One fateful afternoon when I was 10, I shuffled into the kitchen. Jodie Foster had just been on television, chatting up her new movie. I lamented to my mom, busy making dinner, how jealous I felt. Foster was only a few years my senior, yet she was a huge star; I’d barely made a dent in community theater. My thespian gifts were languishing in the suburbs of Northern Virginia.

My mother stopped stirring. “I don’t think you’ll ever be happy,” she sighed.

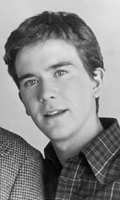

Mom’s prophecy seemed to come true in high school. Inspired by Sylvia Plath, I churned out angst-ridden poetry chock full of sunless skies and broken glass. While other boys emulated Don Johnson by nurturing their faint five o’clock shadow, my masculine ideal was Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People, and I haphazardly hacked away at my locks to recreate his suicidal opening-scene coif.

Music provided my only solace. Forlorn souls who’d already split this mortal coil—Nick Drake, Sandy Denny—held special sway over me. My favorite song was Richard Thompson’s lullaby “End of the Rainbow,” which lyrically confirmed the fate laid out for me: “There’s nothing at the end of the rainbow/ There’s nothing to grow up for anymore.”

By college, I’d evolved into the quintessential Sensitive Boy. Stale clove cigarette smoke permeated my secondhand cardigan sweaters. Cumbersome Clark Kent spectacles corrected eyesight weakened from hours spent poring over Baldwin and Bataille. The Smiths, Lloyd Cole, and the Wedding Present ruled my turntable. Although my boyfriend doted over my every whimper, I knew we were doomed, because loneliness and disappointment were all my idols’ songs foretold.

But Sensitive Boy quickly bit the dust when I moved to New York after graduation. One evening, shortly after my arrival, I brought home a guy I’d picked up at the corner bar. Next morning I offered to loan him a clean shirt—he’d spilled wine down the front of his—for the walk home. I dug out a sponge-painted one which read “The Boy With the Thorn in His Side,” and handed it over, with the understanding he’d return it on our second date.

It was months before I ran into this drunken rou頡gain. Not only had he forgotten about my homemade Smiths T-shirt (long since discarded in another East Village bedroom, no doubt), but my face drew a blank, too. After a few more similar incidents, loneliness and disappointment ceased to seem romantic. Goodbye Sensitive Boy; hello Mr. Bitterness. I scoffed at milquetoasts for praising Sebadoh, and decried Morrissey to anyone within earshot.

You’d have thought relocating to the Pacific Northwest, Sensitive Boy central, might have made a chink in my armor. But by the time I got here, I’d spent so long idolizing Henry Rollins—the anti-Morrissey—that my once-sloppy heart had shriveled into a raisin. I’d forged artistic success and a decent upper body via self-discipline and relentless negative reinforcement. If I so much as looked at some cute sad sack in a zippered sweatshirt and knit cap, an angry voice in my head taunted me till I turned away. I was more alone than ever, but because I’d deliberately chosen this path, and thus was master of my own destiny, I believed I’d transcended the loveless lot of Sensitive Boy.

Recent events have forced a reappraisal of my position. First, I came down with the flu. Through the feverish delirium, my inner Rollins berated me for lying in bed like a spineless weakling. But part of me was relieved to feel helpless. So I told that grumpy inner voice to shove a sock in it and enjoyed a long convalescence while listening to great, heretofore ignored Sensitive Boy CDs: No Memory by Portland’s No. 2, David Garza’s new Kingdom Come and Go, Blackbird by Joel R.L. Phelps and the Downer Trio.

Since my recovery, I’ve been getting back in touch with my neglected Sensitive Boy side. I took in a gig by Massachusetts singer-songwriter T.W. Walsh, whose melancholy How We Spend Our Days is the newest title from Made in Mexico—Sensitive Boy indie label par excellence (Pedro the Lion, Damien Jurado)—and felt right at home. A new friend gave me a mix tape featuring Jeff Buckley, Richard Buckner, and Mark Eitzel, and it’s rarely far from my stereo.

Yesterday at the gym I wound up working out next to a guy in a Rollins tour shirt. He was fit and focused, and looked utterly unlovable. Not loveless—unlovable. That was my final sign. I don’t know what I was thinking all those years I tried to cauterize my emotions, but (for once) I’m delighted to admit my mother was right. I still believe Smiths’ albums should be handled with the same care afforded loaded firearms, but I’m very glad to be unhappy once more.