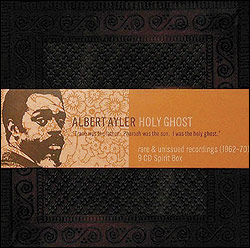

In 1983, Time magazine named the computer “Machine of the Year,” and everybody shuddered at once because it would be the machine of every year to come, too. Half of the material on Mark Stewart’s career retrospective, Kiss the Future (Soul Jazz), was released before that declaration, and half after. It’s the pivot around which the disc spins, with a pronounced wobble (four years surveyed before that date, 22 after)—the moment, maybe, when Stewart realized that the spiny beast with its tongue down his throat was his future, or our present.

Stewart had begun his career as the 17-year-old singer of a band sarcastically named the Pop Group, and the three earliest tracks in the scrambled chronology of Kiss the Future are Pop Group songs from 1979: “She Is Beyond Good and Evil,” “We Are All Prostitutes,” and “We Are Time,” exercises in steaming and leeching all the pop out of body music. The band had a steel-heavy post-disco groove, but everything else on their records was feedback, noise, and damage, and Stewart’s tuneless pronouncements were distorted until they oozed.

After the Pop Group broke up, Stewart hooked up with a group he called the Maffia—drummer Keith LeBlanc, bassist Doug Wimbish, and guitarist Skip McDonald (who’d previously been the house band at early rap powerhouse Sugarhill Records), along with producer-mixer Adrian Sherwood. And he figured out how to use computers to represent the world he saw coming: a foot pounding down over and over (a digital kick drum or a soldier’s jackboot) and endless, hollow declarations of freedom. “Control units are laid out geometrically,” he moaned in 1982, while reggae-ettes crooned, “Welcome to Liberty City.”

Especially on Kiss the Future‘s later recordings, LeBlanc’s drumming, and the computerized beat-grids that supplemented and eventually replaced it, become the bars of a cage with filth splattered against and between them. Stewart’s voice flies wildly around beats and notes, never in time, always sounding like a hot iron is hovering in front of his face. The Maffia worked with Stewart through the ’80s, and they’re also credited on the retrospective’s one brand-new track, “Radio Freedom,” which whacks and wobbles like their vintage material—Sherwood lards it with video-game noises and fragmentary info overload and cranks the beat until it warps. Stand in a crowded city’s densest commercial district in 2005, and what you’ll hear will be this, pretty much.

At the end of Kiss the Future, there’s a tiny nod to the pop moment that coincided with Stewart’s machine terror: A robotic voice from Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Welcome to the Pleasuredome” barks “welcome” every few seconds as Stewart screams, “The lunatics are taking over the asylum,” and then the whole thing fades into a brittle beat-box loop and a cluster of tape squiggles. It’s a curiously apt reference: Frankie’s mid-’80s label, Zang Tuum Tumb (co-founded by Paul Morley, about whom I wrote a few Smallmouths ago), was named after an Italian futurist slogan and originally intended as an outlet for experimental music.

That idea only really got as far as the records ZTT released by composer Andrew Poppy, which have just been reissued as the three-disc set Andrew Poppy on Zang Tuum Tumb (ZTT). His work (especially his first and best album, The Beating of Wings) was a sunnier kind of futurism: systems- and process-based compositional music, a clockwork mechanism with all the colors of a digital orchestra. But his records were marketed as pop (if a strange and elongated kind of pop), and the sounds of these pieces are the hyperreal sounds of hit records: samples, sequencers, booming drums, discrete rhythmic layers.

Poppy had briefly been a rock musician, although his main interest by the early ’80s was the repetition-heavy school of Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and especially Michael Nyman, whose music is often very clearly the inspiration for the pieces on AP on ZTT. (Nyman had dabbled in pop around 1980, too, in collaboration with the Flying Lizards’ David Cunningham; his “Mozart”/”Webern” single, in particular, has a familial likeness to Poppy’s “32 Frames for Orchestra.”) The Poppy works reproduced here are theory-driven creatures—the idea for a composition’s structure always precedes the composition itself, you can tell—but they’ve been made geometrically precise by the Machine of the Year and cast in the model of dance tracks. (The 12-inch remixes of “32 Frames” and “The Amusement” included here aren’t so far off from what, say, Cabaret Voltaire was doing in those days.)

Listen to any 20-second passage of Poppy’s work, and you’ll have an imperfect but reasonably reliable idea of what the next 20 seconds will be like. His future landscape is a sparkling city, laid out at right angles, kept in line by the same kind of omnipresent surveillance that Stewart rails against—”All’s well in the world of interception/They’re listening in,” a voice declares. And both of them were sort of right about the sound of the world to come. Down on the street, 2005 sounds like Stewart imagined; ride the elevator 10 smooth flights up to the office, and you’ll hear the rhythms Poppy knew the computer was bringing.