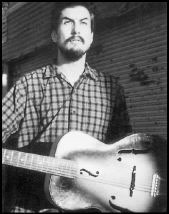

HOWE GELB

Crocodile, 441-5611, $12 9 p.m. Thurs., June 7

CALEXICO

Crocodile, 441-5611, $12 9 p.m. Fri., June 8

THIS WEEK, Howe Gelb and his Giant Sand bandmates, bassist Joey Burns and drummer John Convertino, are slated to appear on consecutive nights at the Crocodile. That they are not playing together as Giant Sand could be taken as a random coincidence or as a discouraging sign that this prolific unit is fraying.

From a border town in Mexico, where he’s searching for cover art for an upcoming Giant Sand record, Howe explains that since Giant Sand began to scatter a few years ago, these kinds of things happen to the three of them all the time. Take, for instance, a snafu in Austin that kept them apart during South by Southwest, a Paris airport crossover that was only discovered after the fact, and now this gig in Seattle.

“It’s an odd little twist,” is all Gelb is willing to say.

In a separate phone call from his Tucson home, Joey Burns nearly blames the booking agent and then says simply, “Howe wasn’t interested in doing a Giant Sand gig.”

Though the two men take different approaches to discussing their relationship and these strange near run-ins, both use the bittersweet Southwestern ambiance inherent in minor keys, sparse arrangements, and warm, present rhythms to inform their music. Gelb’s third solo offering, Confluence (Thrill Jockey), and Calexico’s new EP, Even My Sure Things Fall Through (Quarterstick), teem with timeless tales of lonesome roads and fables of disappointment. As lingering and lovely as Calexico’s often instrumental yarns are, Gelb’s deep, prodding vocals are twice as welcome to my story-starved ears.

Gelb, with his age and experience, understands all too well the personalities and distance. “I’ve got 10 years on Joe,” he says, “so I have a greater lack of ambition. And it’s never been that great to begin with. As far as [Giant Sand] becoming a form of pop music, it’s really difficult to imagine that happening. But with Joey, he’s at the age where he has the energy and the ambition. He’s developed this weird charm that he’s never had before. He’s almost like a politician.

“Joey was able to come in and size up Tucson and give the world Tucson’s music, even though he’s not from there,” continues Gelb; Convertino is from L.A. “The most interesting thing and the most addicting thing—of anyone’s music—is the mystery. It grabs you and haunts you and you can’t move away from it,” he says, adding with pride that it’s Calexico’s summation of the Southwest and their “delicious tones” that evoke that sense of mystery for him.

Burns interprets the shift in another way. “Howe’s always got five million things going on, so there’s no point trying to compete. And that’s why we love him. And also, that’s how John and I, over time, ended up doing some home recordings and stuff, ’cause we’re inspired.”

HAVING PRODUCED more than 20 releases in just over 15 years, the insanely prolific Giant Sand would seem to be a wellspring of inspiration. Burns and Convertino have had a truckload of success—apart from Calexico, they’ve served as rhythm section for Neko Case, Victoria Williams, Richard Buckner, and the electronic outfit Two Lone Swordsmen. Meanwhile, Gelb’s solo work keeps him contented and challenged, and he’s begun nurturing younger talent such as Portland singer/songwriter M. Ward and space rockers Grandaddy (whom he helped secure a deal with V2 Records).

Both Gelb and Convertino seem hesitant to say so, but Giant Sand has become less a band than a foundation. The record whose still-undecided cover art lured Gelb to Mexico will be a collection of covers, including Nick Cave’s “Red Right Hand” and the folk standard “A Poor Wayfaring Stranger” (featuring Neko Case and Kelly Hogan). Evidently, the three still make it into the same room at the same time when need be.

“I’m looking forward to just doing some Giant Sand touring,” says Burns. “It’s nice to have this variety of musical output and experience. It rarely gets overdone or dull and boring. Most of the time, 99.9 percent of the time, everything is really positive.”

“Life is a continuous poker game,” says Gelb philosophically. “You’ve got to fold ’em or bet the farm. It would have been cool if we could’ve continued the family business, but instead we have something different. . . . A franchise.”