Fat Joe and his DJ Khaled were sitting poolside in Miami this summer when inspiration struck. “Lean Back,” Joe’s rumbling hit with his Terror Squad cronies, had been steamrolling its way up the Billboard singles chart, and the time had come for the inevitable remix, which would shore up the song’s street cred while the TRL masses perfected their rockaway dance to the original. Joe turned to Khaled and asked the question that we’re all sometimes forced to ask ourselves: “What would Diddy do?” That is, how would P. Diddy, self-styled inventor of the remix, make this improbably hot song even hotter? The answer came clear as day. “First we’ll get Ma$e,” Khaled said. “And then . . . we’ll get Eminem!”

Eminem? On a remix? As if. Those 16 bars are yeoman’s work, the type of dues-paying responsibility he leapfrogged past five years ago when his debut single, “My Name Is,” bypassed urban radio on its way to becoming a TRL staple. The remix verse is occasionally a favor bestowed, but more often it’s a necessary obligation, a way for a rapper to keep his star bright on the back of other people’s success.

Maybe Em had been turning down requests for years. Or maybe no one ever asked him for the favor, assuming he was too busy, too famous, too white. Whatever the case, something funny happened this time out: Eminem said yes. There he was batting second on the remix—”You don’t want no drama with the blond bomber/Original don dada of the blond bottle”—trying his best to fit in just four months before the release of his fifth album, Encore (Aftermath), working hard at being inconspicuous. The special kid just wants to be normal again: Can Marshall come down and play?

It’s a transformation he’s been attempting ever since the image cleanse that was 8 Mile, his first public attempt to shirk his celebrity and return to the pre-fame womb. Granted, it’s difficult to hide inside a Hollywood blockbuster, but Marshall Mathers certainly tried. 8 Mile was all about valorizing the type of MC Eminem once was—a scrappy, outcast one—back when his whiteness was a hindrance, not a privilege.

“This is a dream for me,” he told Vanity Fair recently. “But the whole new slew of problems that I never expected that came along with it . . . I would take a lot of it back. I would take it back to where I made a comfortable living. To where I would just make music, have people appreciate it, even if it’s [just] a few.” Typical grumblings of the famous? Sure, but he’s slowly been putting his gripes into practice. In the two years since 8 Mile, while his protégé 50 Cent built an entire empire, Em was voluble by his absence. He’s been holed up in Detroit focusing his energies on becoming a model suburban parent, only poking his head out for the odd concert—his sole 2003 shows were a pair at Ford Field, home of the Detroit Lions—and, notably, for the battles against Benzino/The Source and Ja Rule/Murder Inc. last year.

Though he apologizes for his role in perpetuating those beefs on “Like Toy Soldiers,” off the recently released Encore, it’s clear that they got his adrenaline pumping; the mix-tape songs of that era are among his fiercest work. They were Eminem denuded—no Slim Shady, no sociocultural pyrotechnics, no white privilege. They bore precious little resemblance to the songs—the diarylike ones or the flippant ones—that had kept him so successfully in the spotlight.

Eminem had always milked his pain for public gain, but the emotions here felt less tested, less firm. In returning to the fray, he was effectively giving up the advantages he’d been afforded as a pop icon. His splitting seams began to show, a remarkable thing for someone typically perceived to be immune to all sort of attack. When, in an attempt to undermine his credibility, The Source released recordings of Eminem using the N-word on wax as a 16-year-old, the sting was clear. “What else could be Eminem’s Achilles’ heel?” he mused to Rolling Stone recently, a simultaneous acknowledgment that he’d been beyond impeachment for years and that the attacks hurt. 50 Cent race-baited Em on a recent MTV special: “People are always gonna show up for whatever you do.” Em’s recent public appearances, though, seem carefully calibrated to undermine even his most ardent supporters. On MTV and BET, he’s been uniformly dour, staring at the floor while suffering inane questions. At his “Shady National Convention,” a mock political rally that was merely a thinly veiled launch party for his new satellite radio station, he was unfocused and, worse, unfunny. This is no way to thank the fans. Or keep them.

But one listen to Encore and it’s abundantly clear that’s not on his agenda anyhow. Though easily his worst album, Encore might be Eminem’s most brilliant ploy yet: an album primarily about, and responding to, what the public thinks an Eminem album should sound like. It’s almost an active dialogue. Nearly every song is a challenge, beginning with the lead single, “Just Lose It,” a lazy amalgam of Em’s prior hits that snipes at Michael Jackson, Pee-wee Herman, and in the video, MC Hammer, banal targets all (“It was the last record we made for the album,” he told Rolling Stone. “We didn’t feel like we had the single yet. That was a song that doesn’t really mean anything.”)

Like “Just Lose It,” much of Encore is catchy in the most basic way—he and Dr. Dre still have a gift for uncanny hooks—but it’s also a conscious rejection of his oeuvre, a self-critique most artists don’t go through in private, much less lay bare for public scrutiny. “My 1st Single” has all the hallmarks befitting its title— celebrity-skewering rhymes and insistent, scratchy beat—but they merely decorate the sound of Eminem unraveling, rhyming monosyllabic grunts and boasting, “Long as I got Dr. Dre on my team/I’ll get away/with murder like O.J.” Or was that confessing? Or lamenting?

On “Rain Man,” a particularly dolorous track that features lengthy disquisitions on Christopher Reeve and on what constitutes “gay,” he still manages to play with flow in remarkable fashion. “I don’t gotta make no goddamn sense,” he raps at the end. “I just did a whole song/and I didn’t say shit.” It’s only because he says nothing so artfully and so unpredictably (has he been listening to those old Anticon tapes?) that songs like this and “Big Weenie,” both of which are bewilderingly bad, aren’t fast-forwardable. No other rapper would merit such indulgence.

And as Encore confounds his audience, Eminem’s beginning to pay the dues he skipped the first time around, whether it’s squeezing between Ma$e and Fat Joe, rappers he doubtless loathed seven years ago when he was still a quick-witted battle rapper, or slowly honing his production chops, a decidedly unglamorous calling. This summer, he wrote a letter to Afeni Shakur, 2Pac’s mother, asking permission to take primary control of the next posthumous Pac album. He produced 13 of the 16 tracks on the new Loyal to the Game (Amaru/Interscope), and the pairing is fitting: Em’s beats often sound like death marches, and Pac was forever prophesying his own end.

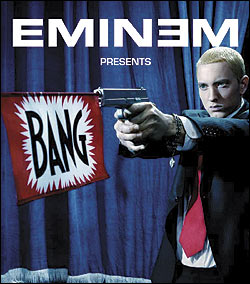

These are the signs of a man given to abnegation. He doesn’t want to conquer rap again. Rather, he wants to become part of its fabric, to become unremarkable. And to do that, he has to lay waste to the legacy that he’s made. So is Encore his retirement album, then? Not exactly. “I got unfinished business with rap music right now,” he said on TRL two weeks ago. But despite the megalomania displayed on tracks like the anti-Bush “Mosh,” it may be some time before the old Slim Shady comes out for a spin. On Encore‘s closing skit, and in the accompanying album artwork, he opens fire on his audience before turning the gun on himself. Biggie ended Ready to Die with his own death, but it was crucial to the album’s narrative. Jay-Z had himself killed in the video for “99 Problems”—a metaphor for the death of Jay-Z and the rebirth of Shawn Carter—and that’s a better analogue for Eminem’s strategy. After 77 minutes of Encore‘s dizzy befuddling, the gunshots serve as notice not to get too close. For Em, the opportunity to ebb into relative quiet is too good to pass up. Parse all you want, he’s saying. There’s nothing to see, or hear, here.