“I don’t know,” says No Depression‘s co-founder and co-editor Grant Alden, after a moment’s thought. “I don’t know whether it’s a case of ‘They said it wouldn’t last.’ I don’t think anybody noticed at first. Anyway, Peter and I were doing this for funwe never dreamed it would last so long. It seemed to be a step we could take affordably, and if it didn’t work out . . . at least we had fun and got to do something we wanted.”

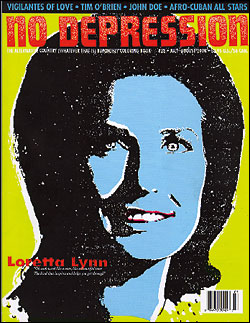

It’s been nearly eight years since Grant Alden and Peter Blackstock printed up the first 2,000 copies of No Depression “the alt-country (whatever that is) bimonthly,” as the magazine’s running tagline now puts it. In those days, it was a quarterly, and the total page count hovered around 32 and the pictures were photocopied and the first contributors got paid in T-shirts.

No Depression‘s inaugural run, though professionally printed, was pasted up and run off at a neighborhood Kinko’s.

How times do change.

From the earliest rumblings to the first printing, it took no more than five months for issue No. 1 of No Depression to come together. In April 1995, Alden had left The Rocket, the Seattle-based music magazine for which he’d served as managing editor, and was trying to make a go of a small art gallery. Blackstock, a writer and copy editor who’d written for Alden for some years, was keen on what had come to be called alternative country. A series of conversations”We double-dared each other,” Alden deadpansresulted in their decision to found an alternative-country publication.

“I think the focus on alternative country came mostly from me,” Blackstock says, “because that was something I’d been somewhat immersed in, growing up in Austin. I was probably a little more into it than Grant, though we overlap on these things in most every way. For Grant’s part, I think he was tired of documenting the whole grunge thingthis was the early, mid-1990s in Seattle, remember, and Grant had written a lot about that.”

No Depression touchstone Uncle Tupelo photo: Daniel Corrigan No Depression touchstone Uncle Tupelo photo: Daniel Corrigan |

The AOL alternative-country discussion board called “No Depression”initially centered upon the band Uncle Tupelo and named for UT’s cover of the Carter Family songprovided the title. Furthermore, that discussion board made Alden and Blackstock wonder whether there was already a readership in place for a magazine like the one they were considering.

“In a way, the potential audience was somewhat visible through the Internet,” says Blackstock, “and Americana radio was in its infancy then. We felt there might be an audience.”

“But from the earliest discussions,” Alden says, “we knew we were going to have to sell this to people. We were going to have to, first, show them that this music existed, and second, get them interested enough to read a magazine about it. If you look at the things they tell you in publishing school, that’s completely ass-backwards. You’re supposed to market to a ready-made audience. We didn’t do that.”

To compound matters, of course, there was no ready-made audience for alt-country/Americana/roots music or what have you, in 1995. There were only isolated bands like Uncle Tupelo and the Cowboy Junkies, singer-songwriters like Robbie Fulks and Terry Allen . . . and their scattered listeners, most of whom tended to fly beneath mainstream radar. (While working the grunge beat at The Rocket, Alden was wont to play Fulks’ “She Took a Lot of Pills [and Died]” at a publicly disruptive volume: “It made me feel better about the job.”)

“So we wanted very much to be nationwide from the beginning,” Blackstock continues. “And I think it paid off. For instance, early on we were based out of Seattle, but the two markets that really embraced us immediately were Chicago and North Carolina. In other words, we were pretty sure there’d be a readership for it, but not if we stayed local. We turned out to be right about that.”

Blackstock is now in Durham, N.C., and Alden is in Nashville, while business operations remain in Seattle.

Over the years, and to the consternation of some of the magazine’s more orthodox readers, No Depression‘s net has expanded to include neo-traditional country artists as well as young punks and outlaws. In recent issues, artists like Lee Ann Womack, Alison Krauss, and (accompanied by a cover shot destined to become a classic) Johnny Cash have all come within the magazine’s scope without dominating its pages.

