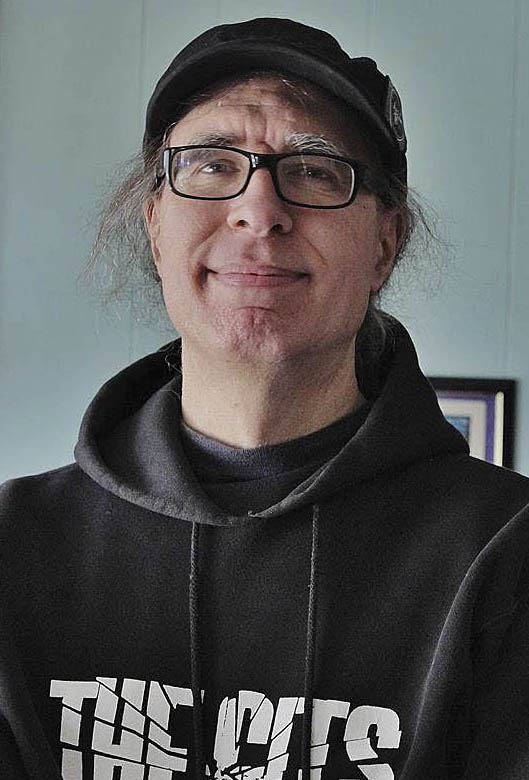

Despite having already recorded Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney, it wasn’t until Jack Endino wandered into a Hamburg bar to meet ’60s psychedelia purveyors Blue Cheer about doing a record for them that he realized grunge had reached its tipping point.

As he ordered a beer and sat down in a booth to wait for the band, a very familiar song blared from the jukebox, its chromatic punk riff immediately registering as “Two Way Street” by Blood Circus. The song had been recorded by Endino.

“Three-quarters of what was in this jukebox I had recorded,” he recalls now, perched behind the vintage Trident console at the Ballard studio he manages. “They had Swallow. They had the Tad 7-inch. They had Mudhoney. It was one of the most memorable things that ever happened to me, because it opened my eyes to the impact that we were having outside of Seattle.”

It was 1990, and though Endino’s career as a record producer had barely begun, he’d already made an indelible mark on music history.

You don’t have to write about the storied Seattle producer in the past tense, however. Endino is far from done. Recent projects have included recordings for Black Tusk and High on Fire, as well as the first new Sonics recordings in 40 years. Also, the demos Endino recorded for Nirvana’s In Utero will finally see the light of day with next week’s release of the album’s 20th-anniversary edition, a mammoth reissue that includes a remastered version of the record plus more than 40 unreleased demos, rehearsals, and a 1993 concert from Seattle’s Pier 48.

Endino knew early on that he was interested in music. At age 6, he began buying radios at local garage sales in his hometown of Southbury, Conn., and taking them apart. As an adolescent, he conducted similar analyses on the records he listened to, studying the different sounds you could get an electric guitar to make, the way reverb influenced the sound of a snare drum, the way harmonies were laid atop lead vocals.

Endino moved to the Pacific Northwest when he was 15. And while other high-school kids learned the names of band members, he paid keen attention to the producers listed on the back of his albums: Glyn Johns, Richard Podolor, Mutt Lange. “I had the geek gene from way back,” he confesses. “I knew that I liked the way some records sounded more than the way other records sounded. And the name of the producer that was on the back of the record seemed to have a lot to do with the sound of the record.”

