This story was originally published on November 2, 1994, under the title “Battle of the Band.” It is being resurfaced as part of the Weekly Classics series.

The office of Curtis Management is an unlikely setting for corporate intrigue. A picturesquely seedy second-floor walkup above the Puppy Club at Fifth and Denny, it resembles a private detective’s office in an old B movie. Its floors are slanted, its door crooked, its walls grimy. It is furnished mostly with second-hand stuff: old desks, overstuffed chairs, a couch. … Cluttered with magazines, piles of paper, and discarded food containers, it is peopled by youngsters in torn clothes, with haircuts that look like found-art projects.

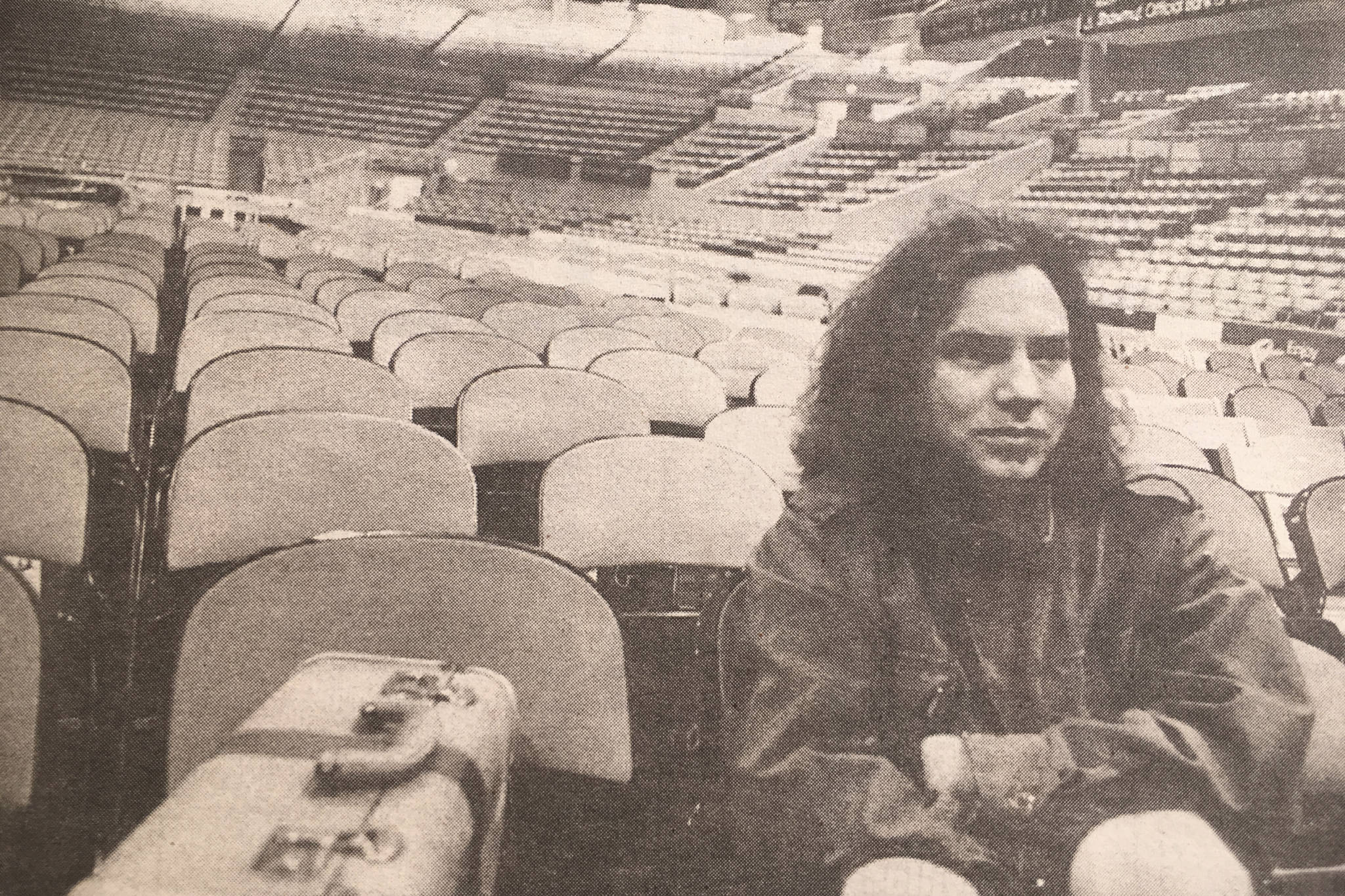

Kelly Curtis, a chain-smoking young man who generally wears jeans, T-shirts, and baseball caps to work, presides over this grungy milieu, holding court and asphyxiating guests in an office with a smashed electric guitar hanging on one wall. Manager of Seattle’s Pearl Jam, currently the most popular rock act in the world, Curtis at the moment is more or less single-handedly trying to turn back the tide of greed that has forever been sweeping over the live-entertainment industry. To that end, he has taken on Ticketmaster, the vendor that sells tickets to virtually every live event in the nation, whether in small clubs, large concert halls, or athletic arenas and stadiums.

