GOURDS

Bumbershoot, Northwest Court Stage, $20

8:30 p.m. Mon., Sept. 2

On the subject of increased arts funding for America’s rural public schools, I am of two minds. On one hand, it might encourage young persons like the fellas who went on to found Austin, Texas’ Gourds. On the other, it might encourage raucous ne’er-do-wells whose idle hands long to make the devil’s music. Like . . . well, like Austin, Texas’ Gourds.

The Gourds are what the best American rock would sound like now if the British Invasion bands had all hailed from Harlan County, Ky.—a band whose lineal ties connect in equal measure with the Carter Family, Randy Newman, and Mississippi John Hurt. Part traveling absurdist medicine show, part sawdust-on-the-floor hootenanny, the Gourds are (you might have gathered) impossible to summarize. And how they do pick and grin, brethren and sistren.

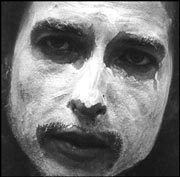

You might be knowin’ the Gourds—as frontman “Big Daddy” Kevin Russell would likely put it—from their mandolin-driven bluegrass cover of Snoop Dogg’s “Gin and Juice,” which enjoyed a staggering success via the Internet—and is often erroneously attributed to Phish—late last year. But if you’re unfamiliar with full-serving sizes like Gogitchershinebox (on which “Gin and Juice” first appeared), Dem’s Good Beeble, and the shaggy-dog opus Bolsa de Agua, now’s your chance to catch up; September will see the release of the Gourds’ sixth full-length album, the rollicking, ambitious Cow, Fish, Fowl, or Pig.

The best cow-related maybe-sorta concept album since Atom Heart Mother by Pink Floyd, Cow, Fish, Fowl, or Pig is also the funniest, with a delightful cast of characters (including Jorge the fruit vendor, the Short Guy from Chi-Town, and Sweet Nutty the CIA spook) and a bunch of food-related lyrics, to boot.

“Well . . . there’s really no unifying theme to it,” corrects Russell. “What happened was, we couldn’t get a sequencing we liked. So I ended up dividing the songs into two chunks and an ‘intermission,’ and I asked the guys and no one said it sounded stupid. So it’s more aesthetic than anything else. But then, most of what we do is unplanned and random.”

So scratch the “concept album” bit. But characters there are aplenty on this record—like the Short Guy from Chi-Town, a street vagrant who approached the band after an Arkansas gig and offered to give his “spiritual rap” in exchange for a small consideration. That solo lyrical performance, which serves as the album’s “intermission,” was captured on tape right then and there, in the venue parking lot. At the end of his rap, the Short Guy whoops in glee, as the Gourds, audibly impressed, cheer him and slap bills into his hand.

As in the most advanced hunter-gatherer cultures, nothing is wasted in the Gourds’ music. Take the mariachi horns on “Ham-Fisted Box of Gloves,” the N’awlins street-band vibe of “Ants on the Melon,” and the erratic rhythms of “Ceilin’s Leakin'”: A recent All Music Guide entry on the Gourds compared their dustbin-of-history compositional approach to The Band’s, and Cow, Fish certainly backs the point.

“Coming from Austin,” says Russell, “you’ve got all these different cultures that meet up in one place. And four separate ecosystems, too, which probably influences things in a weird subconscious hippie kind of way—anyway, people are very receptive to hearing a band try out different things. The straight country and southern rock bands are good, too,” he says amiably, “but after a while, it seems like people here encourage you to expand your style.”

Oddly, the Gourds “expand” their style on Cow, Fish by occasionally downplaying their giddy avant sensibilities—an influence of newest member Max Johnston, who takes a much more public writing role than on previous albums.

“Jimmy [Smith] and I have always done most of the writing for the band,” Russell offers, “and our writing is a little weird.” (From “Ants on the Melon”: “Wanna see you naked, baby/See your titties sittin’ up high/Mash taters and butter and all the other/We gonna do it up right.” Just so you know Russell wasn’t blowing smoke.)

“But Max’s writing is a lot more narrative. That song of his, ‘Blankets,’ that’s a beautiful, straightforward country song.”

And it is—a traditionalist heart-squeezer, as is the album’s closer, “Smoke Bend,” written and co-performed by Johnston’s father.

“Max was hot on having us do that song, and it’s a great one. But I said, hey, if you wanna give up one of your song slots, that’s fine. But I ain’t givin’ up one of mine.

“I mean, we wanted to encourage him, but hell,” Russell feigns indignation. “After all.”