“Grime” began semantic life as an insult, a term first sneered by U.K. garage DJs like Matt “Jam” Lamont to distance themselves from an undesirable underground, all stomping dancehall drums, the foghorn-blare bass of techstep jungle, and industrial textures. But after the oedipal struggle to kill U.K. garage, grime producers slowly began to embrace the pleasure principle again. Suddenly a name that invoked the ring around your bathtub started to seem a little limiting.

Plus it doesn’t capture grime’s biggest innovation: the rise of the MC. Early grime was known simply as “garage rap.” For a decade, U.K. urban culture had refracted its love of American rap and Jamaican dancehall through the aerobic tempo of rave and jungle. When U.K. garage downshifted into the slow lane, it became irresistible to its country’s fast-chatting b-boys; as a result, grime is now only a hair faster than U.S. rap. And clipped to pop-song lengths, it bears little relation to post-rave’s endless disco plateau.

However, this isn’t just U.K. hip-hop. Grimy limeys have their own slang, dress, and culture, a creole stranded in the Black Atlantic somewhere between the East End, a Kingston Yard, and the Dirty South. Plus, living at the cutting edge of rave, jungle, and garage has given grime producers a sonic palette you don’t find in Dr. Dre productions. Even with the tempos slowed, there’s a friskiness to grime—in particular, its at times piccololike bass lines and the woozy video-game pings that are as likely to pop up as door-slam drums or earth-tremor sub-bass—that is harder to come by in American rap. But, while unique, grime links hands with kissing cousins dancehall and crunk, a 110–120 bpm street-beats continuum, which some commentators have dubbed a “ghetto archipelago.”

But for most of you, I’m guessing all this breathless press has been mostly academic. That is (cue triumphant fanfare), until now. Thanks to the morally questionable but aesthetically unimpeachable folks at Vice, you can pick up the brand new collection Run the Road without a plane ticket or a Web browser. A true-blue labor of love for U.K. label 679’s Dan Stacey and journalist Martin Clark, Run the Road is not just the first grime comp available in America but one of the first grime comps widely available anywhere. Run‘s cherry-picked nature—16 tracks from a period of almost two years—makes it an essential genre document rather than simply a very good mixtape.

The opener (Terrah Danjah featuring Hyper, Bruza, D Double E, and Riko), “Cock Back (V. 1.2),” is an almost pornographic gunman anthem, right down to the clip-emptying “ka-chung” producer Terror Danjah tenderly inserts as part of the beat itself. “In East London we cock back,” they tell us, and it ends with Bruza declaring himself, in a voice equal parts Cockney and Cookie Monster, “brutal and British.” Kano’s closer “Mic Fight” is pitch-black clonking menace, rolling through council estates at night cocooned in an Escalade. Jammer’s “Destruction VIP” mashes up spybeat horns, rictus-tense strings, and a brutish 8-bit anti-groove, ugly and thrilling.

But it’s not all darker-than-thou macho bluster. Ears’ “Happy Days” is positively jaunty, a wistful little “can it be all so simple?” paean. Target & Riko’s “Chosen One” sounds weary and embattled, with its leadfooted beats and bleary strings, but Riko’s self-determination lyrics and wise-beyond-his-years voice make it a feel-good mini-masterpiece. There’s even a remix of the Streets’ “Fit but You Know It” to pull in the indie kids; it’s roundly stolen by Donae’o and Lady Sovereign. Sov, the self-described “white midget,” is tapped to be grime’s breakout star, and you’d have to have your head buried in peat moss not to hear why on the ridiculous “Cha-Ching (Cheque 1, 2 Remix).” With a flow that’s equal parts Betty Boop, Foxy Brown, Dame Edna, crunk-factory production, and a bag full of cheeky non sequiturs (a Sov specialty—see the more recent single, “Random”), she sounds set to conquer the world. (Even if there is that faint whiff of racism that, rightly or wrongly, follows a white person taking a predominantly black musical form to the bank for the first time.)

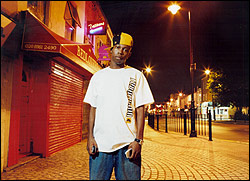

Dizzee Rascal remains grime’s biggest star for the moment, shifting 100,000 copies of his debut, 2003’s Boy in Da Corner (paltry even by current American indie-rock standards, never mind hip-hop ones), and winning the “prestigious” Mercury Prize in the U.K. Judging by last year’s follow-up, Showtime (XL), his brush with success has sent his latent paranoia into overtime. Showtime‘s hoary concept (the perils of fame, yawn) and relentlessly intelligent cockney guttersnipe vibe mark it out as something like Nas’ Illmatic meets Public Image Ltd.’s Second Edition.

I’ll resist writing out any of Showtime‘s lyrics, because if I did, we’d be here all night: Dizzee is the most quotable MC going, packing more joy in the things the human voice can do per minute than anyone else. And as a producer, he finally sounds like he could compete in America. “Everywhere” is as good or better a Neptunes rip-off as J-Kwon’s “Tipsy,” which is saying something. “Graftin” has great pneumatic nozzle drums, econo laser zaps, and Dresden bomber bassdrone. The closer, “Fickle,” makes me think of some dream collaboration between Kanye West and hardcore rave producer Acen.

Showtime was easily the best album of 2004; barring a mind-blowing summer, Run the Road will probably be the best album of 2005. Grime may yet blow up the U.S., but I wouldn’t hold my breath. It can’t even seem to blow up England, where press and public alike seem content with the one-note joke of the Libertines, sold as real-deal youth culture despite all evidence to the contrary. It’s everyone’s loss. Grime sounds new, hungry, not nearly close to being fully explored—and like it’s just getting started.