The first sound on Fireball‘s Blessed Be 12-inch EP (High Roller Society) is the sound of recording gear being irreparably damaged: drummer Sue P.’s stick, obviously held in a tight fist, being rammed down onto a garbage-can-sounding snare head, as captured on a condenser microphone positioned way too close. The rest of the record is one big audio blister. Everything seems to be breaking up and covered in gray dust; the bass is so loud and fearsomely distorted that it sideswipes both guitarists out of the mix with every note.

“Properly” recorded, and with a little more “professionalism” (hwawck-PTOO) in the musicianship, the EP’s four songs (one of them a cover of Amon Düül II’s Led Zep impression “Archangels Thunderbird”) could probably pass for good early-’80s new wave, or at least early-’90s indie-pop—singer Jennifer Black double-tracks her voice and chirp-moans like she’s warming up for Pat Benatar. But the glory of Blessed Be is the sludge the band’s boots splatter everywhere—the record’s lyrics and graphics reveal an obsession with the occult, and Fireball know perfectly well that chaotic darkness is their greatest strength. So they play up the static coming out of their blown-out amps, the dribbles of white noise when they pull their fingers off their strings, and especially the floor-splintering crunch of those misrecorded drums.

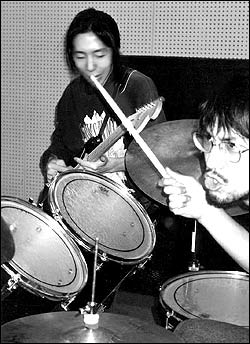

The Japanese duo Ruins begin their album Vrresto (Skin Graft) with a tribute to drum abuse, too. This one’s called “Snare,” in fact; the only elements drummer/ composer Yoshida Tatsuya allowed himself to use for it are a snare hit, into which he puts some serious body English, and a pungent chord on Sasaki Hisashi’s six-string bass. The 77-second-long piece’s back- and-forth crash-and-twang conversation is incredibly tightly composed and performed—Yoshida and Sasaki are prog-rock fanatics who live for insane time signatures and maximum speed, and they crunch numbers like actuarial robots. But the whole album’s also recorded with nasty, growling sonics: As Ruins’ conceptual descendants, Lightning Bolt, have figured out, sludge is the natural ally of tweedly hyperprecision.

Originally released in 1998 and newly remixed, Vrresto is one of two Ruins albums to have appeared in the United States this year. The other is 2000’s equally dirty-sounding Pallaschtom, which ends with three brief, show-offish strings of fragments of familiar riffs that they often perform as encores at their shows: “Classical Music Medley,” “Hard Rock Medley,” and “Progressive Rock Medley.” Yoshida’s obviously a big fan of Rush, Van Halen, and especially the European concept-prog band Magma—like Magma’s Christian Vander, his lyrics are in an invented language (“Buppairodhazz nebello schpazzkhi kyabalom sidhai viromgai,” goes the chorus of Pallaschtom‘s “Buppairodhazz”), and sung with mock-operatic grandeur. If they were going for a clean, precise sound, their songs could sound like insufferably precious études; instead, the muck of their off-key shrieks and Yoshida’s overloaded amps makes their microcomposed outbursts sound as if they are actually unpredictable.

The Colorado ensemble Biota have been investigating a different kind of murk for a couple of decades—their palette is the range of sounds that acoustic instruments can make when they’re subjected to severe electronic deformation. Their arsenal includes crumhorn, hurdy-gurdy, tubular bells, bass clarinet, and shawm, but the dominant instrument on their records is the studio. So when they were invited to the Canadian festival for which the 10-piece group’s performance is documented on the newly released Musique Actuelle 1990 (ReR)— one of only two times they’ve ever played live—they essentially brought their studio with them, processing and mixing their instruments from the stage. (The CD is credited to “Biota/Mnemonists“; Mnemonists are the group’s visual-art arm, which projected video imagery as part of the performances.)

The result has a few passages that feature people playing instruments in the conventional sense, like a little march for accordion and drums. Mostly, though, it sounds like what happens to watercolors in a precisely managed flood (which describes Mnemonists’ visual accompaniment to the package, too). The performance is populated by steady drones, wobbling gurgles, faint bending pitches, and the occasional burst of high-intensity static; they line up into zombified euphony and metrical coordination for minutes at a time, then dribble off into their own corners.

Stephen Stapleton is another veteran of the murk world—his anti-pop project Nurse With Wound has been operating since the late ’70s. The two-CD retrospective Livin’ Fear of James Last (Castle) is billed as “a Nurse With Wound variety pack,” since “hits” are not within the realm of their aesthetic. Stapleton likes to toy with sounds that normally aren’t supposed to be recorded: “Ag Canadh Thuas Sa Spèir,” for instance, starts with a minute or two of electrical buzz, incorporates some accidental digital squeals, then gradually layers on feedback, insect noises, and random clatters. Five-and-a-half minutes into the piece, an actual rock band zooms in, plays a Stereolab-ish groove for 30 seconds or so, disappears in an abrupt explosion, pops back up, then fades out again, leaving only a mist of hisses and squeaks. NWW’s work is best heard in small doses—a lot of their longer pieces are mercifully edited down here—but this selection is a museum of sludge, a display of Stapleton’s mastery of the enormous range of slippery, unruly noise.