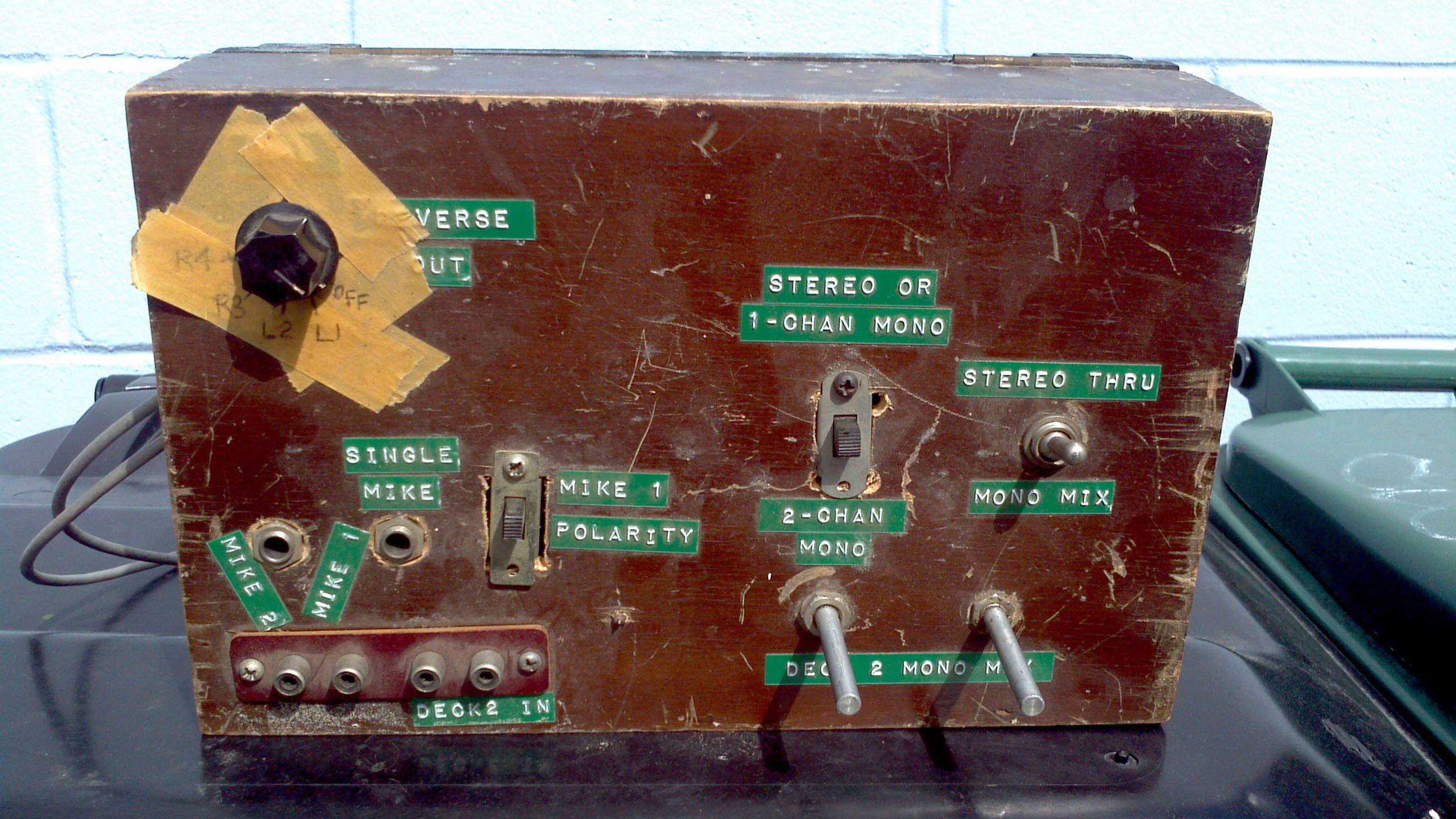

At the same time Endino was learning to play drums and guitar, he was experimenting with recording. He used two cassette players to bounce the signal of his guitar back and forth, a primitive version of overdubbing. When he got his first real recording gear a few years later—a Tascam reel-to-reel four-track and a six-channel mixing board that he bought from American Music—the budding engineer focused his attention on guitar pedals, layering them on instruments to see how they worked. “I would try and record like a studio using these guitar pedals,” he says. “The floodgates were open at that point.”

He honed his craft over the next few years, and in his 20s began to record bands—first his own, and soon thereafter Soundgarden, Green River, and Mudhoney, a holy trinity of soon-to-be grunge superstars. Through those early recordings, word of Endino’s recording prowess spread through Seattle. Once he finished with a band, they’d tell their friends about Endino’s high likability and low prices. Almost overnight, the young producer was very busy.

“A lot of these guys were really young at the time and didn’t have a lot of industry or studio experience,” says Jon Wiederhorn, co-author of the recent oral history of metal, Louder Than Hell. “They hook up with Jack, who’s a fellow musician, a guy they’ve hung out with and drank with, and at a time when there was a lot of slick commercial music going on in metal with Metallica and all the stuff coming off the Sunset Strip, he injected this raw energy. I think it was a camaraderie as much as it was a choice of having this expert technician.”

Endino’s recordings became synonymous with the sound of Seattle’s underground music scene: urgent, unpretentious, raging. The aural aesthetic he’d been developing all those years as a listener and then an engineer began to solidify. “Jack has an underground sensibility and a raw dynamic that fit well with these bands from the get-go,” Wiederhorn adds. “The garage-y punk roots of the Sonics have always been a part of the city’s music scene, and Jack was just great at capturing it.”

