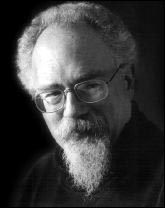

JOHN SINCLAIR

Barnes & Noble 1530 11th Ave. N.W., Issaquah, 425-557-8808

3 p.m. Sun., Feb. 9

Penny Caf鬠1707 N.W. Market St., 206-784-6426

7 p.m. Sun., Feb. 9

Ravenna Third Place Books, 6504 20th Ave. N.E., 206-525-2347

7 p.m. Mon., Feb. 10

“WE CAN’T REPLICATE that history,” John Sinclair says emphatically. “We couldn’t replicate it unless we were a bunch of poor, young, black men and women who’d grown up in the Mississippi Delta country in the 1920s and 1930s, carrying a box of food for the trip, riding, sitting up for a day and a half, on a train headed north.

“We’re not the people to replicate that,” he says again. “All we can do is, you know, emulate it.”

Hear the tone just right. Or, as John Sinclair might have put it himself 25 years ago, dig: Sinclair is no dilettante when it comes to the noisy, smoky, booze- and-wood-smoke-fragrant history of American musical history. Sinclair, a white man, a middle-class child of the 1960s and a veteran of the earliest maneuvers in our nation’s asinine “drug war,” is under no romantic illusions about the distance between himself and men like Robert Johnson, Charlie Patton, and Howlin’ Wolf.

But John Sinclair—writer, White Panther, historiographer, political theorist, former manager of the MC5, and onetime cause c鬨bre for no less than John Lennon, Bobby Seale, and Allen Ginsberg—knows whereof he speaks when he speaks of the blues. His recent book and CD release, Fattening Frogs for Snakes, is a project over 20 years in the works, a verse-and-music exploration of the history of the blues, from pre-Delta acoustic origins to Chicago electrification.

It’s an endeavor John Sinclair’s had in the works ever since he was a fixture of the Detroit-Ann Arbor music and politics scene, writing for underground papers like the Ann Arbor Sun and the 5th Estate and managing the MC5, the earsplitting musical-assault wing of the White Panther Party. As a white radical in the late 1960s/early 1970s, John Sinclair was a strong presence not only in the Michigan cultural scene but in the hearts and minds of his beloved Rainbow Nation—the young, long-haired “freeks” he loved and wrote for with such compassion and eloquence.

This is the part of the 1960s youth culture that latter-day revisionists such as P.J. O’Rourke have routinely attempted to dismiss as immature affectation, a calculated show of youthful revolutionary politics designed mainly to piss off one’s parents. But John Sinclair was sentenced to an absurd 10 years at Southern Michigan State Prison in July 1969 for possession of only two joints of marijuana (he was later transferred to the State House of Correction and Branch Prison in Marquette, Mich., 450 miles away from his family). When he arrived, he found himself welcomed by America’s first major crop of drug-law violators.

The history of John Sinclair’s release from prison after two and a half years is a remarkable story, and one only fully told (thus far) in Sinclair’s own collection of essays and prison letters from his rock revolution days, Guitar Army, now sadly out of print. One of the threads that runs through Guitar Army is Sinclair’s faith in music and poetry as transformative forces, as he states in an interview from prison: “I rebelled all through high school, but I went to college when they sent me there, and I tried hard to accept it. It was awful, but I got turned on to a lot of high-energy things when I was there—John Coltrane, Allen Ginsberg, you know? I could see there were other things you could do besides go along with the program.”

FATTENING FROGS for Snakes is John Sinclair’s epic poetic history of the blues, its migration from the rural South to the urban North (and the African-American movement that brought it there), and the men and women who made the music. The book is published by Surregional Press; the CD, expertly produced by Andre “Mr. Rhythm” Williams, is out on the Okra-Tone label. The project itself, described in cold type, sounds much larger than life, a fact its author readily admits: “I’ve been doing this kind of thing all my life,” he says, “but this is a huge project. Finally I just had to say, ‘It’s done.'”

The hour-plus CD, of roughly the first quarter of the book, presents Sinclair reading his text to the accompaniment of the Blues Scholars, an acoustic-electric outfit capable of switching settings—as the text dictates—from roadhouse bottleneck slide to amplified blues at a moment’s notice. Sounding half storefront preacher, half midnight DJ (a role he fills for New Orleans’ WWOZ radio when he’s at home), Sinclair growls, yelps, insinuates, and moans the history of the blues in a voice sounding decades younger than his 61 years.

It’s both a lesson—the scholarship behind Fattening Frogs for Snakes is beyond question, making it a valuable teaching tool as well as a damn fine listen—and a celebration of the music’s history. The text is fashioned from Sinclair’s own poetic retellings of the life stories of famed bluesmen (his riffs on Tommy and Robert Johnson are especially riveting) and first-person testimonials by those bluesmen, taken from primary writings and interviews.

“We live in a much different world today, musically speaking,” says Sinclair, “a much diminished world. There’s not a lot of historical awareness. Detroit-Ann Arbor used to have a very deep musical character. Now it’s all Kid Rock and Eminem, which, with all respect, doesn’t represent all the possibilities. The reason I moved to New Orleans after 50 years in Michigan was the musical crossroad here. The crossroad of America and Africa. New Orleans is alive, man. There’s a vibrant local scene, publishers and studios, all kinds of music. These days it’s as close to the Mississippi Delta as you’re going to get.”

The West Coast leg of John Sinclair’s current tour is a solo one—straight spoken word—but the rhythm of his delivery hasn’t slowed or gotten choppy over the past 20 years. The opening phrase of his monologue—”This is the Delta sooouuuuunnnd!”—rumbles like a steam train, kicking off the travelogue on a growly, gritty note. The rest is, literally, history. And it’s not over yet.

“I’ve been working on a jazz project, simultaneously with Fattening Frogs for Snakes, based around some pieces by Thelonius Monk. That’s harder in some ways. You can always find people in any town to play the blues. But if you run across someone who knows four or five cuts by Monk, in today’s world . . . ah, you’ve made a good find.”