Our transmission expired in Ashland, Oregon, on Feb. 13, 2007 while we were pulling out of a coffee-shop parking lot. There wasn’t a rentable vehicle large enough for us within 100 miles, and we found ourselves reluctantly leaving our van and trailer behind and piling into two midsize cars to take the six of us—and our dog, Ruby—to the next gig in Portland, while a kindhearted mechanic attempted to fix it—fast.

Meanwhile, I was dealing with a severe staph infection that landed me in the ER. The doctor advised me to cancel the next week of the tour, as he couldn’t be sure the antibiotic would work. Plus, he said, “It gets worse before it gets better.” Stubbornness and heavy painkillers kept me on course. While florists, with their monopoly on vans, geared up for the biggest delivery day of the year, we limped along on a U.S. tour that started in Texas and would not end before the loss of another transmission in North Carolina.

Though the journey was marred with vehicle breakdowns, emotional collapses, and severe illnesses, I have mostly positive associations with many of the memories, all these years later. What seems on paper like a dark time had a lot of magic. When you extract the momentary fuckery, the turmoil, the pain, you start to realize how much beauty there was inside the various realities that were being played out. Whether viewed from the distance of time or space, the gentle essence of everyone involved with that tour is what stays with me to this day.

My band, Jesse Sykes and The Sweet Hereafter, had just put out its third album on Barsuk Records, Like, Love, Lust, & the Open Halls of the Soul, and was invited to support Sparklehorse, touring behind their latest, Dreamt for Light Years in the Belly of a Mountain. It would be the band’s first tour in five years, and 10 years after Mark Linkous (aka Sparklehorse) almost died in a hotel room in Europe due to some complications with drugs, which for a time left him partially paralyzed. I had been aware of his mythology and the darkness that surrounded it, as well as his battles with depression. I was intrigued, and assumed he was going to be an intense and interesting person, which resonated well with me.

I’d been a fan of the band, and it was an honor to have passed muster and been chosen to share this journey. He and I had the same booking agent, and I asked the agent to find out if it would be all right to bring Ruby along. When I heard back that Linkous was fine with that, it spoke volumes to me about his character. I liked him right out of the gate.

In many ways, the tour was both the last gasp of an old-school music business and our brutal introduction to the new one. It wasn’t all bad. This was before ubiquitous GPS, gadgets, and smartphones, before bands and fans felt the need to be plugged into the constant digital drip. You could walk into a dressing room and people would be talking instead of Twittering away. It was before Facebook “likes,” before Spotify. Before there were a billion bands on Facebook, there were only millions on MySpace. It was also the tour year that we realized we were playing to bigger crowds than we had when we supported our previous album—2004’s Oh, My Girl—but selling fewer albums. It marked the grand entrance to where we now find ourselves perched, unable to visualize what the future will bring in terms of sustainability and stability in a business that has only ever been as reliable as your van’s transmission.

As much as our band was tested on the tour, with more than its fair share of internal and external friction, it was nothing compared to the bomb dropped on the Sparklehorse camp—most critically on Mark Linkous.

We were playing Los Angeles’ Fonda Theatre on the eighth day when Linkous got the news that Sparklehorse was being “let go” by their label. I’ve often wondered why it can’t wait till someone is in a safe place before unleashing this sort of news, especially on a person known to have a propensity for severe depression. But as with any business, record labels make choices based on projected sales, not what is best for the spirit and soul.

Linkous was already part of the cultural lexicon when he was dropped. He was able to fill concert halls coast to coast. He was an “artist’s artist”—respected by cutting-edge colleagues in film and music. He had worked with Danger Mouse, David Lynch, and Tom Waits, and had toured with Radiohead. He was still vital, still creating with some of the most coveted artists of our time. Yet his label apparently could not see a place for him in the new shifting paradigm of the music industry.

Mark was fragile when the tour began, but he was engaged—spending time with fans and signing CDs at the the merchandise table. After the news, he seemed broken, quickly disappearing, becoming reclusive—not leaving his bus until he had to get up to perform. For a few days it was critically bleak. The tour seemed doomed. He developed the flu as we headed east, and by Detroit he looked green. The tour was “maybe going to be cancelled,” we were told.

I remember thinking how awful it must have been to have to process the news in public. It may seem small in comparison to something catastrophic—like a death or an accident—but it’s hard to visualize yourself dismantled from the vehicle you’ve relied on to get you where you need to go. It’s hard to distinguish where you stop and the machinery begins, and it would be impossible not to associate losing “it” with your self-worth and be left reeling.

