A lot of great releases are on tap for this year’s Record Store Day, from a wide-ranging list of artists. Whether you’re into the Grateful Dead, Metallica, or Miles Davis, there’s something for pretty much every kind of music fan. But few selections will send collector nerds racing to the bins as quickly as Devo’s contribution, Live in Seattle 1981, a double LP recorded on their New Traditionalists tour that was pressed from a recently unearthed recording buried in a box by the band’s longtime archivist. The release, limited to 2,000 copies, was recorded at Seattle Center Arena, which became Mercer Arena in 1995.

We were lucky enough to get Devo’s Gerald V. Casale on the phone to discuss the record, the 1981 music scene, and why the band shied away from opening acts.

SW: What prompted you to want to release something for Record Store Day?

Casale: For me, personally, I think it’s quaint. I find it antithetical to the culture, and that I like. And I grew up buying records. The most important musical events in my life center around vinyl, when an artist actually did a body of work and you’d listen to the whole album beginning to end and took it seriously. All that stuff is gone. Even the seriousness of the artists who create content now is lacking on that level.

Do you have any sense of what Seattle’s music scene was like in 1981, or if there even was one?

It seemed like the whole Pacific Northwest—San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, Vancouver—had fantastic audiences. There was a really strong demographic of people who liked the new music, and they were great crowds.

So your sense is that it was more regional?

The way people behaved region to region was very different back then, probably because there was still regional control of radio-station playlists, independent record stores, independent film houses. Some towns had more of their own character. Now it’s like Walmart. No matter where you go, you see the same 10 hits in stores and the same playlist controlled by some central robot force.

Do you remember if anyone else was on the bill that night?

I doubt it. Back then, since we had a certain degree of respect and clout, we billed ourselves as an evening with Devo. We didn’t really like opening acts. If we had to, we always tried to get an opening act that was not a typical band. We didn’t want somebody onstage making as much noise as we were about to make, burning out the crowd’s ears. We had interesting, weird stuff. We even tried comedians and weird acrobatic acts, things that the crowd would boo at. We did have a four-piece chamber group play classical versions of our songs—that was great fun. People liked that. But our show was, like, an hour and a half long. It had a lot of lighting and set changes and costume changes. It was a very theatrical production, so we really didn’t need anything else.

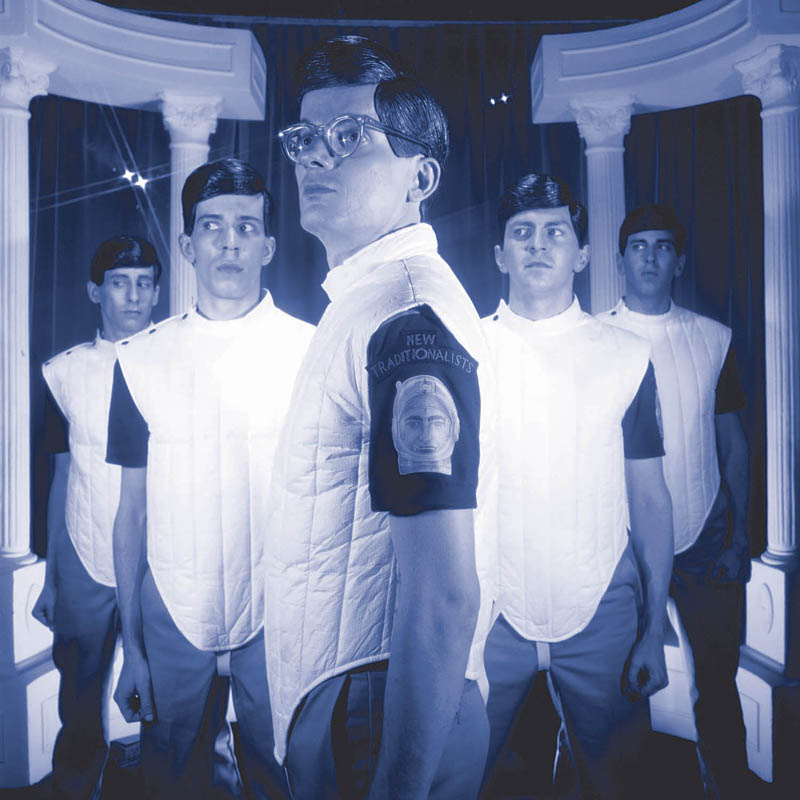

Your stage outfits on the New Traditionalists tour included a Ronald Reagan–style hairpiece and what you guys called Utopian Boy Scout Uniforms, which Wikipedia describes as a gray button-down shirt, gray slacks, and black patent-leather shoes.

I designed those Reagan pompadours. We were trying to make fun of the right-wing political hairdo. Every politician seemed to have the same hairdo. We had just come back from Japan, and we’d come across this ultra-right-wing group there called The New Traditionalists, and they sold pins in stores. Satirically, we bought a couple of those pins. As we were writing those songs, we just decided to graft the Japanese right-wing name onto those records. We became The New Traditionalists, but turned it on its ear. We appropriated the idea of that, meaning we were going to provide you with new traditions to forget about the old ones.

What are your feelings about the New Traditionalists record now as it pertains to the rest of your catalog?

I love the New Traditionalists record. I’m just sorry we had so many problems during the recording of it. There were problems with the actual two-inch tape that we were sold on by these engineers: “You gotta use this new 3M stuff.” By the time we were laying down vocals, the edge tracks were disintegrating on all the two-inch tape. We were losing everything we were spending a lot of money and time on. We had to transfer everything to the then-brand-new format of digital reel-to-reel tape and try to save what we did, because we didn’t have enough money to start over. Then we had to finish the record using digital technology back in L.A. at the Record Plant.

Are there any live records that are important to you? Do you like them?

I like them when they’re good. [Finding the bootleg] was a real surprise because on that particular tour, no professional recording was ever made. The one time we tried to record the show, it was because a seven-camera crew was shooting and their lighting generator got crossed with our stage-light generator and they blew out both sets of lights—the film lights and the stage lights. It was a disaster. And part of the insurance settlement was that all audio and video from that show had to be destroyed because they were claiming a loss.

Do you know who made the bootleg?

Somebody on the crew back then had plugged into the board and made a recording right out of the board. But luckily there was an audience mike.