Editor’s Note:

Seattle is experiencing a striking resurgence of interest in witchcraft and pagan/shamanic spirituality, especially within its arts communities. Tacoma’s influential proto-punk garage rock band, The Sonics, is performing this week in Seattle to celebrate the release of its new reunion LP, This Is the Sonics—the band’s first new material in 50 years. I thought it would be interesting to ask Meagan Angus, a learned witch active in Seattle’s art and music scene, to take a look back at the hit song that launched the Sonics’ career a half-century ago—1964’s “The Witch.” Angus penned the essay/poem/history lesson below.

Kelton Sears

, Music Editor

he archetype of the Witch is often maligned, and often misunderstood. She is by turns hunted, shunned, and lusted after. Alluring, repulsive, seductive, haunting, mesmerizing. You really have to get under someone’s skin to cause them to fling such a curse at you. How wicked is the woman to become a dark muse and inspire a song? How foolish the man to let such a harpy in?

“Say there’s a girl

Who’s new in town

Well, you better watch out now

Or she’ll put you down

’Cause she’s an evil chick

Say she’s the Witch.”

It’s November 1964. In another time she is a beat, a flapper, a suffragette, an Amazon, an Ethical Slut. She wears caftans, loads of silver rings, a thunderbird necklace made from abalone. She grows her own chamomile and pennyroyal; her house is filled with spider plants, aloe, shells, crystals, dried flowers, with an iron horseshoe over the front door and bay leaves on the windowsills. Piles of books by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Shirley Jackson, Brion Gysin, John Neihardt, Audre Lorde. It smells like cinnamon and musk. Her strange ink and watercolor art covers the walls. She’s from somewhere else. She smokes grass. She sits back in a wicker chair, sipping a steaming cup of tea, after flipping over the Link Wray album again. Her hair shields her face as she leans forward to roll another joint with long, spindly fingers, and casually tells you how she nearly killed her last boyfriend the first time he slapped her. Her mother stopped her and kicked her out of the house for “resisting the will of God.”

“My mother believes women were intended to serve men.” She looks you dead in the eye, passing you the smoldering joint, and asks your birthday. Your answer is a choking bark around the smoke.

“Pisces,” she sighs, “just like Jesus.”

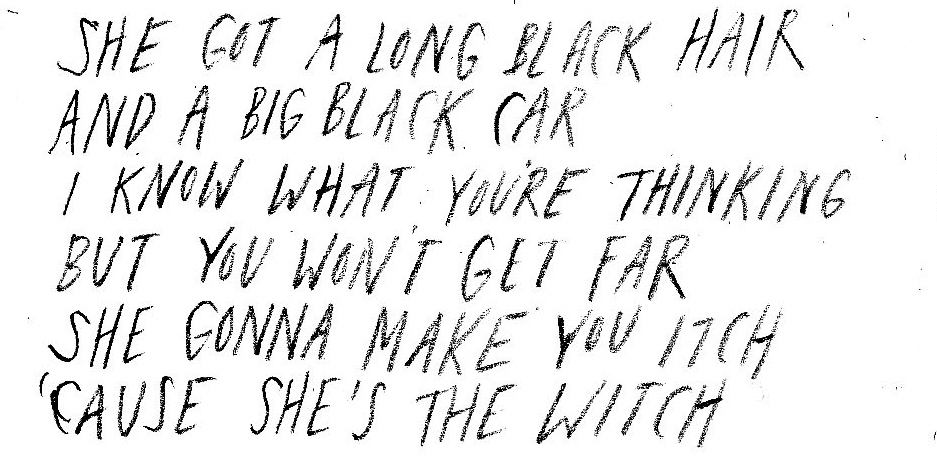

“She got a long black hair

And a big black car

I know what you’re thinking

But you won’t get far

She gonna make you itch

’Cause she’s the Witch.”

The Witch has always been a scapegoat for the festering guilt and shame in any community. She is seen as the foreign element, somehow disturbing the status quo with her very presence. Does that woman inspire lust in you? She must be a Witch. Did the widow with the nice parcel of land turn down your advances? Absolutely a Witch. Does she claim to heal, can she make a man fall in love, or tell your future?

Witch. Witch. Witch.

The wise woman, shaman, midwife has long been a source of scorn, ridicule, and suspicion for the patriarchy. We might even go back all the way to Lilith as our first example of a headstrong, cunning woman being made the root of ill. Depicted as having long black hair and wings, she is Adam’s first wife, before Eve, and considered herself his equal. Adam wasn’t very into that, and asked God to banish Lilith—give him a more docile wife. God did as he asked, and he got Eve. Lilith was cast out of Eden and became a demoness.