“That wasn’t an area we visualized when we started the magazine, but it became clear that it was an area we had to explore,” says Blackstock. “The initial focus was on younger rock bands who were drawing from country or Americana. We quickly came to realize, and it quickly came to develop, that there was this subset of older traditional country artists who fit exactly into what we were doing, andmaybe more specificallydid not fit into what country radio was about anymore. One of the first letters to the editor we ever got was from a guy who wrote, ‘Finally, somebody who realizes Merle Haggard and Son Volt belong in the same magazine.’ It was a sign that there were these two seemingly separate avenues coming together in what we were doing.

Calexico photo: Daniel Corrigan Calexico photo: Daniel Corrigan |

“And we’ve taken some flak for that. But one thing we’ve come to discover is that, by and large, the people who seek us out and subscribe to us aren’t casual listeners. They’re serious music fans.”

Kyla fairchild joined Blackstock and Alden for the second issue of No Depression and currently serves as the magazine’s distribution and advertising director. Fairchild can quote chapter and verse, circulation and subscription, on No Depression‘s growth over the past eight years, and the numbers are impressive9,300 subscribers, 30,000 distribution per issue. And Fairchild was there four years ago, when the possibility of doing a regular radio show first came up.

“Everything develops,” she says. “You can’t publish for eight years and remain the same thing you were when it started. Not if you’re growing or wanting to grow. And we thought it would be a good idea to take what we were doing to mainstream radio and break this music in markets where it might otherwise never have gotten played.”

Ann Arbor-based Rob Reinhart, a 26-year radio veteran who’s produced the syndicated Acoustic Cafe show for over a decade, was called in to assist.

“At first, I did everything I could to show them how it could be done, while still keeping myself out of it,” Reinhart says. “But even after it was decided that I should script and voice the show, it took a year to get it off the ground. There were demos, rewrites, other demos, and it kept going back and forth until we first broadcast in April 2002.”

Like the magazine, the No Depression show is a family affair; Reinhart selects an initial playlist, which is checked and revised (minimally) by Blackstock and Alden, after which the script is written and the two-hour weekly show is taped, packed, and shipped to 36 markets around the continental U.S. (The program airs in Seattle on KYCW-AM, 1090. A complete list of the carrying stations and broadcast times is available at www.nodepression.net/radio.) Less Westwood One than American Songwriters 101, the show is a genial combination of entertainment and historical rescue, drawing links between old and new artists, writers, and performers. And, as its founders attest, it’s intended as a curative.

“The radio show is intended to give country radio plausible deniability,” says Alden. “It’s a chance for their audiences to hear older country music, which they might not be able to hear on that station, and for the stations to be able to program it in. And it allows their listeners to hear new artists who either won’t get a break on country radio or really don’t belong on country radio: Calexico, for example. We do a lot to promote songwriters, like we’ve always done with the magazines, and some people are surprised to find how major-name acts can fit into that. The Dixie Chicks are a perfect example. They made a really good record, and they’ve chosen great songwriters, which gives us a chance to play other songs by those writers and say, sort of implicitly, ‘Now, don’t be afraid, the Dixie Chicks have vouched for this.'”

Vince Gill photo: Andrew Eccles Vince Gill photo: Andrew Eccles |

“One of the resistance points we’ve been getting from stations is, ‘It’s too unfamiliar,'” Reinhart agrees. “So we’re making a very concerted attempt to expose an audience to this stuff who may not know about it. We’re just trying to give them a palatable way to bring this stuff to their listeners and to show them that it’s not that far away from what they’re doing already. The show isn’t all about regional alt-country bands who are hip in three states. It’s also about Vince Gill, who has a history, and who’s a very talented guy. And Lou Harrison, and Nanci Griffith, and Guy Clark. And the list goes on.”

The show’s early success is, perhaps, a sign that the mainstream is finally taking some notice of the music No Depression has chronicled for (come September) eight years. “I’d like us to be on in Nashville,” says Reinhart. “And maybe one more top-10 market. That’d be cool.”

But No Depression‘s always had a semisubversive edge to it; its ability to remain niche-oriented without becoming a parody of its former self is a testimony to the people who run it, but also indicative of itsand the music’spassionate fan base.

“I like to say we’re corrupting people, one at a time, all over the world,” says Alden. “One thing that’s been lost in America and in the world in some ways is our ability to have and sustain local communities. When our magazine works, it provides connective tissue for a sort of community. And I hope, in the end, it’s a fair and important part of that community.”