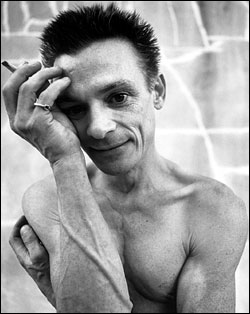

I tell Chris Whitley that his seventh and latest album, Hotel Vast Horizon, is an extremely “dark” record, and he laughs appreciatively and says “yeah” in a conspiratorial whisper, partly because it’s 11 a.m. and he’s just greeting the day, and partly because this is Chris Whitley and he’s as close to a ghost as many of us are going to come.

Hotel Vast Horizon is a scary album in much the way those mid-’70s Neil Young efforts, Tonight’s the Night and On the Beach, personified the psychic dislocation of their creator. Whitley, a onetime Sony-promoted “modern blues hero,” headed for the same ditch that lured Young away from middle-of-the-road mainstream success. But where Young could always fall back into the relative safety of Crosby, Stills, and Nash, Whitley has stood nakedly alone, recording albums of singular beauty and great emotional depth.

“Aside from the financial ills and the difficulties of touring, I can produce what I like to,” says Whitley. “I don’t feel frustrated. It doesn’t have the commercial strain of a big label. To be able to produce more, it seems more healthful. My livelihood has been my own fault, making bad moves.”

In recent years, Whitley’s become the flagship artist for the small, independent Messenger Records. His albums for the label have been revelatory in the most low-key way possible. Hardly “bad moves,” but not the kinds of maneuvers likely to attract much immediate attention.

Sadly, it’ll either take death or, perhaps, just time for Whitley to be “rediscovered” by whoever makes up the MOJO-reading crowd in 20 years’ time. But when they do finally find him, they’ll be talking about Whitley’s Messenger releases with great reverence: 1998’s Dirt Floor, an all-acoustic album recorded in one 24-hour stretch, and 2000’s Perfect Day, a completely improvisational collection. The newly released Hotel isn’t much more lavish, recorded in less than a week this past December with just a few rehearsals thrown together in advance.

Mostly, Whitley sings in a scarred and soulful wisp, with only the bass of Heiko Schramm and drums of Matthias Macht backing up his mix of sparse guitar and banjo. “When at last I was left for dead/The dissident sister took me in,” he sings on “New Lost World,” opening the album on a somber note that grows stronger with each song. Even when he steps it up a few beats per minute for “Insurrection at Newtown,” it’s to twist his sound into a Kurt Cobain-like blues lament.

“We want it to be groovier than rock-band heavy,” says Whitley. “These guys that I’m playing with have a trip-hop group out of Dresden (Tijuana Mon Amour Broadcasting Inc.) and come out of playing different kinds of stuff. We have similar sensibilities where we play really natural together. It’s quiet but not exactly mellow.”

If there’s been any constant in Whitley’s life, it’s been his obsessive need for escape. Drink and drugs created problems for years, and he’s spent more years exiled in Europe (first Belgium, now in what was East Germany) than most dishonored dictators. Nowadays, Whitley keeps it together by staying away from the business end of the music as much as possible although he’s done some soundtrack work, including German film Pigs Can Fly and the Brian Koppelman/David Levien- directed mob drama, Knockaround Guys.

His contrarian nature extends into his music as well, where he’s long refused to play the role of guitar god. “I don’t really want to listen to guitar music, but I still play it, so there’s a problem,” Whitley laughs. “I physically like playing guitar, but it’s not the sounds I listen to. I start screwing around trying to sound like a piano playing small chords. I like the minimal thing most.”

One guitar guy Whitley does admit to listening to lately is Bob Dylan, especially “Changing of the Guards” from Street Legal, which he’s been cueing up on the stereo with alarming frequency. “There are so many good songwriters out there,” he says. “But what I absolutely need from music, I get from a few essential songwriters.” If Whitley keeps making albums like his Messenger output, he may actually find himself among the essentials before too long.