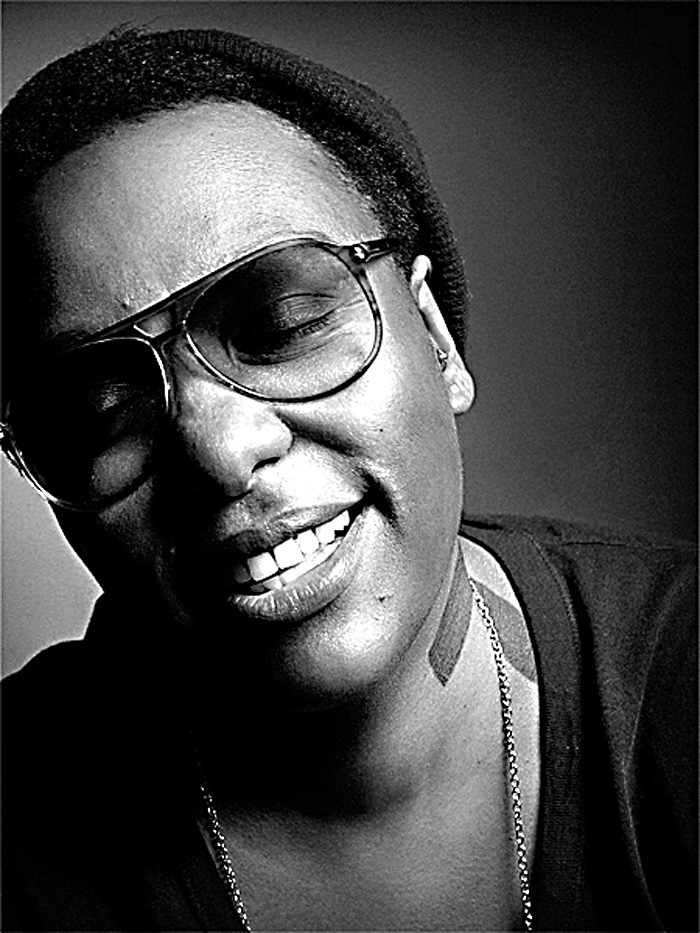

“If you could lick your balls,” chuckles Meshell Ndegeocello, “you would!” With that playfully indelicate visual, Ndegeocello illustrates a point she’s been making through music for the better part of her career: Spiritual growth need not preclude sensuality. In fact, as far as the renowned bassist/songwriter is concerned, they may as well be one and the same. Where Al Green and Prince have built careers on walking an inexplicably jagged line between sexual and religious themes, dichotomizing them to an absurd degree, Ndegeocello continues to make bedmates of God and desire. Throughout her work, the results of their union are often messy, but always insightful.

“I’ve never seen them as separate,” she explains. “Especially in heterosexual lovemaking, just the possibility that through that act, you can make another fucking human being…that’s some pretty God-like shit. Also, the fact that you want to make another person feel good, that’s pretty divine to me. That closeness, those exchanges of endorphins and hormones and chemicals, are an amazing way to bring people together, and hopefully it creates a bond that makes less violence.”

Ndegeocello sailed the cosmic vistas of that chemical exchange on her 2003 album, Comfort Woman, a buttermilk-smooth slice of futurist down-tempo soul that, with its breathlessly enamored lyrics and oceanic dub grooves, depicts attraction as blissful out-of-body transcendence. She’s in Seattle under the umbrella of the Earshot Jazz Festival, just weeks after the release of Devil’s Halo, which in some ways returns to the casual sound of Comfort Woman. Given Ndegeocello’s tendency to swerve wildly among styles from album to album, Halo‘s stripped-down, straight-ahead soul-rock sound and kinship with Comfort Woman (think of it as the latter’s troubled, spiky-haired adolescent cousin) comes as something of a surprise. Since 2003, for example, Ndegeocello has ventured into experimental jazz on the mostly instrumental 2005 album The Spirit Music Jamia: Dance of the Infidel, then followed that with the ambitious, hyper-eclectic sprawl of 2007’s The World Has Made Me the Man of My Dreams.

But if Devil’s Halo provides evidence that the bassist and songwriter is feeling less need to make sharp turns into new genres or invent new languages out of her vast range, her lyrical approach remains as direct as ever. Who could forget the taunting, mean-spirited homewrecker protagonist of “If That’s Your Boyfriend (He Wasn’t Last Night)” from her 1993 debut, Plantation Lullabies? Since then, Ndegeocello has kept her lyrical tongue sharp on matters of race, tolerance, homosexuality, and of course religion. Never one to shy away from bluntness, some of Ndegeocello’s religious imagery can make even the most secular listener blush. To name just two: the song “Leviticus: Faggot” from 1996’s Peace Beyond Passion, and the (eventually scrapped) album cover for 2002’s Cookie that depicts the openly gay Ndegeocello wearing a hijab. But beyond the sheer provocative daring of such juxtapositions, Ndegeocello has a knack for inverting sacred symbols to underscore her questions about other, more human issues.

The simple contradiction in the new album’s title announces the music as yet another foray into the spirit realm, but it also acts as a kind of keyhole view into the basic longings that dog us day to day. For all her fascination with religious iconography, Ndegeocello has never lost her grip on religion’s implications as a matter of the heart. As she returns to it again and again on Devil’s Halo, isolation—even more than the sexual charge the songs exude—serves as the linchpin that pushes her narrators to strive for connection in the first place. And whether that connection arrives in the form of God, another person, or both, in Ndegeocello’s music all forms of communion are eventually followed by a lingering sense of uncertainty.

“People really don’t know anything,” she offers. “With my friends that are really attached to religion and all the dogma of it, and feel that their way is the way and that they know it for themselves…I don’t use any of my consciousness to even try to understand or critique it. My love means we hang out, we eat, love our children, do things together…I have great empathy and understanding for everyone, and I hope they have it for me, but I’m not invested in their hope for me. That’s what I think it means to become an adult: Without God and the devil, I only have myself to blame.”