CONSIDERING ELLIOTT Smith’s talent for layering each release with something new, Songs From a Basement on the Hill (Epitaph) feels like the natural progression of a gifted and obsessed musical mind with more and more resources at its disposal—and more and more time to fiddle with them, and more and more drugs to fuel the fiddling. Even given the jumbled, psychotic, fire-and-brimstone street speech tacked on to the end of “Coast to Coast” and the hyper–Sgt. Pepper vibe that casts an ambitious if happily disjointed yellow haze over the entire flow of the record, the most unnatural aspect of Basement isn’t found in any of the songs. What’s anomalous about the record is what we, as fans, now know.

Smith was guarded; you thought you knew him because his songs felt so personal, but he continually said they weren’t. Were it not for Da Capo Press’ Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing, by Benjamin Nugent, the deluge of Web-based murmurings after Smith’s suicide on Oct. 21, 2003, would still be enough to color the way we hear the record. Hell, anyone who had been to any of Smith’s last dozen or so shows probably knew he was using more and slipping. And reading Big Nothing in tandem with listening to Basement feels medicinal, but also incredibly invasive—not unlike the conflicted reactions to Journals, Kurt Cobain’s notebook ramblings compiled and released by Riverhead Books just a few weeks after Smith’s death. To steal a sentiment of Smith’s from XO, when people start talking—or even speculating—and the private becomes public, everybody cares, everybody understands.

Nugent, for his part, is quite confident in his grasp of Smith’s psyche. Although much of Big Nothing is essentially an oral history, Nugent, a former music and film reporter for Time magazine who shares many of Smith’s former ZIP codes, indulges in a lot of lyric interpretation. He reads the line “I’m floating in a black balloon,” from the Basement single “A Distorted Reality Is Now a Necessity to Be Free,” as “a picture of somebody in a state of unhappy isolation that has as its compensation a sense of freedom.” Fair enough, but any music’s sweetest, most sublime gift is that it is completely singular once inside the ear. What a song means to me has nothing to do with what it means to you. Sure, with a songwriter like Smith, whose giant talent—aside from his intricate, inventive guitar style—was pinpointing the most evasive, slippery truth in a roundabout yet succinct manner, chances are we’ll arrive at the same conclusions. And presumably, if you pick up Big Nothing, it’s because you’re hungry for whatever information you can get.

But what happens when artists die and others are left to disseminate their material is that editorializing can sometimes be mistaken for the truth. As Nugent reports, Smith told David McConnell, with whom he produced and recorded much of what wound up on Basement, “Whatever happens to me, don’t let anybody clean this up. Don’t let them put it through ProTools.” Clearly, this was someone thinking about leaving; any doubts about that evaporate in “King’s Crossing” when Smith sings, “I can’t prepare for death any more than I already have.” It’s also clearly someone who was concerned with what could happen to his work—his essence—once he was gone. You can’t accept that and have a completely clear mind as you continue to read, or even as you continue to listen.

Also uncomfortable are assertions like the one McConnell makes about Smith’s take on drugs and art: “That was a big thing for him, to take the artistic road instead of the high road or whatever. It’s definitely, ‘I’m going to do my record and I’m going to do as many drugs as I want, because art is not about being sober and it’s not about being some society figure, it’s about art.'”

If your lines or your syringes are in the next room waiting for you, you’ll find any reason to defend them. That’s AA 101. In the throes of junk, you come to believe that the junk makes you good. But if what Smith’s friends reported to Nugent is also true, if his earlier records were the products of a relatively clean guy who was just attracted to the paradoxically romantic culture of addiction, then he knew, somewhere inside himself, that his music was due to something far more significant than heroin or coke. To let an idea like McConnell’s stand for what Smith believed about his talent is damaging both to fans who might be struggling with their own use, and to Smith’s legacy as an artist.

E.V. Day, the N.Y.C. sculptor who was once Smith’s girlfriend, agrees. “I don’t think he needed [drugs] at all. I think he needed [them] to deal with the people and his conflicts with the relationships,” she told Nugent.

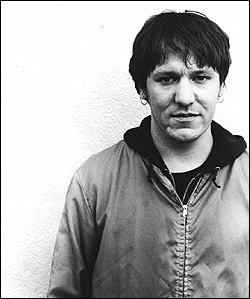

ELLIOTT SMITH wasn’t built with a strong outer shell. This much we always knew. Fragility and delicacy were, ironically enough, the backbones of every song he wrote—even when he moved into those Beatles-esque pop/rock tunes with bright tones. He was self- effacing and humble to a fault. And in the end, living a public life was simply too much for him. Too conflicting, too confusing, and too exhausting. Check this lyric, “I took my own insides out.”

Listening to From a Basement on the Hill, you expect the minor notes, the melancholy lyrics. What you don’t expect is the street scene that prefaces the song “King’s Crossing.” Before the keyboards come in, hard voices trade slang and the whirl of a white buzz comes off like ambient noise from Boyz N the Hood. The sadness in Elliott Smith is implicit; a soundscape like this one isn’t, even considering his habit of taking you down dark streets and into lonely bars, and his ever-increasing ease around fancy studio tricks. As you listen, the song becomes a sour reminder of how Smith’s fundamental style never changed, but the details often did—sour, because he won’t be around to surprise us anymore.