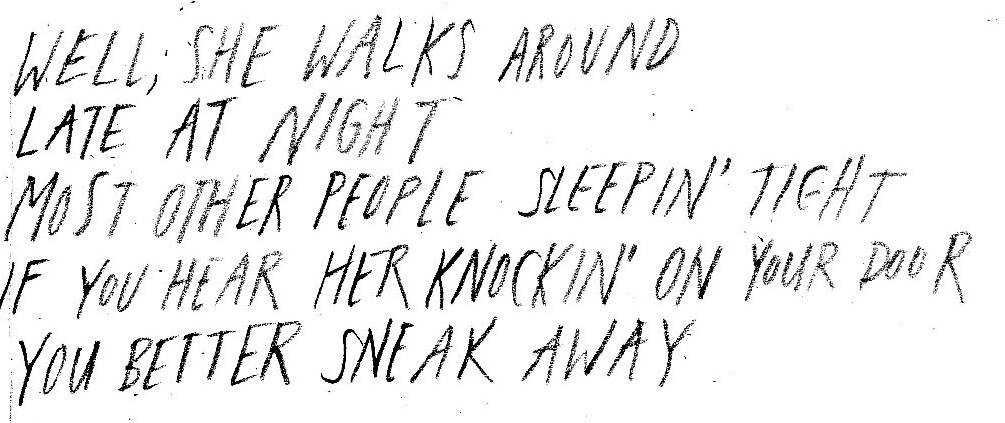

“Well, she walks around late at night

Most other people sleepin’ tight

If you hear her knockin’ on your door

You better sneak away”

In November 1964, the gender wars were raging and the second wave of feminism was in full swing. Simone de Beauvoir’s vanguard work The Second Sex was finally, but poorly, translated into English. It still managed to light an inspiring fire under the feet of a generation of American women, and continues to inspire women today. In 1963, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique came out, causing a ruckus in sleepy suburban households across the country. (Friedan helped found the National Organization for Women two years later.) The women’s-liberation movement was on the rise, marching arm in arm with the American Indian movement, the African-American civil rights movement, and the peace movement.

The general atmosphere from conservative America was waning amusement at these “uppity women,” largely considered a mischievous joke. Feminists became the scapegoat for everything from the rise of communism to the increase in UFO sightings. Above all, they were to be undermined as crazy, hysterical, delusional—and a clear threat to the stability of the ‘traditional’ family.

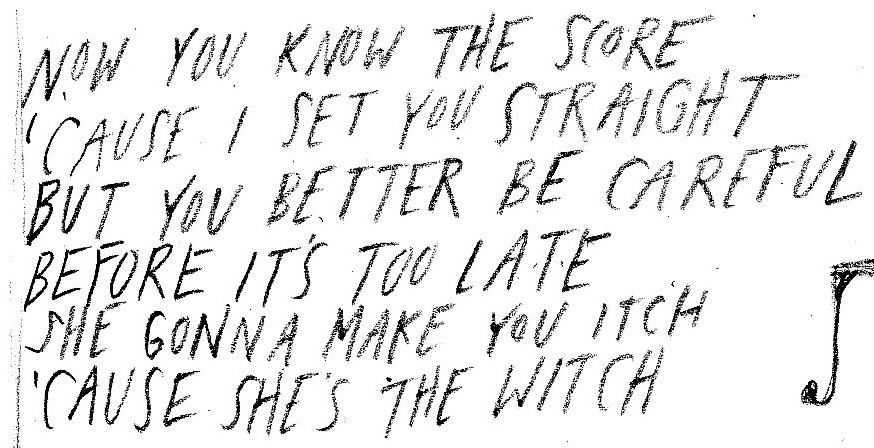

“Now you know the score

’Cause I set you straight

But you better be careful

Before it’s too late

She gonna make you itch

’Cause she’s the Witch”

In that crushing onslaught of men rewriting history, otherwise known as the Inquisition, the world almost lost a way of life. There has always been a Witch. A woman who lives at the edge of the village, who tends the h-edge of what is known and unknown. She knew the herbs to make you sleepy, or help your cramps, or get your cock hard. She could set a broken bone and ease the pain, or marry you under a full moon, wreathed in honeysuckle and woodrose, or make a tea of fly agaric and morning glory and send you out to meet the Gods and Goddesses at the blazing edge of the universe, and haul you back in again, helping you process all you had experienced. She was the arbiter of sex and death, the real Sex and Death, helping people be born, live, and die.

“Well you know you will

Say don’t you know

And do you remember

That I told you so

Gonna do you in

’Cause she’s the Witch”

Some Witches, like Jeanne d’Arc, went nova. As the Inquisition lasted well into the 19th century, most Witches went underground.

By the 1960s, many Witches were coming up for air. Alex Sanders, Janet and Stewart Farrar, Dion Fortune, Gerald Gardner, and Doreen Valiente were among a slew of authors who bubbled to the surface of the cauldron in the ’50s and ’60s, trumpeting a call to return to “the ways of the Goddess.”