Just as Curtis and his band should have been joining hands with Ticketmaster to rake in a lion’s share of the gross income from America’s $1 billion-a-year industry, Curtis instead finds himself at war with the ticketing giant, and Pearl Jam finds itself pretty much out of work. The story of how that rather bizarre state of affairs came about, and where those involved in it are headed next, is both tangled and morally complicated.

The story is also that of a battle over tremendously high stakes. Pearl Jam’s canceled tour probably cost the band more than $3 million. And while Ticketmaster won the first battle against the band by forcing the cancellation, its victory may prove to be pyrrhic. The dispute has occasioned a congressional investigation of the company, another investigation by the Justice Department, and a spate of bad press from which Ticketmaster may never recover. A company that started out 16 years. ago as an innovative, moral force correcting hideous abuses and inefficiencies in the live-event ticket business is now being portrayed as one of the most corrupt and abusive companies in rock music. Should Pearl Jam prevail in the public-relations war, Ticketmaster could fall victim to a combination of federal regulation and consumer backlash daunting enough to put the company out of business.

Seattle’s “alternative rock” bands, of which Pearl Jam is the most popular, are an anomaly in rock music. They eschew most of the trappings and perks of stardom, including the stratospheric sums of money that rock stars command. The alternative-rock scene in which they perfected their acts was a movement that rose up in response to the bloat abuse and corruption that so characterizes the world of mainstream rock ’n’ roll. Alternative bands around the country, signing with local managers, performing in local clubs, and recording with a local record label (in Seattle’s case, Sub Pop), sought to bypass the corporate rock world, in which musicians are forced into unpalatable aesthetic compromises for the sake of gaining access to a mass market and generating massive sums of money—most of which goes into the pockets of “the men in suits,” as rock’s business people are called. That present-day alternative rock better-sustained itself than anti-commercial movements of the past is largely due to advances in technology that made it possible for small operations, like Sub Pop to record, produce, and distribute decent recordings on compact disc.

In many respects, alternative rock was an attempt by artists to regain control both over their music and over the business of delivering it to an audience. As has been well-documented in two highly regarded books on the rock-music industry, Frederic Dannen’s Hit Men and Marc Eliot’s Rockonomics, the pop music world has long been rife with both artistic and corporate corruption, with the result that music is, poorer, records and concerts are more expensive, and artists are often cheated out of most of the money they earn. The late Frank Zappa founded his own record label in an attempt to keep corporate rock from forcing compromises into his work, and bands have forever complained about the cunning with which the men in suits cook concert-tour books to make it appear that there is no money left over after production expenses to pay the touring band. (The 1970s were particularly notorious for tours that made money for everyone except the performers.) Alternative rock sought to deliver directly to audiences music undiluted by corporate greed and marketing, and to eliminate the excessive profiteering by large companies off of the life’s work of musicians.

The surprising explosion of grunge on the international stage, and its attendant corporate co-optation, brought to alternative bands more trauma than satisfaction. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain committed suicide; Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, given to growling sarcastically about his band’s celebrity, grew progressively more surly and drunk at performances; and now Pearl Jam has dropped out of the conventional concert-tour industry altogether.

Back in their salad days, in accord with grunge tenets, Pearl Jam’s members resolved to keep their concert-ticket prices low should the band ever hit it big. Now, in a business whose most popular acts brings in upwards of $30 per ticket (the Eagles, for example, recently sold out two Tacoma Dome concerts at $45, $60, and $85 per ticket), Pearl Jam wants to charge $18. The band also wants vendors of T-shirts and other souvenirs, and the brokers who issue tickets, to charge less for their wares and services, so that kids can attend one of their concerts for $20 and still be able to by souvenirs and refreshments.

Pearl Jam’s peculiar ethic first brought it at odds with Ticketmaster, which controls at least 90 percent of the American ticket market, during the 1992 Labor Day weekend, when the band staged two free concerts for Seattle fans. Ticketmaster wanted to assess a $1 service charge for each free ticket it issued. The band balked and eventually distributed the tickets itself. On its subsequent 1993 40-city tour, Pearl Jam lowered its ticket price to $18—over objections of concert promoters who urged the band to charge up to three times that amount—and negotiated lower commissions from T-shirt and souvenir vendors. The result, in the case of T-shirts, was a price lowered from $23 to $18. Promoters estimate the total loss to the band in ticket and merchandise revenue for the ’93 tour alone around $2 million.

