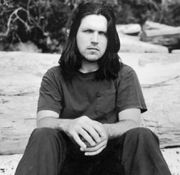

RICHARD BUCKNER IS a burly, California-bred, thirtysomething singer-songwriter with a knack for describing all the shades of every shadow on the dark side of the street. As a musical stylist, he is kin to such boundary-pushing folkies as Richard Thompson, Tim Buckley, Townes van Zandt, and Astral Weeks-era Van Morrison. Really. Everyone lumps him in with the alt-dot-country crowd, but he’s not such an easy collar. Buckner has collaborated with members of Tortoise and Gastr Del Sol, and the way he makes his husky voice do these weird, intricate, controlled loop-dee-loops is as much Jeff Mangum or whirling dervish dude as it is George Jones or Appalachian mountain folk.

Richard Buckner

Tractor Tavern, Tuesday, September 5

Mr. Buckner’s about-to-be-released fourth album, The Hill (October 5 on Chicago’s Overcoat Recordings), is his woolliest, gloomiest, and most gloriously fucked-up yet. It’s one track on your CD player, 18 musical sections composing one 34-minute whole. It begins with suspense-building organ runs punctuated by little feedback squalls that quickly morph into a huge, tuneful dirge—think Don Dixon producing a Hungarian funeral march with Peter Buck on guitar circa 1984. One section is sung in haunting a capella style, while most have full yet subtle accompaniment—cello, percussion, something that sounds like a zither. There are songs that rock and songs that don’t and gorgeous, short instrumentals interspersed throughout.

WHEN HE LAST played the Tractor, Buckner told of how much he liked Seattle (sure it’s cheap but I swear he was sincere) because after his prior show here he’d made enough money to go down to Tucson, Arizona, to record an album with old pals Joey Burns and John Convertino (of Calexico and Giant Sand semi-fame) and with stalwart producer J.D. Foster. This is that record. You’ll also remember, if you’ve seen him in the last few years, that he’s always worked in at least one curse word aimed at his record label, MCA. Well, now he has a new record label to be mad at, indie Overcoat (yet another cool label from Chicago, it’s home to Knife in the Water and Kingsbury Manx.)

The first words you hear on The Hill are “At first I suspected something,” an absolutely perfect beginning to a record. The words go on to describe a husband’s encounter with his wife’s jealous young lover. It is written in the language of American everyday speech, with just the right amount of detail to make the events seem absolutely real: “And I meant to kill him on sight/But that day, walking near Fourth Bridge/Without a stick or a stone at hand/All of a sudden I saw him standing/Scared to death, holding his rabbits/And all I could say was ‘Don’t, Don’t Don’t’/As he aimed and fired at my heart.” I don’t know if it’s the rabbits or what, but doesn’t that sound a lot like Denis Johnson?

That piece is called “Tom Merritt,” and it’s told from the point of view of a dead person—a trick Buckner has used before at least once. And it turns out the entire record is a series of tautly written, evocative epitaphs, all written in first-person from the point of view of various dead folks. A cemetery concept album!

AS CLOSE A FIT as the lyrics are to Buckner’s worldview, as finely set to the music as they are, none of the words were written by Buckner, but by a fellow named Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950). Buckner has a BA in English from Chico State and like most hipsters he’s worked in used bookstores before, which is where he found a copy of Masters’ Spoon River Anthology. The poems were originally published in serial form in 1914 and 1915 and soon thereafter collected. Spoon River was a popular tome in its day and has been compared to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Set in the fictional town of Spoon River, Illinois, the anthology’s poems were partially based on real people from Lewistown and Petersburg, Illinois, places near where Masters spent his youth. In a near-gothic yet modern manner, the book shows a harsher side of small-town life, something that had not been seen before. Voices from beyond the grave are rendered powerfully. Like old English folk ballads, it’s intense stuff: “Henry got me with child/Knowing that I could not bring forth life/Without losing my own/In my youth therefore I entered the portals of dust/Traveler, it is believed in the village where I lived/That Henry loved me with a husband’s love/But I proclaim from the dust/That he slew me to gratify his hatred.”

Buckner has said that he took the book home but did not read it until years later, when he slowly began to craft the poems into songs, some of which lack words but do refer to specific poems. The result is syncretic, absolute. The nearest corollary is visual artist Nancy Spero’s “Codex Artaud” series from the early ’70s, wherein the French poet Antonin Artaud’s legendary rage was transformed with splattery hieroglyphics as beautiful as they were violent.

On The Hill, Buckner’s nuanced delivery and the words’ simple, unrhymed style is weirdly contemporary. Listening to The Hill is like seeing one of Weegee’s stark crime scene photographs lovingly rendered by Saturday Evening Post painter Norman Rockwell. It’s resonantly American, yet it reminds us of where we are all headed, some of us in bad, bad ways. When you press play on The Hill, be sure to leave the light on.