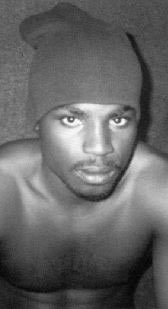

Anerae Brown is one of hip-hop’s least-known, most unlikely prolific MCs. Since 1992, Brown—whose nom de rap is X-Raided (or, at times, Nefarious)—has released no fewer than five solo albums on tiny Bay Area indie stalwart Black Market Records, including the recent Vengeance Is Mine. X-Raided is a clever MC, one who updates traditional gangster tales with a healthy dose of reflection. Over the years, his flow has evolved from gruff and bumpy to downright intricate and sometimes tongue-twisting. And his imagery, once trite and unexceptional, is now lucid and well drawn.

One catch: Brown is behind bars and has been since 1992, when he was jailed for participating in the murder of Patricia Harris, the mother of a rival gang member. At the time, the 17-year-old Brown was banging with the Garden Block Crips, and the murder was part of a home invasion gone wrong. In court, the alleged triggerman was acquitted, while Brown and two other accomplices were found guilty.

Part of the state’s case against Brown was his lyrics. Just prior to his arrest, Brown had released his first album as X-Raided, Psycho Active. Prosecutors found what they believed were lyrics referring to the alleged murder on the song “Still Shooting”: “I’m killing mamas, daddys, and nephews/I’m killing sons, daughters/And sparing you.” Interviewed at the time, Brown protested that the lyrics were taken out of context. Indeed, that section of the song refers to the aftermath of a domestic dispute, not a gang rivalry, but the prosecutor later told The Source that he introduced them to demonstrate “Mr. Brown’s possible association with gangs and the spirit of gang mentality.”

Violation of the First Amendment or not, the use of Brown’s lyrics helped to convict him in 1996, resulting in a 31-year sentence. Yet just before the conviction was handed down, out came another X-Raided album, Xorcist. While awaiting the result of his trial, Brown had been busily penning songs. Sensing, no doubt, that his freedom was about to be snatched away from him, he worked the prison’s pay phone system to his advantage, holding one phone playing the beat up to his ear and rapping into a second phone. The result is far from polished, but it was as true a document of life behind bars as any Lomax-documented prison toasting.

The X-Raided tale got only more bizarre last year, when his third album, The Unforgiven Vol. 1, was released. Not a fuzzy affair like its predecessor, this album featured stunningly clear vocals that baffled prison authorities, as did the declaration on the album’s back cover: “All of the recordings contained on this CD were made between 12.1.98 and 2.15.99,” dates Brown was clearly incarcerated. It was later discovered that a prison guard, Roy Castro, helped smuggle recording equipment to Brown, but that was only the beginning of the controversy. Soon after word of the album’s completion made it back to prison inmates, a gang war erupted. Brown was attacked and had to be placed in protective custody. Meanwhile, Brown, now a convicted felon, could be sued under California’s “Son of Sam” laws to prevent him from profiting from his notoriety. Nowhere on the album, however, nor on his subsequent ones, does Brown make any specific reference to the crime for which he is imprisoned. If anything, these latest records show a more reflective, more aware X-Raided. Granted, these albums aren’t documents of prison self-discovery like Eldridge Cleaver’s book Soul on Ice, but they’re legitimate artistic expressions. On “Write What I See,” from Brown’s latest album (also drawn from those illicit recording sessions), he practically trips over his own tongue trying to spill his vision, eventually asking in defeat, “What the hell am I supposed to write?/How can I compose nice/When I’m sitting in this cell?”

The next track, “Hold On (What a Thug to Do),” takes Brown on a psychological roller coaster from naive, hopeful youth—”Fuck Good Times, I want some of that Cosby shit/Four-bedroom home, white trim with green/I’d be a doctor, regular American dream”—to the fall from grace—”I thought it would be easy/I was mistaken. . . . I went to the pen instead of college”—to penitence—”I made my bed, but it’s too hard to be laying in it/Fighting the drama but for some reason I’m staying in it.” It’s all sealed on the haunting hook, in which Brown groans, Tupac-style, “On the inside I’ve been dead for years,” and at song’s end, where he pleads, “Mama, excuse my behavior, please/Feel like my soul’s gone/Pray for your only son/Need you to be strong.”

Certainly, not all of Vengeance Is Mine taps the pain well so profoundly, but give Brown credit for not sensationalizing his most unseemly predicament. Whether he’ll be allowed to profit from his recordings is now in the hands of the California courts, which are also considering the constitutionality of the “Son of Sam” law itself. In the meantime, Brown claims to have over 100 songs recorded, waiting for release.