When it came time to tour again this spring, Pearl Jam drew an even harder line as it began lining up a 24-date series of appearances. In addition to its previous strictures, the band declared that it would appear only at venues where its tickets were priced at $18, ticket-distributor service charges were $1.80 or less, and the tickets would have no advertisements printed on them. (Ticketmaster routinely sells display-ad space on its tickets and pockets the revenue.)

According to manager Curtis, the band objected to Ticketmaster’s service charges on two grounds. Ranging from $4 to $8 from venue to venue for the same $18 ticket, the charges clearly bore no relationship to the ticket price, and appeared to have no relationship to the service provided. And even at their lowest level, the service charges seemed unreasonably high. In the band’s view, Ticketmaster was taking unfair advantage of adolescent passion and unreason in a marketplace where there was no competition.

“They thought $4 was too much for an $18 ticket,” Curtis recalls. “It doesn’t cost them any more to print a concert ticket than a circus ticket.” It seemed to him that the service charge should be based on the actual cost of the service provided and that therefore should not vary so much from event to event, or city to city. Although initially wanting to hold the line at $1.80, Curtis was willing to give a little in negotiations With the ticket broker. “We would have settled for $2.25,” he says.

While Ticketmaster will not comment directly on negotiations with Pearl Jam, one industry source with ties to Ticketmaster CEO Fred Rosen claims that Rosen would have settled for $2.25 as well; but that Curtis and Pearl Jam refused to budge. Curtis says that by the time Ticketmaster came down to the $2.25 level, “It was too late.”

Deciding that differences between the two were irreconcilable, Pearl Jam opted to tour without using Ticketmaster for any of its concerts. The band went looking for alternative ticket distribution companies, reasoning that they should be able to choose from among several ticket vendors just as they do among several promoters, booking agents, venues, T-shirt companies, and so on. The band started out with a New York concert for which it sold tickets through radio stations, and a Detroit-area concert where it sold tickets through a lottery.

There were difficulties in Detroit. Ticketmaster threatened to sue the concert promoter, the Nederlander Organization, for violating its contract with the ticket vendor by trying to sell tickets through someone other than Ticketmaster. Then Ticketmaster shut off its ticket machines at the concert venue, rendering it impossible to print up tickets. Pearl Jam claims in a memorandum filed last May with the Justice Department that the company turned the machines back on at the last minute, only after it was clear that the band would not back down.

After Detroit, Pearl Jam ran into an insurmountable obstacle: it could not book arenas anywhere else in the country. Ticketmaster, which has inked “exclusive contracts” either with arenas or concert promoters in every major American city, threatened to enforce the contracts if any of the signees tried staging a Pearl Jam concert without using Ticketmaster. Promoters received a memo from North American Concert Promoters Association executive director Ben Liss, stating, “Pearl Jam is putting out feelers once again to require promoters to bypass Ticketmaster on their dates later this summer. TM has indicated to me they will aggressively enforce their contracts with promoters and facilities.” A day later, Liss sent out a more explicit missive: “Fred [Rosen] has indicated that he intends to take a very strong stand on this issue to protect Ticketmaster’s existing contracts with promoters and facilities and, further, TM will use all available remedies to protect itself from outside third parties that attempt to interfere with those existing contracts. … If asked, you may wish to consider and cite this fact: you and/or your venue have an existing contract with TM which precludes you from contracting with others to distribute tickets. I urge you to be very careful about entering into a conflicting agreement which could expose you to a lawsuit.”

These exclusive contracts contain two interesting provisions—one of which helps explain the variety and high levels of Ticketmaster service charges. Arenas or promoters who sign them are prohibited from allowing anyone else to sell their tickets; and Ticketmaster “rebates” or, in the words of its critics, “kicks back” some of the service charges to its contractors. Venues that have entered into such agreements with Ticketmaster are reported to have taken in as much as $500,000 per year from the ticketer as a result—payment, essentially, for freezing competitors out of the market.

In the Seattle market, the contract system serves Ticketmaster well. The company pays the Tacoma Dome—the area’s leading rock venue—$450,000 per year, in advance, for the right to be its exclusive ticket vendor. Since no rock promoter can survive in the Seattle market without access to the Tacoma Dome, Ticketmaster ensures by means of its exclusive contract that only Ticketmaster-friendly promoters can do business in the Seattle market. This tactic has been an integral part of Ticketmaster’s strategy nationwide. “The agency that wins over the major facility in a midsize city,” wrote David Koss and Matthew Walker of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union in a complaint about Ticketmaster to the Justice Department in 1991, “typically succeeds in establishing market power over that geographic market.”

