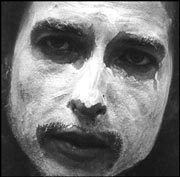

JOSEPH ARTHUR

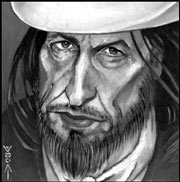

RUSTY WILLOUGHBY

EMP, JBL Theater, 206-770-2702, $15/$13 members

8 p.m. Sat., Oct. 12

“I’M CONSTANTLY WRITING. I write on the road—I record on the road, too—and when it comes time to put albums together, I really feel like any particular album, whenever it gets released, is like a snapshot of where I was at the time. Listening to Redemption’s Son now, I’m sure I had a plan—it sounds like I had a plan—but I honestly can’t remember what that plan was. I hope there’ll be a day when I can record an album and, four months later, still remember what it was I intended to do.”

Redemption’s Son, Joseph Arthur’s first full-length release since 2000’s highly- acclaimed Come to Where I’m From, is in actual fact something like the third or fourth album he’s assembled in two years. Maybe it’s even the fifth album—it’s hard to say. Arthur just kept giving the company record after record until they found one they could accept.

“I’d give them a bunch of songs, and they’d give them back to me and say, ‘Well, why don’t you change this or remix that, and we’ll take another listen.’ And at that point, I wasn’t really into remixing or changing anything. I was doing a solo tour, and Virgin Records [to which he was submitting the tapes] was going through a lot of difficulties, and each time I felt like that particular bunch of songs was done. So instead of remixing, I’d just give them a whole new collection of songs.”

If you’re not familiar with Joseph Arthur’s estimable body of work, the idea of assembling albums two a year until a company finds one it likes might sound suspect. Those who’ve heard Come to Where I’m From or 1996’s Big City Secrets, however, know that Arthur’s talents are neither commonplace nor pedestrian. The man is a viciously talented writer, in the tradition of Patti Smith—which is to say that if the words do just pour out of him, they’re generally the right ones.

Redemption’s Son furthers Arthur’s poetic vision by dressing his impressionistic lyrics (“Riding in my father’s car/Ashtray filled with his cigars . . . /Till he’s gone I won’t be free”) in weightier, more expansive instrumentation. Whereas Come to Where I’m From‘s arrangements were sparse, almost painfully intimate, the sound of Arthur’s new album is heavier and—though it’s an odd word, it absolutely applies—more theatrical.

“I think it is more theatrical,” Arthur agrees. “But I’ve always felt like writing music was ‘dramatic,’ in a way. People frequently tell me how personal my songs sound, but it’s just like a novelist—a person who writes a novel creates characters that aren’t one with the author. Songwriters should be allowed the same latitude. I write characters. I don’t see myself as being particularly brave, writing the things I write.”

Critics and fans do, however—it’s one of the recurrent themes in the commentary surrounding Arthur’s art. Similarly, it’s the reason Arthur’s lyrics resist excerpting; taken line by line, the songs on Redemption’s Son don’t go for the clever turn or the easy out. When he sings, “I’ve been so happy/being unhappy with you” (from “Favorite Girl”), the lyric is intended less as a stand-alone wisecrack than a clue to the narrator’s fucked-up state of mind—and it’s a state of mind that Arthur carefully, meticulously constructs throughout the entire song.

Similarly, Redemption’s Son is an album that rewards patient listening. At 75 minutes, it’s far and away Arthur’s longest statement, and one that moves deftly from bombastic noise to folk-rock acoustics throughout its length.

“I don’t think albums should, necessarily, be designed to be ingested at one pass,” he says. “I can certainly understand people’s complaints about an album’s length, or the multitude of directions on it; that’s the reason Electric Ladyland was my least favorite Hendrix record for years. But it’s taken me years to get my head around it, and now it’s one of my favorite albums, precisely because of all the things I disliked about it when I first heard it.

“When I put this one together, I knew I didn’t want to remake Come to Where I’m From,” Arthur says. “So I worked to make it bigger—the sound and the scope of it.”

He muses for a moment. Then: “Maybe that was the plan.”