Wicca, paganism, and other polytheistic traditions were fast becoming a spiritual trend with environmentalists, feminists, and revolutionaries for their emphasis on equality and deep reverence for the Great Mother, our beautiful planet Earth. Women across the world were once again taking up the threads of a power they had been stripped of 3,000 years before; and in this global discussion, in which women began to truly see themselves and each other as determiners of their own reality, women found this revolutionary view filtering into every level, from the sexual to the spiritual. A New Woman was being born out of the ashes of the old, and she was discovering, maybe for the first time, that she had no need to be burdened with the small worldview of a lanky guy in a leather jacket from Tacoma who was just trying to get laid. E

music@seattleweekly.com

Meagan Angus is an urban(e) witch, priestess, and notoriously uppity woman. She creates installation pieces for rituals, plays violin for the pagan–influenced chamber doom outfit Thunder:Grey:Pilgrim, and interprets tarot at The Vajra in Capitol Hill. She keeps her athame sharp, and believes The Way Out Is Through.

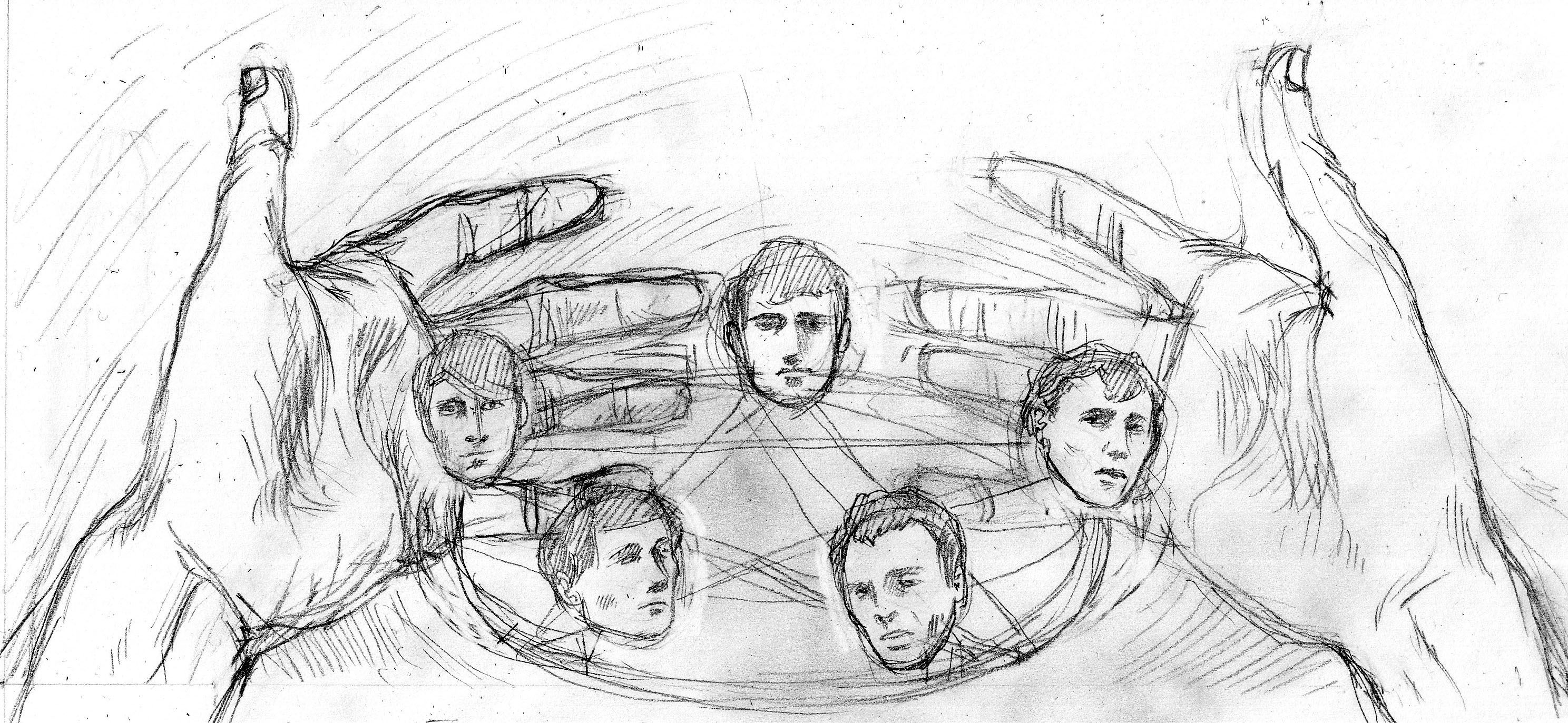

Julia Gfrorer was born in 1982 in Concord, New Hampshire. She graduated with a degree in painting and printmaking from Seattle’s Cornish College of the Arts. Her work has appeared in Thickness, Arthur Magazine, Study Group Magazine, Black Eye, and Best American Comics, and her graphic novel, Black Is the Color, is now available from Fantagraphics Books. Her last name rhymes with despair, and her heart is black as jet.

The Sonics With Mudhoney, The Intelligence. The Moore, 1932 Second Ave., 467-5510, stgpresents.org. $27–$47. All ages. 7:30 p.m. Thurs., April 2.