In addition to locking up those venues, Ticketmaster also signs contracts directly with promoters. So even a venue that refused to contract with Ticketmaster finds it impossible to stage a non-Ticketmaster concert, as any viable promoter in a given market will also have an exclusive contract with Ticketmaster. The Seattle Center, for instance, which does not have an exclusive contract with Ticketmaster, cannot find a promoter who is not under contract with the company, so the Center’s refusal is essentially meaningless. (Pearl Jam was able to distribute its own tickets for its free concerts at the Center in part because the band did not employ a promoter.)

The combination of exclusive contracts—with all local promoters and with the Seattle market’s prime concert facility—ensures that non-Ticketmasters from out of town cannot come into town and establish a presence. A promoter who is locked out of the Tacoma Dome cannot survive in Seattle. As Dave Leiken, of Portland’s Double T Promotions (a company that refuses to sign exclusives with Ticketmaster partly because Leichen also owns a competing ticket company, Fastixx), puts it, “The Tacoma Dome’s exclusive keeps us out of the Seattle market. Ticketmaster establishes these connections, creates monopolies, and creates an unlevel playing field to help their friends”—promoters under contract to them.

Because of Ticketmaster’s avowed determination to enforce its contracts by suing promoters who cooperated with Pearl Jam, says Kelly Curtis, “We realized that we couldn’t put together a safe, efficient tour without using existing venues. In order to do that, we would have to use non-Ticketmaster venues, which means open fields where we install fences, security, amenities. … It was a logistics thing. It’s possible to do a tour without Ticketmaster, but it’s an incredible pain in the ass.”

The group cancelled its ’94 tour and is now putting together one for next summer, to be undertaken with neither the services of Ticketmaster nor the threat of a Ticketmaster lawsuit against promoters. Outdoor venues, Curtis says, will be built “from the ground up” without the assistance of Ticketmaster-contracted promoters.

Pearl Jam also filed its complaint with the Justice Department, and two of its members—Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard—testified last June before the House Information, Justice, Transportation, and Agriculture Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, chaired by California Congressman Gary Condit, which is mulling over a bill requiring that service charges be itemized and printed on tickets. Gossard and Ament claimed that Ticketmaster operates a monopoly allowing it to dictate terms to everyone with whom it deals, to eliminate all competition, and to put out of business any performer who tries to put on concerts without involving Ticketmaster. It attests to the power of Ticketmaster, and to the degree to which people resent the company, that Pearl Jam has been praised throughout the performance-and-promotion industry for being exceptionally “courageous.” After testifying against Ticketmaster before the same subcommittee, Aerosmith manager Tim Collins said in an interview with Billboard that he had no choice but to use the company, even though he hated doing so. Nor, he said, could his band have dared take’ on Ticketmaster by itself. “We weren’t in a position of not touring,” he said. “I mean, how many years does Aerosmith have left?” Added Chuck Morris, manager of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, “Pearl Jam’s attempts to bring this problem to the forefront are extremely admirable.”

Fred Rosen vigorously denied all charges in his testimony, claiming that Ticketmaster makes only 10 cents in profit off each transaction, and nets only $14 million in after-tax profits on $172 million in annual revenues. Subcommittee staffers insist that the profit figures must be artificially low, given that Seattle billionaire Paul Allen was willing to pay $300 million for 79 percent of the company. “You don’t pay that much,” said one staffer who asked not to be identified, “for a company that makes so little money.” Allen, through a spokesperson at Vulcan Northwest, his Bellevue-based investment company, declined comment.

To make its case to the press, Ticketmaster has engaged public-relations expert Larry Solters from Spin Media in Los Angeles. Solters is a forceful and colorful speaker who affects epic outrage at Pearl Jam’s charges. With bracing cynicism, he dismisses the band’s effort as “a brilliant marketing ploy.” He claims that. “the bands bitch about service charges because they don’t get the money,” and that they don’t appreciate Ticketmaster’s success in “broadening their fan base.” Ticketmaster has grown into such a big and powerful company, he says, only because demand insisted upon it. “We’re depicted as the Goliath,” he says, “but the business has grown because fans demand our service.”