His approach was to try to record bands as they actually sounded in their rehearsal rooms and onstage. He made early recordings for just about every important Seattle band of the era, including Nirvana, recording the band’s debut Bleach in a handful of evenings in 1988 for a measly $600. Though these burgeoning Seattle bands each had their own sound, they shared a no-frills approach. The trick was to use technology carefully, making records that sounded big and modern without losing the emotion of what was happening. Endino wanted a listener to feel like you were right there in the room, bass rattling your chest, guitars assaulting your ears. “You take the music seriously, but you don’t take yourself too seriously,” Endino says. “That was the key to all the grunge bands.”

While Charles Peterson photographed the era’s bands and helped create Sub Pop’s early visuals, Endino was his audio counterpart, shaping the way the label sounded. “During that period, there was a sound that was Jack’s sound,” says John Goodmanson, a fellow Seattle producer whose credits include records by Bikini Kill, Nada Surf, and the Blood Brothers. “Where L.A. hardcore was super-dry and underprocessed, it was like Jack was trying to get [bands] to sound as good as Led Zeppelin or an AC/DC record.”

Before long Endino had a high profile. The bands he was recording were getting famous. They signed to big labels and had videos on MTV. Everybody, it seemed, wanted some of his mojo. Managers and major labels called, lawyers sent demos, but Endino was interested in almost none of it. “If I had moved to L.A. in 1992 when grunge exploded, I probably could have charged a lot more money and been established as one of those big shots, and I’d probably be making music that I hate. I don’t care about whatever the latest trend is in music. I want something that I record to still sound good 20 years from now.”

And they do. Bands are still calling—and not just because he produced Nirvana. “To call him a grunge producer is a misnomer,” Wiederhorn says. “He’s produced a great variety of bands. He just happened to be there with Nirvana and did a great job working with minimal resources.” Endino has made more than 400 records on four different continents, and even has a couple of gold records from Brazil (to go with the Nirvana plaques), courtesy of the band Titas.

And he’s playing music too, something he’s done all these years parallel to his recording career. He made six albums with Skin Yard and two with Kandi Coded, and will soon release his fourth solo album, Set Myself on Fire, for Ballard label Fin Records. Like that of the bands he loves to record, Endino’s music is loaded with hard-hitting riffs and big rock hooks, a potent combination of brains and brawn. He’s an underrated musician, overshadowed by his contributions as an engineer, but that’s partially because, like his production work, his songs are unassuming. They aren’t slick or overwrought, they’re efficient and economical—trimmed to perfection thanks to thousands of hours overseeing other bands’ songs.

Endino’s greatest legacy, however, may be his continued popularity, due in no small part to his unceasing work ethic and devotion to his craft, which have given him the luxury of working only with bands he wants to record. He is still reasonably priced, and makes just as many records for local bands as for big labels. He eventually came to realize that spending more time or money on a project didn’t make it more artistically viable. “I realized that the most important piece of equipment was me. All this technology, it’s just a tool. It’s your servant, but you can do it anywhere if your vision is clear and your skill is good.”

And that’s Jack Endino. If you need to find him, he’s probably at his Ballard studio, working on a record that will sound just as good in 2033 as it does today.

music@seattleweekly.com

Jack Catalog

The producer’s thoughts on his most notable releases.

Soundgarden, Screaming Life (1987) The first record that I recorded other than my own band. They were very meticulous in the studio, and they had very good ears.

Mudhoney, Superfuzz Bigmuff (1988) They came in and recorded virtually live. It captured a moment in time.

Nirvana, Bleach (1989) It took a series of evenings, I think five or six, three or four hours at a time.

Blue Cheer, Highlights and Lowlives (1990) The situation was extremely Spinal Tap in a lot of ways. The band was not the band I thought they would be, and the record was not the record I wanted to make.

Supersuckers, The Smoke of Hell (1992) Eddie [Spaghetti] wasn’t very confident about his singing, so he wouldn’t let me turn the vocals up very loud. If you notice, the vocals are kind of buried.

Titas, Titanomaquia (1993) I’ve made five albums for them, and they are one of the three or four biggest bands in Brazilian rock history. I became pretty famous there as a record producer because I made these really big records for this band.

