Lil Wayne is not batshit insane.

Let’s be clear about that. Despite the fact that he regularly refers to himself as an extraterrestrial, seems to have an utter disregard for the rule of law and for his health, and kisses his surrogate father on the mouth—despite the objections of the rampantly homophobic hip-hop community—Wayne has his shit together.

Unlike just about everyone else in hip-hop, Wayne has taken the old adage “be yourself” to its logical—or highly illogical—conclusion. His new album Tha Carter III is the biggest rap CD of the year, commercially and critically; perhaps the biggest, period. That’s what can happen when you partake in a couple years of foreplay, releasing practically a career’s worth of material via mixtapes and guest appearances, as Wayne did.

See? Not crazy.

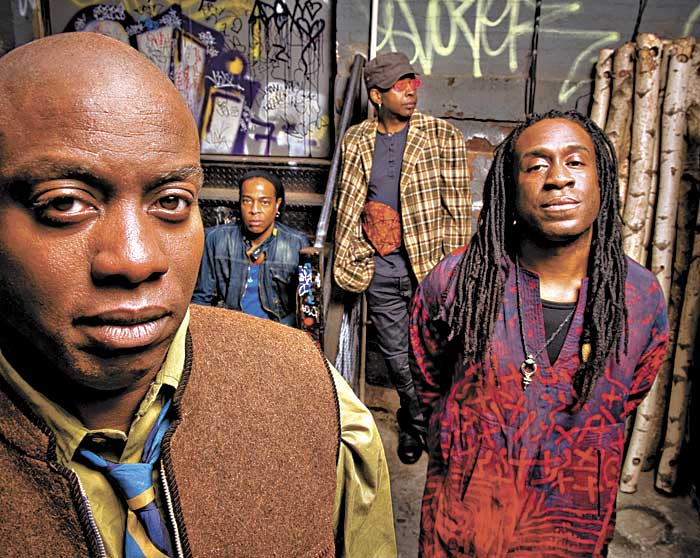

But as good as III is (more on that later), it’s just the sideshow. On the grand stage of hip-hop, the real attraction is Wayne himself. Start with his increasingly tattooed, rumored-to-be-juiced figure, which perhaps approximates that of a surly Martian. “I think the tattoos intimidate [people] and show them they’d better not walk up to me,” he explains to me. “Because I’ll knock your fucking head off.”

Move next to his unconventional voice, which can only be described as “amphibian-like.” Continue with his unorthodox approach to marketing, and finish with his hypersexualized persona. Who else could be accused of homosexuality while simultaneously being linked to video vixen/tell-all author Karrine “Superhead” Steffans?

He sucks XXL covers, blogger hype, and ‘hood hysteria toward him like a black hole, somehow earning “Best New Music” raves from Pitchfork and receiving the loudest cheers at New York radio station Hot 97’s annual Summer Jam concert this past June.

Needless to say, I’m stoked to talk to him. It takes three weeks of nagging his publicist, but we finally connect on a Friday evening as he rides on a bus through the Southeast somewhere. His voice is low and sullen, and his mind wanders when I ask him a question he doesn’t feel much like answering.

“Which track on the album are you feeling the most right now?” I ask.

“All of ’em, baby.”

He grows more animated when I ask him about his adopted hometown of Miami. “It’s perfect here,” he says. “I just like how beautiful the weather is every day, to tell you the truth. I’ve got a high-rise, so I like the views.”

But though he lives in the midst of party central, he almost never hits the town, say, in a disheveled tux bearing trunks of suckers atop which ladies can writhe, as he does in the video for his chart-topping hit “Lollipop.”

“I don’t go out much,” he says. “For what? If I do go out, it’s not even a party no more, it’s just a big ‘look at Lil Wayne’ fest. So I stay in the studio, and I get paid to party. I’m not going to go out if I’m not getting paid, so why go out if I get paid to party in the studio? And I’m 25 years of age, I’ve got my whole lifetime to party.”

He may not have much of a lifetime if he continues to sip his noxious cocktail of choice (Hawaiian Punch and promethazine cough syrup) and smoke weed all day.

But somewhere in the depths of his altered mind, there’s a Clinton-like concern for his legacy. He’s still not a household name among most mainstream Americans, after all. (Your parents almost certainly haven’t heard of him—not the way they have of 50 Cent and Kanye West.) So he’s branching out into acting, having recently finished shooting Hurricane Season, which also stars Forest Whitaker, Isaiah Washington, and Bow Wow. Directed by Tim Story (Fantastic Four), it’s a basketball feel-good that takes place in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and was shot on location in New Orleans. “It’s cool, I like it,” Wayne says of his first major thespian experience, but adds that he had trouble finding the patience that acting requires. “[T]he actual physical doing of it, I kind of had that in the bag, thank God. I was blessed with that. But it was the actual patience of being there that was difficult for me.”

Unlike full-time corporate crossovers like 50 Cent, Pharrell Williams, and Diddy, however, it’s clear that Wayne’s most concerned with his music. His commitment is almost quaint in an era where newbie rappers like Saigon and Lupe Fiasco threaten to retire, and many others claim their talents would be better employed as street hustlers. Wayne truly wants to be the best rapper alive; though he claims the title publicly, one senses that a voice in his head tells him he’s still got a way to go. “Gotta work every day/Gotta not be cliché,” he urges himself on Tha Carter III track “Dr. Carter.”

This attitude informs III, making it a departure from the tossed-off, improvised mixtapes he’s been releasing since Tha Carter II came out in 2005. And what makes III superior to those other efforts is that Wayne was forced to do some editing. Instead of relying on beats from songs that were already chart hits, the 16 tracks on the album are specifically tailored to his flow. Culled from folks like Kanye West, Swizz Beats, Cool & Dre, and Dallas’ Play-N-Skillz, the songs alternate between first-rate club-and-trance-rap (“Lollipop,” “Mr. Carter,” “A Milli”), mid-to-low-tempo ballads that allow him to crack jokes (“Comfortable,” “Tie My Hands,” “Let the Beat Build”) and guitar jams which bring real drama. The album’s highlight falls into the latter category: the Rolling Stones–cribbing “Playing With Fire,” which recalls a battle with his mother’s abusive husband and encourages his haters to assassinate him like Martin Luther King Jr. Even seeming throwaways like “Mrs. Officer,” about a raunchy affair with a cop, is given heft and humor via Bobby Valentino’s sung hook, which sounds like a cop siren. It’s a welcome update on the used-to-death cop-siren sample.

That’s not to say there aren’t plenty of stoned, off-the-dome moments on songs like “Dontgetit,” in which he babbles: “Due to the laws we have on crack cocaine and regular cocaine, the police are only”—long pause—”I don’t want to say only right, but shit, only logic by riding around in the hood all day and not in the suburbs.” He continues briefly, but then gives up. “You know where I’m going.” But for better or worse, this is all part of Weezy’s new (most would say improved) aesthetic since the days of the hurried, more predictable style that characterized II and his earlier studio output. Though he used to struggle to stay within Cash Money’s tinny-beats-and-two-dimensional-bravado paradigm, on III Wayne is completely comfortable saying whatever the hell he wants and over whatever type of music he’s feeling. (Even his own poorly played guitar.)

Much of Wayne’s charm is that neither he nor anyone else knows what’s going to come out of his mouth next. And because Wayne has finally mastered the art of knowing when to let himself go and when to reel himself in, III is a cohesive, fulfilling work.

“Are there any tracks you’re surprised turned out as well as they did?” I ask.

“Um, no, all of them are exactly what I expected,” he says. “I put my all into them, and I expect to get all out of them.”

And Wayne knows exactly what he’s doing.