When it comes to the particulars of Pearl Jam’s “accusations, Solters doesn’t even wait for his interviewer to cite them before he begins his rebuttal. He insists that there are”“hundreds” bf competing ticket companies, and that arenas choose Ticketmaster simply because it’s the best in the business. Ticketmaster is not a monopoly, he says further, because fans can always bypass the company by buying tickets at a box office. If they opt to buy them through Ticketmaster, they pay, by choice, for the convenience.

“People ” confuse Ticketmaster with a box office,” he says. “But that alternative is always there. You pay for the delivery service—it’s a delivery service, not a box office. Nobody’s putting a gun to anybody’s head—if you don’t want to use us, don’t.”

Solters is particularly angry at Pearl Jam for claiming that Ticketmaster made it impossible for them to tour. “Nobody prevented them from touring!” he shrieks. “They could’ve told people not to use us.” Then he adds, cryptically, “They wanted to move into someone else’s house and rearrange the furniture.”

Pearl Jam manager Curtis, daunted by the slick ferocity of Solters’ debating style, no longer bothers to respond to the spokesman’s claims. “I’m kind of bummed with the way all this turned out, to tell you the truth,” he says, stung in particular by Solters’ insistence that Pearl Jam’s crusade is a simple publicity stunt.

While they contain kernels of truth, Solter’s claims of aggrievement and innocence look disingenuous at best when considered in light of the actual history and practices of Ticketmaster. It is true, for example, that Ticketmaster did not directly “prevent” Pearl Jam from touring. As the North American Concert Promoters Association memos show, however, Ticketmaster turned a Pearl Jam tour into a practical impossibility. In essence, concert promoters and arena managers across the country, by virtue of their exclusive contracts with Ticketmaster, had forever traded away the right for themselves and their performers to choose a ticket vendor. In return, the promoters and arenas are paid handsomely by Ticketmaster, which turns around and recoups its rebate costs by exacting higher “service charges” from ticket buyers.

Ticketmaster rebuts that last claim by claiming that its average service charge has increased only 46 cents over the 1990-1993 time period, from $2.69 to $3.15. The company’s critics point out, however, that the average is skewed by the vast number of small events, with low ticket prices, that Ticketmaster handles. (The figure is also skewed by contracts like the one Ticketmaster has with the Seattle Mariners, which calls for Mariners fans to pay only a small service charge, but which also calls for the Mariners to rebate to Ticketmaster a percentage of the ticket price. Looking just at rock concerts—the leading money-maker for Ticketmaster, accounting for 55 percent of its business—you find service charges as high as $10.50, and sometimes as high as 55 percent of a ticket’s face value.

Other facets of Solters’ spiel are similarly “true.” The box-office alternative, for example, is for all practical purposes nonexistent. A consumer hoping to attend a concert generally cannot buy a ticket at a box office until the day of the event, by which time the event has long-since been sold out, through Ticketmaster. So the buyer has no choice but to pay for the “convenience” of actually being able to purchase a ticket. Solters’ feverish, “If you don’t want to use us, don’t,” could more accurately be stated, “If you don’t want to use us, don’t attend the concert.”

As for competition: There are indeed other ticketing companies operating in the United States. But the history of Ticketmaster is a history of it driving all of its competitors either out of business or into smaller niche markets—largely by means of rebate-driven exclusive contracts. It is a history of which Fred Rosen is said to be particularly proud. “He loves to gloat about the people he’s driven under,” says one local concert-industry figure. “I’ve been in meetings where he sits there and says, ‘I drove so-an-so out of business … I put this guy out of business.”

The latest installment in the ongoing history of Ticketmaster’s aggressiveness is the undercutting of MovieFone, a company that sells movie tickets over the telephone in various American cities, and that has as its partner a hardware/software company called Pacer-CATS, which handles the actual ticketing inventory and delivery. (Seattle Weekly recently contracted with MovieFone to provide free movie times to its readers). MovieFone was surprised recently to discover that Ticketmaster bought a majority interest in Pacer-CATS just as MovieFone was mulling over the move into ticketing live events for a blanket $1 service charge. So Ticketmaster effectively drove MovieFone out of live-event ticketing, according to MovieFone’s congressional testimony, before the newcomer could get started. MovieFone, fearing that Ticketmaster also intends to move into movie-theater ticketing (Ticketmaster has experimental movie-ticketing services under way in Dallas and Los Angeles), alerted the Justice Department of the Pacer-CATS purchase this past September. (While it was completing its purchase of Pacer-CAT‘S, Ticketmaster was testifying before Congress that MovieFone was one of its competitors rather than a reluctant partner-in-the-making.)

