OTIS TAYLOR

Bumbershoot, Mural Amphitheater, $20

12 p.m. Mon., Sept. 2

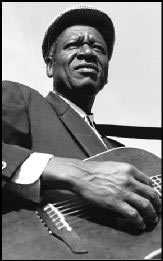

It might seem that there aren’t any great bluesmen left to be discovered, no one fit to join the ranks of Hooker, Waters, Johnson, or Patton. But dig a little, and you’ll find plenty of people willing to make a case for Otis Taylor’s name to be included in that roll call.

Like all blues greats, his music—while fitting within the framework of the genre—is an intensely personal expression, crackling with pathos and passion. And at 54, Taylor’s finally on track and receiving widespread acclaim. Not bad for a man who took a 19-year hiatus from music to work in the antique business, only to return in the mid-’90s.

On Taylor’s three post-comeback albums, including this year’s Respect the Dead, the Denver-based songsmith deals with a variety of tough topics: the murder of his great grandfather, homelessness, slavery, and depression, among other things. While this is definitely a darker brand of blues—and certainly one with a socio-political conscience—Taylor insists his agenda is simple.

“I just tell the truth. It’s history, it’s storytelling, I’m just like a reporter. That’s what a griot is, just a teller of stories, of history,” he says. “Is there any doubt that there are people hungry all over the world? Maybe I’m a poet, I guess. It’s part of being an artist, I suppose. I consider myself a blues artist, rather than a blues musician.”

That artistry is finally being recognized. This year Taylor won the prestigious W.C. Handy blues award as Best New Artist for 2001’s stunning White African disc.

“I was surprised, because I didn’t think people knew who I was,” says Taylor, who hasn’t let any of the honors go to his head. “You win, and you go on to the next thing.”

That next thing is a tour in support of Dead, with longtime bassist/keyboardist Kenny Passarelli, guitarist Eddie Turner, and backing vocalist daughter Cassie Turner. The trio’s feral live sets have left behind a trail of converts eagerly embracing the group’s stripped down, drummerless style.

“When we play live, we’re very intense, in your face, psychedelic and pulsating,” Taylor explains. “We’re very aggressive live [whereas] I try to keep the albums very sparse. One time we tried using a drummer, but it didn’t make any difference. Sometimes you can hear what we do more clearly because there aren’t any drums in it. Maybe that’s part of our technique.”

While steeped in trad blues—often echoing John Lee Hooker in his singing and the monochordal style of his songs—Taylor admits that the balance of his influences are more outr麠”I love flamenco music, Irish music, Appalachian music—those are the things that influenced me. I like Dave Brubeck jazz. It’s the [things] outside your environment that influence you, not soul music or blues, because I was raised with that. My influences are what makes my music a little different.”

And Taylor celebrates that difference often. He’s already back in the studio, working on his next album, because “I feel like I’m prolific. I came out with Respect the Dead quickly so people wouldn’t think White African was a fluke,” he says proudly. “The next one will be just as intense.”