In April 1964, bluesman Walter “Furry” Lewis arrived home in Memphis after a tour only to find his house had been burglarized. The thieves took all Furry’s clothes (“two suits, five shirts, and two pairs of shoes”), and they even stole his groceries. Furry wrote about the incident in a letter, complaining they had “stole every thang.”

This simple letter, written in pencil and full of misspellings, is one of the many pieces of blues memorabilia in the Experience Music Project’s massive new exhibit “Sweet Home Chicago: Big City Blues, 1946-1966.” The straightforward missive documents a mishap only all too familiar to the traveling musician, and it hints at why this particular bluesman had the blues. It’s also an example of why EMP’s blues exhibit succeeds, where Martin Scorsese’s massive, overblown PBS series at times falls short: There’s nothing overstated (or re-created) about Furry Lewis’ letter to a friend. Instead, it provides a small window into explaining the powerful legacy of America’s most enduring and purest music form.

Furry Lewis is just one of a hundred blues legends that “Sweet Home Chicago” touches upon, though many popular music fans might recognize his name, if only through the 1976 Joni Mitchell song “Furry Sings the Blues.” His letter survived because he wrote it to Charlie Musselwhite, a young upstart harmonica player he had befriended, and Musselwhite saved it, along with many other pieces of memorabilia from the time. Musselwhite, like Lewis, was originally from Memphis, and “Sweet Home Chicago” is in truth more about the evolution of the blues, created in the cotton fields of the Delta, and eventually commercialized in northern clubs, than it is a celebration of Chicago alone. The exhibit’s great strength is how it illustratesthrough maps, audio clips, and photographshow blues mirrored the migration of African Americans traveling north to escape Jim Crow laws and plantation shackles. Muddy Waters left Stovall Plantation in 1943 when he complained that his pay (22 1/2 cents an hour) was substandard (whites doing similar work made 27 cents). Muddy asked for 25 cents and was fired, a small turn of history that helped launch the single most important blues artist.

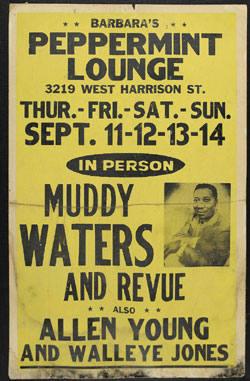

EMP’s exhibit displays two of Muddy’s guitars and several pieces of rare memorabilia. As Keb’ Mo’ says in one of the videos, “Muddy Waters is the connection between the Delta and Chicago,” and the exhibit uses his transition as a baseline. A 1964 clip from an American Folk and Blues Festival concert finds Muddy in top form, singing “Got My Mojo Workin'” with the kind of understated elegance that made him both the prettiest blues singer and the form’s truest ambassador. By contrast, several Howlin’ Wolf clips on display are so over the top that fans of punk will see elements of Nick Cave or Johnny Rotten in the way Wolf connects with a crowd through his massive eyes and his deep growl.

THIS IS THE biggest exhibit EMP has ever undertaken and it has to rank as the museum’s best effort to date. EMP Director Robert Santelli is a blues scholar himself and exhibit curator Jim Fricke scoured the globe for artifacts and memorabilia that hadn’t been seen before. “Charlie Musselwhite was one of the keys,” Fricke says. “I called him up and said, ‘Do you have this and this and this?’ and everything I asked him, he said he had. He had saved all this stuff and it was priceless.” Nothing could be more priceless than Musselwhite’s collection of “business cards” from the era: Most of the blues playerseven famous names like Jimmy Reed, Junior Wells, Elmore James, and Bo Diddleydidn’t have official cards, so they wrote their home addresses and numbers on paper or napkins instead. A second level of players used their day job cards: Jody Williams installed burglar alarms, while Johnny Shines was an “interior decorator” (house painter) when he wasn’t playing slide guitar or traveling with Robert Johnson.

THERE ARE A few miscues, perhaps a result of putting on a large exhibit in an era when EMP is cutting budgets and staff. In the past EMP acquired the bulk of its exhibit material, but “Sweet Home Chicago” relies heavily on loaned material, which leaves some holes in the breadth of the artists included. While the exhibit itself is well presented in the basement space south of Sky Church, simple signage would help patrons start in the Delta and follow the proper order of the display. If you enter the exhibit and turn right, you are suddenly looking at Eric Clapton’s shirt and wondering what that has to do with the blues.

Eric Clapton’s shirt? The only true blunder in “Sweet Home Chicago” is padding the exhibit with an attempt to connect blues legends with modern artists. If there is anyone alive who doesn’t know that Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Rolling Stones mined the blues, they certainly wouldn’t bother attending an EMP exhibit. Martin Scorsese fell into this same trap in his PBS serieshe, and several of the directors involved, made such concerted efforts to connect the blues to modern rock artists that the stories of the blues players themselves seemed like backdrop, rather than the focus.

The crass marketing of the Congress- declared “Year of the Blues” is bound to offend purists. Yet EMP’s exhibit, of all the many blues-related events this year, has the truest heart, if only because the simplicity of artifactslike a flour sack with B.B. King’s face on it. Like Furry Lewis’ letter to his friend, these priceless pieces of American cultural history tell a back story that can’t be glamorized, put on a T-shirt, or explained in a sound bite by Bonnie Raitt. The theft of his pants, shirts, and even groceries, wrote Lewis to Musselwhite, had “put me in bad.” His words may be the most eloquent and simple explanation of the blues yet written.

“Sweet Home Chicago: Big City Blues 1946-1966” shows at Experience Music Project through Sun., Jan. 4. Tickets: $19.95; $15.96 seniors, military and youths 13-17; $14.95 children 7-12; free for children 6 and under. The Blues radio series airs at 2 p.m. Saturdays on KUOW-FM (94.9) and at 11 a.m. Saturdays (noon on Oct. 11 and 18) on KPLU-FM (88.5).