Before considering Ticketmaster’s earlier history, it is instructive to look at what exactly it provides consumers and event managers, for the Ticketmaster service is undeniably impressive—and undeniably popular, its high cost to consumers notwithstanding. On any given day in Seattle, a consumer can call Ticketmaster and purchase tickets to any of more than 600 events, from a small club performance that night to a baseball game three months away. On a single Tuesday night in Seattle recently, there were 16 Ticketmaster-brokered events going on in Seattle.

The Ticketmaster operator taking a caller’s order can summon on his or her terminal the number and location of seats available for the performance or event of interest to the caller, the price of the tickets and their service charge, and information on such things as parking, concessions, the length of the intermission, and directions to the venue.

While the convenience factor Ticketmaster affords cannot be overemphasized, neither can the value of the information it provides. One of the prime justifications for the company’s high service charge is the fact that only one of eight callers actually buys a ticket; the rest call for information and pay nothing. The company is an information source for nearly every live event in the region. “Seventy to eighty percent of our calls,” says Ticketmaster Northwest general manager Brian Kabatznick, “are for information only and generate no revenue.”

No one who remembers Seattle’s pre-Ticketmaster days can forget the chaos and confusion that would attend the release to the market of tickets to popular acts. Lines would form outside such places as Fidelity Lane or various record stores in advance of high-profile rock concerts, and it was not uncommon for fights to break out, or for fans to wait overnight at a given ticket outlet only to discover that that outlet had been allotted no tickets to choice seats.

By comparison, concertgoers now can call a single number for every event in the local universe, and have accessible at someone’s (admittedly pricey) fingertips nearly all the information they need on a given event. Ticketmaster also gives its clients—the promoter or venue manager—up-to-the-minute information on his or her ticket inventory. When a ticket to a Seattle event is sold through a Ticketmaster outlet in Spokane or Boise, every computer terminal in the company’s system is immediately apprised of the sale. Every ticket to every seat in a given venue is available simultaneously at every one of Ticketmaster Northwest’s 110 outlets, or through its telephone operators, or at the venue’s own box office.

As a result, massive sales can be undertaken and completed almost instantly. When tickets for the December 15 Seattle stop of the current Rolling Stones tour went on sale here, Ticketmaster sold 5,000 tickets in the first five minutes, and 25,000 in the first hour—“All,” says Kabatznick, “without incident.”

In the current climate of outrage surrounding the Ticketmaster debate, three important facts are forgotten: one is that tickets, once left in the control of promoters and other dubious characters on the fringe of the concert industry, often passed through clandestine channels, where the choicest tickets were siphoned off by scalpers and marked up three or four times before finally reaching the consumer. Tickets to the best seats at the most popular events frequently sold for anywhere from five to ten times face value, with none of the mark-up money making its way into the pockets of performers. Ticketmaster eliminated many of these abuses with a computerized ticketing system that put all tickets on sale everywhere simultaneously. Although some choice seats are still held back for promoters and record-company executives, and some are still marked up and resold by professional scalpers, the bulk of them are sold directly to consumers, and limits on the number of tickets individuals can purchase at a Ticketmaster outlet have cut back dramatically on scalping (albeit, insists Pearl Jam manager Kelly Curtis, not-totally, and not enough).

It is also forgotten that Ticketmaster rose to dominance at the expense of an established, competing company—Ticketron—that operated a virtual monopoly in the early 1980s, and that was notorious both for insensitivity to customer complaints and for its refusal to innovate or increase efficiency. Ticketron was so bad that many venues opted for non-computerized ticketing rather than Ticketron’s computerized service. Even Curtis says that Ticketmaster succeeded because “they are good, smart businessmen. They were way better than everyone else—Ticketron just wasn’t as good.”

Finally, there is the invaluable service Ticketmaster provides its clients—the promoters and venue managers who contract with the company. Ticketmaster outfits the box office of a client venue with hardware and software, maintains it, in some cases staffs it, and provides inventory control and data on customers that venues and promoters can use not only for ticket sales, but for targeted direct-mail campaigns. And even those who complain loudest about Ticketmaster’s monopoly are quick to praise Kabatznick’s Seattle franchise for its superb service, and to distinguish his behavior from that of Fred Rosen, who makes and enforces Ticketmaster’s contracts. “Brian’s a good guy,” says one manager who declines to be identified. “He just works for an asshole.”

Ticketmaster, founded by two Arizona State University computer students in 1978, got its first big break in 1981, when it was a struggling $1 million-per-year upstart trying to take on $100-million-per-year giant Ticketron. Ticketmaster needed a major client to give it credibility, and to prove that the company could handle a large account and a complicated set of ticketing problems efficiently. They also wanted a client with a national profile. It settled on a major-league baseball franchise whose new owner was appalled to find that his team did not have computerized ticketing. At the beginning of each baseball season, tickets to every seat for every game were printed, stored somewhere in its stadium, then delivered to box offices and ticket outlets as game dates approached. The system was horribly inefficient, and wasteful as well, as most of the tickets printed up were never sold.

