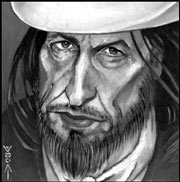

MISSION OF BURMA

SILKWORM

EMP Sky Church, 770-2702, $20

8 p.m. Wed., July 24

Clint Conley and I are developing a punkers’ Branson, a backwater sinkhole where yesterday’s Grand Old Buzz Cuts can go on pretending they’re famous. All we need are a location and start-up capital.

“It’d have to be an out-of-the-way city with cheap real estate,” Conley muses. And, we agree, it would have to be located where no one would care about the noise. Maybe now that Burroughs is dead and can’t stop us, Lawrence, Kan., is our best bet.

Given corporate America’s current woes, this doesn’t seem like a high-risk venture. Conley, at least, sounds optimistic. “Yeah . . . I think this might actually fly,” he says.

We’re only woolgathering this afternoon. But mere months ago, Conley was genuinely nerve-racked, wondering whether he and his old bandmates, Roger Miller and Peter Prescott, were simply fortysomething geezers playing dress up or whether there was some volume left in Mission of Burma after nearly 20 years.

“More precisely, I kept thinking, ‘What can we possibly do but disappoint everyone?’ I was terrified,” Conley admits.

It’s hard to know whether to take Conley’s modesty as false or real, since the reunion of Mission of Burma—how the fingers tremble typing those words—is precisely the sort of cosmic happening that makes us rock geeks wet our pants in nerdly rapture.

Cerebral, urbane, and brutally loud, MoB (as Bostonian aficionados once scrawled on the city’s alleyways and stop signs) damn near single-handedly created the template for ’80s college rock, indie rock, and egghead post-punk. Like the Velvet Underground, Mission of Burma parlayed a few recordings into a full-blown mythos. Their four-year life span left a sparse legacy, delivering only one full-length album, 1982’s Vs. However, had they released nothing more than the Signals, Calls, and Marches EP and the now-legendary “Academy Fight Song”/”Max Ernst” single, MoB’s place in rock’s noise-assault pantheon would have been assured.

At the time, of course, no one took much notice save for a small following in Boston and New York, where the band toured frequently. MoB were “closet progressives,” in Conley’s phrase—a group of unashamed pointy-headed intellectuals in the middle of a burgeoning punk scene. Mission of Burma incorporated psychedelia and free jazz into their melodic squall, sending all the needles into the red from the opening notes. As Jim Sullivan put it so accurately in a recent Boston Globe article, everybody in MoB played lead. It was, and remains, a unique and astonishing sound.

“The people who liked us liked us intensely,” says Conley now. “And the wayward track of history eventually meandered through areas that we’d explored—loud guitars and experimental rock. We were fortunate, in that time was kind to the memory.”

And what a lot of time it was. Guitarist Roger Miller’s worsening tinnitus prompted MoB’s breakup in 1983, after which invitations to re-form were routinely turned down. Miller and drummer Peter Prescott went on to make music in other venues, Conley got involved in television production, and Martin Swope (the unofficial “fourth Burma” who developed tape effects for the band’s live shows) moved to Hawaii. Time passed, as it will.

Then, in 2000, a slow accumulation of events drew Miller, Prescott, and Conley back into each other’s proximity. Conley began playing and writing music again; Prescott had recently disbanded his own group; and Miller, who’d always dismissed notions of a reunion, began to reconsider.

But the capper, perhaps, was the entire chapter devoted to Mission of Burma in Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes From the American Indie Underground 1981-1991. By considering Mission of Burma alongside such seminal acts as Black Flag, Sonic Youth, and Hsker D, Azerrad’s book at last placed the band where it belonged—in the company of fellow progressivists.

Miller, Conley, and Prescott agreed to a set of New York and Boston dates spread out over a couple of months to protect Miller’s ears. (He’s wearing firing-range ear protection muffs on stage—which, to a longtime Burma fan, is so undeniably right.)

“I had panic attacks before the Boston shows,” says Conley. “But afterwards, everyone said such nice things, and nobody made fun of us. We worked really hard not to embarrass ourselves. And I think we met the challenge.”

Two cities eventually became five, with a series of West Coast shows filling out the minitour. There are no plans to extend the reunion (quips Conley, “since people would probably get sick of us just as quickly”).

“People say ‘ahead of their time,'” Conley says carefully. “I’m not sure about that. I don’t think we’d be any more successful if we were starting out today. But we did manage to create a world that looked strange but had its own logic and sustaining energy. And when we started rehearsing for the new shows, it felt electrifying. I’ve never experienced an exciting rehearsal in my life, but the music still felt vital.”

Mostly, he suspects, that’s a result of its complexity.

“The music was rarely boring. We do have a few reductive punk songs: ‘Peking Spring’ was the first song I ever wrote. If they all sounded like that, I would feel like a bunch of oldies revivalists. Today that song sounds like warmed-over Clash.

“But you know, sonic assault cures a lot of ills,” Conley says quietly. “I just scream the lyrics really hard, they way I did 20 years ago. They were just as stupid then.”

info@seattleweekly.com