Manhattan Island, late 2003, 4 a.m. Plantain Recording House stands dark, still, and silent. It’s rare; James Murphy and Tim Goldsworthy all but live in the West Village facility that’s served as the home of Death From Above, or DFA, the duo’s production alias, since 1999. But even the busiest superproducers need rest—unlike gear. Suddenly, the control room’s gloom dissolves as keyboards and black boxes flicker awake, displays ablaze with anticipation. “Stand by,” the studio computer barks through freshly fired-up speakers. “We only have a few hours. ‘Yeah (Pretentious Mix),’ take 15. Whatever you do, don’t crowd the timbales.”

At the very least, the (mostly) instrumental remix of LCD Soundsystem’s “Yeah” that ends the first of DFA Compilation #2‘s three discs begs for some kind of extrahuman attribution—the neodisco epic’s myriad machines sound like they’re having more fun than all of Babes in Toyland‘s characters combined. When the alpha clavinet and the reedy, brittle synth with which it’s destined to play toe tag fall into sync well before the 10-minutes-plus track’s halfway point, you can practically feel ecstatic grins break out across their keys. A flesh-and-blood percussionist plays fulcrum, illuminating the data orgy’s second climax with a flurry of hand-bloodying timbale blasts. Is he possessed, you wonder, or merely determined to hold his own in the melee around him? Or both?

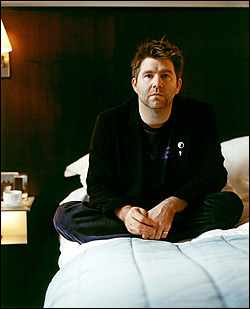

You could ask the same questions about the rest of Murphy’s life (he’s the bleeding meatware ringer), and the answer would be a definite yes. “For the sake of our mutual sanity, we’re not taking on any new projects this year,” he relates by phone from Plantain’s front office. The DFA co-founder and LCD Soundsystem auteur’s tone is warm; he speaks in proper paragraphs, like Hillary Rodham Clinton. Still, the stress in Murphy’s voice is both palpable and easily understood. He’s flying down the barrel of a schedule for which “brutal” seems but a pallid appellation, a flurry of touring (he takes care of all the five-piece live incarnation of LCD’s affairs), remixes, videos, and business-related matters. (DFA, an independent label since 2002, now has a distribution deal with EMI.) “As it is, I don’t see myself getting a break until September or October at the earliest.”

The worst part of Murphy’s current situation is that it renders songwriting all but impossible. “I write songs in my head,” he explains. “It’s a great merit filter; anything I don’t remember, I figure wasn’t worth keeping in the first place. But I have to build the entire song mentally before I record anything. If I lay one track down before the entire thing is completed, I lose the rest. This requires time—one thing I don’t have right now.”

Given the double-disc heft of LCD Soundsystem, released in February of this year, nobody should be pestering him for a little while. Sure, some of the singles (handily compiled on the second disc) go back a few years, but they’ve only gotten more nervous with age—much like the protagonist of 2002’s “Losing My Edge,” exhibit A of Murphy’s knack for writing lyrics that resonate like short fiction. Over a neutral electro backdrop, an aging hipster attempts to buttress his waning powers with a litany of accumulation that includes countless priceless pieces of prime record-geek bait, cutting the song’s pathos with a strong dose of humorous history.

If anything, “Daft Punk Is Playing at My House” is funnier. Simultaneously evoking the titular outfit and AC/DC circa “Dirty Deeds,” the frantic non-singles-disc opener chronicles the grand obsession of a kid who has saved for seven years to cover Daft Punk’s guarantee, booked the band, and made what he thinks are all the necessary preparations—including trundling a houseful of furniture into the garage. One of few songs on the disc with the absurdist immediacy of the singles (it’s since become one), “Daft Punk” seems more backward glance than manifesto. If any track points toward the immediate future, it’s disc one’s final track, “Great Release,” a surging confection that splits the difference between Brian Eno and Brian Wilson on a rolling bed of old-school minimalist hypnotics.

Like a good chunk of his newer material, “Great Release” dodges the dance-punk pigeonhole assiduously. “I like all kinds of music,” says Murphy. “The last thing I want is to be associated with one style of music or decade. Besides, there’s no quality control in people’s perception. To one person, [the] ’80s equals Cure; to another, Blow Monkeys. I’m not going out like that.”

He doesn’t really need to. DFA already have enough in the way of exemplary neo-post-disco diversity under their collective belt to earn a place alongside ’80s antecedents ZE. Plus, they’re generalists to the bone—and experimentalists every bit as much as Kanye West or Andrew Chalk. Manifest workaholic Goldsworthy spent the better part of the ’90s languishing in the notoriously indolent environs of Mo’ Wax and U.N.K.L.E. Given his love of house and techno and long-standing dismay at the lack of imagination therein, his solo debut—due later this year—might very well turn out to be a dose of undiluted futurism. And it might take Murphy a while to work the rock out of his system, which is fine. Meanwhile, the fact that he’s an admirer of Terry Riley with a genius for layering interlocking melodic figures, à la “Yeah,” looms. If ever he decides to bring that aspect of himself to the fore, John Adams had better watch his back.

LCD Soundsystem play the Showbox with M.I.A. and Diplo at 8 p.m. Wed., May 11. $18.50 adv.