Even though it was Mark Linkous who was being dropped by his label, I felt that emptiness too, because it affected the morale of all involved; all of a sudden there was this feeling of abandonment, like we were on the Island of Misfit Toys, souls adrift. I tried to reflect on the good things that were happening. The audiences loved his music, and, for better or worse, whether or not the system behind it was intact was of no immediate consequence to them.

One of the most viral music conversations of the year was in regards to an antipiracy essay written by Cracker/Camper Van Beethoven frontman David Lowery. Its most contentious point was his implication that a contributing factor to the suicides of Linkous and Vic Chesnutt—both his “dear friends,” and two artists with a history of mental illness—was their careers caving and ensuing impoverishment due to declining record sales, thanks to illegal file-sharing. I am in no position to say why Mark Linkous took his own life in 2010, but having witnessed part of the narrative firsthand, I am certain that being dropped from his label was a major blow to his fragile state of being.

Anyone who’s suffered a severe and debilitating depression knows that everything is amplified, yet the world becomes smaller—much smaller. Your palette, once rich with sounds, color, light, and touch, becomes rigid and monochromatic. You become more aware of mundane noises such as pipes and settling walls, your breath, your bones. You become more aware of the unseen corners of existence, because you find yourself constantly staring at ceilings from the bed you lie awake in, or corners of floors which you view from the bed you’ve fallen from—but chose not to go back to. You see a new world in these forgotten spaces—in the cracks between existence. You stop eating, and welcome discomfort and cold, because comfort reminds you too much of the possibility you no longer feel you have.

You choose to be down on the same level as the dust bunnies beneath the furniture—square one, ground zero for the soul, where being at the same level as a wad of dust, a forgotten clump of particulate matter, can provide a helpful reminder of what the last vestiges of a breakdown in the physical world can look like—the very last barrier the naked eye can still manage to see. Witnessing this unseen world grants a new vantage point that you might be able to rise above. There is hope embedded inside these ephemeral non-objects collectively giving you something to work with: “Today I am one up from this clump of dust. I can do this. I can evolve beyond this dark cavity of nothingness.”

Sadness and depression are not the same. Sadness can be beautiful, and there is hope in sadness. But there is no beauty or hope in depression, because of its brutal capability of whisking you far beyond feeling anything except pain and anxiety—an X-ray of what once was. It is only after depression subsides that hints of beauty can be found. Small traces of that residual shrapnel, embedded, start to reveal themselves as lessons taking on the shape of growth.

Depression is a journey. You don’t just end up there. It is part of a vast spectrum, a wide array of the machinery of your soul and the chemicals of your brain. And each person’s machine is different. There is no blueprint or manual equipped to deal with their nuances. It’s hard to say where sadness ends and depression begins, but in those grey areas that hover on the edge of the spectrum, there is still plenty of sweet meat on the bone that is prime for picking, and deserving of much examination later on when it subsides. This is where sadness can be your friend. It is the barometer that lets you know, in its absence or its re-emergence, if you are too far gone or coming home.

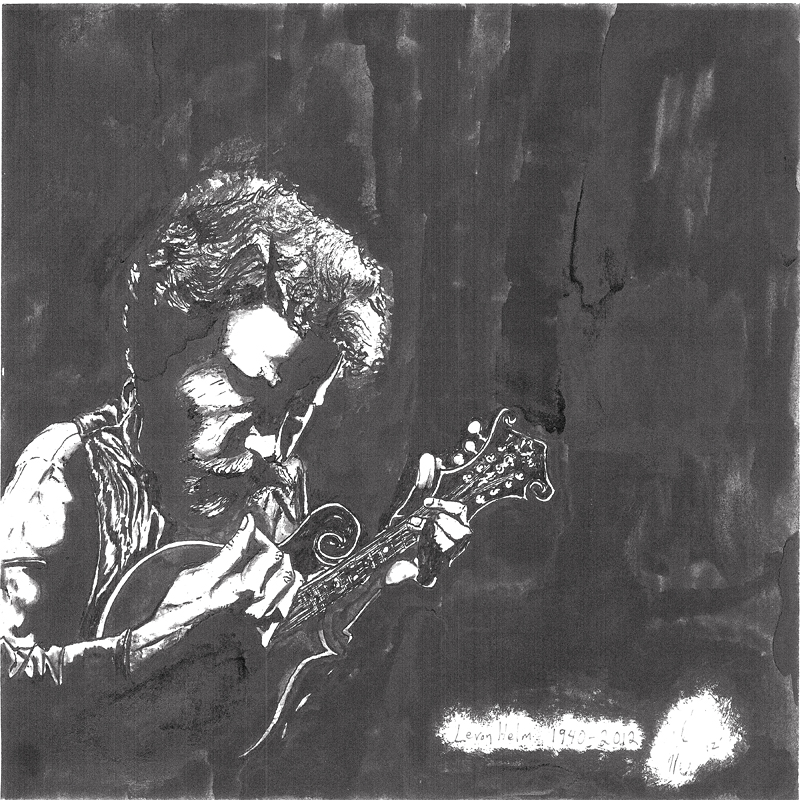

If you could hear sadness on a cellular level, this is the sound of Mark Linkous’ music: a voice that hovers so close to your ear—too close for some, familiar to many. Everything feels closer, hyper-realized, slow, and unapologetic. It is a beautiful place if you let it be. It is the space Mark Linkous occupied.