The team was the Seattle Mariners, and the owner was George Argyros. Ticketmaster sold Argyros a 50 percent interest in a new Seattle Ticketmaster franchise, now called Ticketmaster Northwest, in return for becoming the Mariners’ ticket vendor. Ticketmaster took over the Mariners ticketing operation and parlayed its success in Seattle into a national reputation that led eventually to its takeover of the American ticketing industry. By the end of 1990, Ticketmaster had nearly twice as many outlets across the country as Ticketron did, and had $500 million in sales as compared with Ticketron’s $500 million. And Ticketron was fading fast: in 1991, Ticketmaster bought its rival, in a deal approved by the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division—and second-guessed ever since.

Another critical factor in Ticketmaster’s success was the arrival of Fred Rosen in 1982. It was Rosen who introduced the practice of raising service charges so as to have enough left over to pay percentages to promoters and venues. In bidding against Ticketron, Ticketmaster not only offered better service, but far better terms: promoters choosing between the two were choosing between a bidder who was

promising to pay them for a contract and a bidder who was not. While the consumer would undeniably benefit from paying smaller service charges, promoters and venue managers—those who awarded the contracts—quite obviously would not. Small wonder that they opted for the less consumer-friendly bidder.

The problem now, of course, is that there is no one left to bid against Ticketmaster. It’s one thing to beat out your competition; it’s quite another to eliminate all competition forever. The question before Congress and the Justice Department at the moment is over which of those two statements best characterizes Ticketmaster. Just how bad are these guys, anyway?

Given the history of the music business, Ticketmaster is relatively benign. The practice of kicking service-charge money back to promoters, for example, looks less sleazy When you consider that tickets historically have been the property of promoters. In rebating service charges to promoters, Ticketmaster is simply giving them a share of what historically has been theirs anyway. And promoters have been driven into the arms of Ticketmaster by another development in the economic history of rock: by the end of the 1970s, the top rock bands, justifiably outraged at industry practices that cheated them out of virtually all of the income generated by their tour appearances, began refusing to appear unless they were guaranteed 90 percent of the face value of tickets sold for their performances. Promoters and venue managers saw their profit margins reduced to almost nothing, and began looking for alternative revenue streams to make up the difference. Thus the prices of souvenirs and refreshments were driven higher and the ticket Service charge emerged as a new, particularly productive revenue stream.

It should also be borne in mind that the music industry has always, for whatever reason, been held to a different standard from the rest of American business. “Conflicts of interest that would scandalize most businesses,” writes Frederic Dannen in Hit Men, “are commonplace in the music field.”

Local music industry figures, while professing sympathy and admiration for Pearl Jam, are also careful not to heap abuse on Ticketmaster. Some clearly do so out of fear of the company, but others recognize that the Ticketmaster question is more complicated than it appears to be. One local promoter doesn’t want to comment because “Kelly and Brian are two of my best friends.” Mariner president Chuck Armstrong (who also, for the record, sits on the board of Ticketmaster Northwest) feels that Ticketmaster should be entitled to a degree of freedom from competition because the company invests so heavily in hardware, software, and service. How could Ticketmaster be expected to outfit the Kingdome box offices with a computer system, he asks, if they can’t be assured of keeping the Mariners as a client for years to come.

Most vociferous in his defense of Ticketmaster is Jim Weyermann, deputy director of Seattle Center—even though he has never signed an exclusive contract with the ticketer. Weyermann insists that the company is less “greedy” than most other music industry participants. “To single Ticketmaster out is completely unreasonable,” he says. “They’re a part of a complicated equation. Who do you want to take less from consumers? You have the bands, the promoter, the building, the merchandising, and the ticketer all taking money. One of the five has to take less in order for the consumer to pay less. Why should it be the ticketer. If someone is willing to pay $85 for an Eagles ticket, how likely are they to complain about a $6 service charge.”

Weyermann goes on to point out, though, that “the alternative bands are different,” for they are willing to take far less money. Pearl Jam, for example, sacrificed millions by cutting its ticket prices by as much as 66 percent. In asking that the other four parts of their concert equation to follow suit, they were asking no one to do what they were unwilling to do. The only people who refused were the people at Ticketmaster whose unassailable power made them alone able to say “No.” And there is no denying that their power stemmed from a single circumstance: the fact that they operate what is effectively a monopoly.