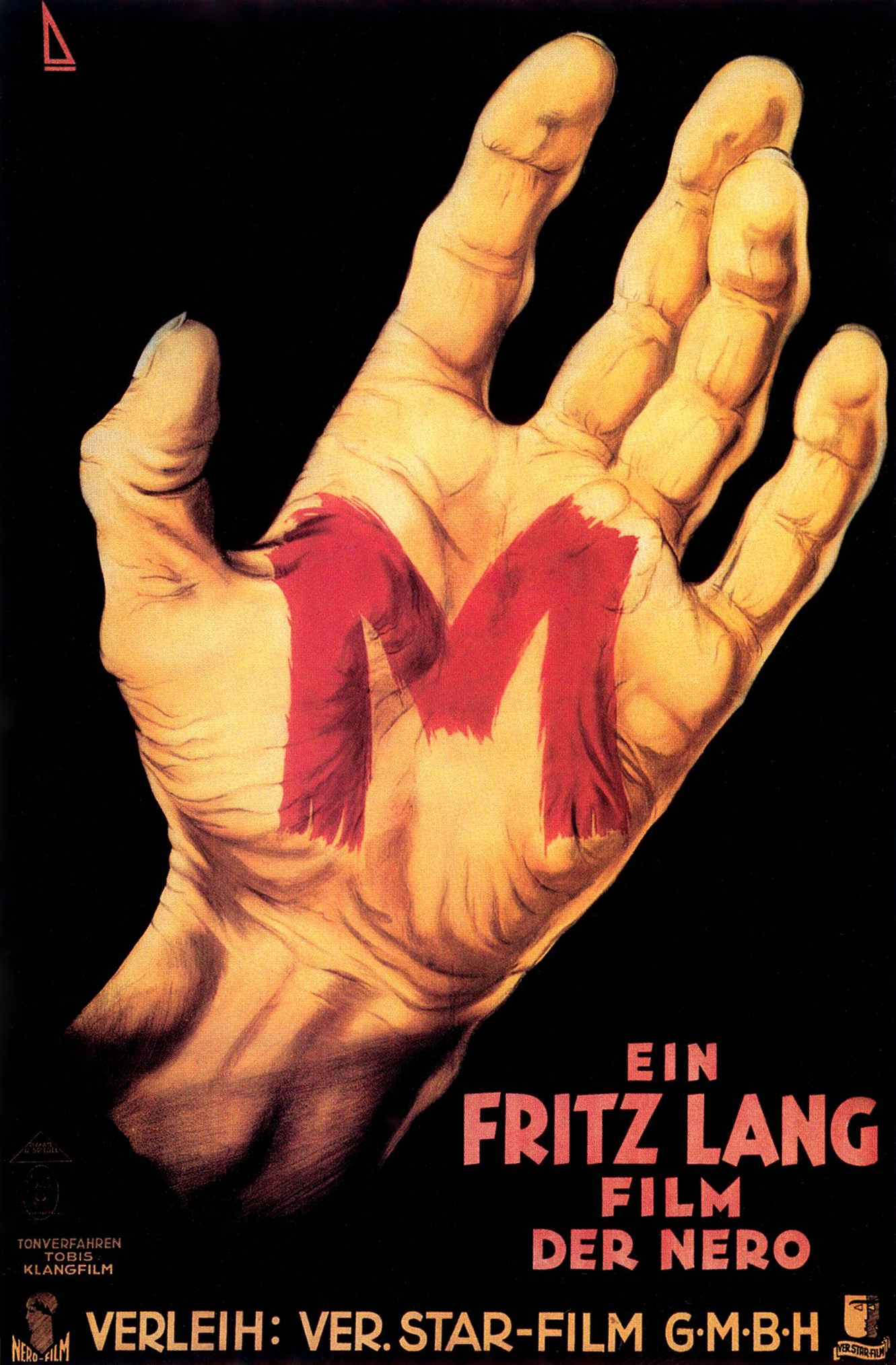

Seven Year Bitch, Viva Zapata (1994) There’s a song on it called “M.I.A,” about Mia Zapata’s murder; that is one of the most powerful songs that I’ve ever recorded for any band.

Bruce Dickinson, Skunkworks (1996) We hit it off on the phone. We’re the same age and we grew up listening to the same records. He was very humble and had a good sense of humor. He was a bit like a Monty Python character.

The Lonely Forest,

Regicide (2006) They won a battle of the bands at the EMP and one of the prizes was some free recording time. I tried to get Sub Pop interested in the band, but nothing happened.

High on Fire, Death Is This Communion (2007) I knew about High on Fire, and it was one of the few times that I specifically went out of my way to make it known that I wanted to record a band. Somehow we made it happen, and it turned out to be their biggest record up to that point.

The Sonics, 8 (2010) They had a big fight in the studio at one point, and I actually wondered if they were going to break up. And someone said, “No, no, they just do that sometimes.”