When our transmission died for the second time, we made it to an exit lane off the busy highway that luckily had a rest stop. Our van has a way of doing that—dying in a safe harbor. We were there for five hours before a flatbed came for us. Along the back roads of North Carolina somewhere outside Durham, we got lost. The mother of our guitarist, Phil, lived in the area and gave us directions via cell phone which we called out to the driver. Bill and Eric—our rhythm section—rode in the van on top of the flatbed, which was pulling the trailer as well. When we arrived at the venue, we were 10 minutes into our designated set, and the Sparklehorse folks all came rushing out, Mark included, and helped us load directly onto the stage.

In that brief moment I remember feeling embraced by them, feeling like we had bonded with them all, and I knew I was going to miss them when the tour ended a few days later. The show that night was raw and vivid, one of the best we’ve ever played.

What I loved about Sparklehorse as a collective was that their vibe onstage embodied a pure reverence for life and for music. They looked like characters out of a Tim Burton film, and Linkous was Edward Scissorhands—the perfect manifestation of two worlds colliding—a tender soul created from a machine’s soul, his creator dying before having completed his vision.

Mark would take his thick glasses off when he sang, and his eyes were always closed. All the band members possessed that stoic yet undeniable quality reminiscent of forgotten toys, injured souls wearing their dignified suits of armor cloaking their vulnerability. “Here come the pain birds,” he’d sing. Each night I’d watch them, listening rapt in the sorrowful beauty of the songs. “It’s OK to be sad,” I’d think to myself, “just don’t fall too far. When this is all over, you have to go home.” Home, where sadness ends and the darkness can overcome if you are not careful.

For much of the tour, Mark was too ill to hang out. But as he re-emerged, we were able to have an intimate moment that I’ll always remember. During our last conversation, he asked me about my band’s name. He was a big fan of the actress Sarah Polley, and wanted to know if we’d named the band after The Sweet Hereafter, a movie she had been in about loss, but also about transcendence and grace. Always a complex question, as there are a few answers intertwined, I told him what I tell most: It was first and foremost about a dream I’d had, a beautiful flying dream, with a narrator I never got to see but whom I could clearly hear behind my left shoulder. He took me over ancient cities, across oceans, and finally over a pine forest where a small cemetery rested. Under the brightest moonlight we hovered, and I could hear music that appeared to be coming up through the ground where the graves were nestled. He said to me, “Do you know what you are hearing?” and I asked “What?” He answered, “That’s the sound we make after we die. It’s what our souls sound like.” It was the gentlest music I’d ever heard, and the most beautiful, as it swirled up from, and beyond, the dirt.

We continued to fly past, and the music faded back into the ground and tucked itself away. When I woke up, I felt as if I’d been kissed by a divine spirit, a kiss with an essence that’s lasted for a decade. I told this to Mark, and I told him that the movie had been an inspiration, too. And then I told him, “But it also means death.” We both laughed: “Jesse Sykes and Death.”

We continued our journey without Sparklehorse, crossing Lake Pontchartrain, heading to South by Southwest. While we were having lunch in Baton Rouge, our trailer got rear-ended by a huge delivery truck, making it impossible to tow. During all our breakdowns, I’d been quite the trooper. Now I was tired. I curled up in the back of the van and just cried. I cried . . . and cried. Hours later we found a kindhearted fellow at an RV sales lot willing to weld on a new hitch for 25 bucks, and quickly.

Once again, we were allowed to stay on course.

We are the sum of many moving parts, a cosmic orchestra, but sometimes we stop hearing the music. Sometimes the smallest particles of the universe that make us who we are lose the ability to find the necessary balance and symmetry to sustain an elegant path, sending us into a state of panic where we no longer belong to the flow. This banishment is friction, a slow burn of opposition, which over time erodes, leaving us stripped to our core foundation, to where we no longer resemble the person we remember ourselves being.

People who’ve taken their destiny into their own hands clearly do not possess—if only for a brief moment—the mechanism that keeps us here, on track. All one can do is always listen for that music, but more important, believe in the possibility of always hearing the music—again and again.

Jesse Sykes is a singer and songwriter.