Two other Northwest markets help highlight the difference to consumers between a monopolized market and a relatively open one. In Portland and Spokane, thriving—if small—competitors to Ticketmaster can be found. In Spokane, a company called G&B Select-A-Seat outbid Ticketmaster for the right to ticket all events held at City of Spokane-operated venues, which include an opera house, an arena, a convention center, and a few other sites. Spokane, which refuses to accept ticket-vendor rebates, awarded its contract to G&B because that company agreed to a service-charge ceiling of $1.50. And in Portland, city regulators require that all venues—including Paul Allen’s new sports-and-entertainment complex—accept competing bids for ticketing. As a result, Ticketmaster must compete against Fastixx, a local company, for all ticketing contracts. Fastixx holds its own against Ticketmaster, and services charges in Portland range from less than $1 to a maximum of $3.50 (Seattle’s average service charge, by contrast, hovers near $4.50).

There can be no question, then, that the presence of competition drives ticketing service charges down. Where Ticketmaster has no competition—which is nearly everywhere—service charges are immeasurably higher than in Portland and Spokane.

There is a question, though, of whether even that is relevant when it comes to antitrust law.

In its testimony before congress, Ticketmaster pointed out that its clients are venues and promoters rather than ticket buyers. Thus the problem for consumers is a fundamental flaw in the event industry than in the practices of a single vendor. The ticketer serves his fellow vendors rather than the ticket-buying customer. Promoters and venues choosing Ticketmaster are doing so because of the benefit to themselves rather than the benefit of the consumer. In such a skewed market, says a congressional subcommittee staffer who insists on anonymity, “the incentive is to raise the revenue stream rather than to hold prices down. As long as that incentive is there, the consumer gets fucked.”

This trenchant observation brings up the essential problem in nearly all antitrust investigations. Should the government protect consumes or other businesspeople from the practices of a powerful competitor? If the answer is that consumer protection should drive government, then Ticketmaster should be reined in. But if the answer is that other businesses—in this case arenas, concert halls, stadiums, and even promoters—deserve protection, then Ticketmaster should be left free to do what it does best.

There is also, of course, the question of whether the price of Ticketmaster’s largess is unreasonably high and anti-competitive. When a contract effectively freezes out all competition for a promoter’s business forever, it is hard to argue that a business can enjoy the power Ticketmaster enjoys and still comply with antitrust laws.

The Pearl Jam contretemps vividly demonstrates what effect the Ticketmaster monopoly can have on other music-industry businesses. Ticketmaster’s power is such that it can keep the most popular band in the world off the national stage just because the band wants to use a different ticket vendor. Thus Ticketmaster is guilty, in the eyes of one congressional staffer, of one of the most obvious monopolistic abuses of power in American history. “This is a ticket cartel,” he says, alluding to the early days of Standard Oil, “that rivals Rockefeller.”

If the federal government’s attempts to deal with antitrust issues is any indication, though, there is no such think as an open-and-shut case in antitrust law. Far larger enterprises—IBM, AT&T, Microsoft, and major-league baseball come most immediately to mind—have either won antitrust cases outright against the federal government or kept the feds tied up for years trying to break up their alleged monopolies.

Ticketmaster, like IBM before it, is more likely to falter or decline because of changing market conditions than because of federal intervention. Knowledgeable sources claim that the availability and ease of use of current computing technology has so lowered the barriers of entry into the ticketing market that competitors inevitably will find a way to break Ticketmaster’s stranglehold. And if Pearl Jam pulls off its concert tour next year, a template of sorts will be in place for other acts to follow. The history of monopoly in this country, after all, is more a history of disgruntled competitors and customers finding an alternative to the services of a monopolist than it is a history of the government regulating monopolies out of existence.

Ultimately, the question of whether a monopoly can survive its own abuses of power boils down to how much consumers will tolerate. Companies that are morally monopolistic—even if not monopolists in the tangled and technical legal sense of the word—grow so cynical in the process of accumulating and keeping market power that they lose touch with reality, become incapable of decent public relations, and overstep some boundary in the consumer’s mind. Monopoly, in this sense, is like pornography—consumers can’t define it, but they know it when they see it. And ultimately they turn away from the monopolist in disgust.

In this connection, it is instructive to close with a final anecdote about Pearl Jam’s trip to Washington, D.C., to testify before Congress. “We had some time to kill,” Curtis recalls, “so we decided to go see the Holocaust Museum.” When they got to the museum door, Curtis, Gossard, and Ament discovered that they needed a ticket to get into the most interesting exhibits. Admission was free—but the service charge, levied by Ticketmaster, was $3.

news@seattleweekly.com