevie—but a kid. He wasn’t “original.” He was a hybrid, a ghost, a reincarnation.

The truth of the matter is D’Angelo is no soul imitator, rather he’s soul music’s blessed son—the child who listened to the stories the adults were telling, the one who remembers everything. Who would want to be original with such a legacy and such an ability to access it? D’Angelo wears history on his sleeve, or more accurately in his liner notes: “We have come in the name of Jimi, Sly, Marvin, Stevie, all artists formerly known as spirits and all spirits formerly known as stars.” As soul’s Greatest Generation dies out or edges toward retirement, the precocious kid arrives with the keys to the kingdom. Trust me, trust me, he says. I can take over the business.

Yet if D’Angelo claims to be following the trail blazed by musicians before him, his music and lyrics consistently veer off course from anything familiar. He’s far less accessible than his forefathers, and where soul proper can be understood as music that brought people together inside some sort of post-civil rights mothership, D’Angelo’s soul is the soul of alienation and disorientation. He speaks in code. He’s cryptic and dream-addled. He’s almost too beautiful for this world.

Nevertheless, the fans believe in him, worship him, and spend way too many hours speculating about his well-being and his private life. Chat rooms monitor news about his throat infections, which have taken him out of commission numerous times in the past few months. And if D’Angelo resembles Tupac in his wild talent and disorienting sexiness, D’Angelo’s no tough guy. He’s all sweetness, nonviolence, love, can’t we all just get along. Part of the proceeds of the current tour will be donated to a post-Columbine antiviolence group.

Hardcore D’Angelo fans, those who knew him before the rest of us did, swear by 1995’s Brown Sugar. I was an addict of Voodoo, a record that manages to perpetually reveal new layers of sound: chicken scratches, clocks ticking, skitter- ing leaves, moans, noises one might encounter at the blue center of a tropical hurricane. Of course I played it so many times I can’t listen to it anymore. I’ll wager the Pier audience this Sunday will contain dozens of restless women who did the exact same thing.