We’re never too far from our own existential yawps. At least we have the advantage of getting right in art what we can’t in life, whether we’re managing our mind(s) or paying someone by the hour to do it for us. That said, encountering 2004’s Puking and Crying, the second S release from Carissa’s Wierd’s Jenn Ghetto, is like stumbling across a crumpled missive on the street (or in the pages of Found magazine). From its visceral title to Ghetto’s scribbled message to her bandmates, “Thank you for always being there even when I lost my mind,” in the liner notes and, finally, to the musicPuking and Crying is every inch catharsis.

Opener “5 Dollars” is an ode to a small-towner slouching toward morbidity, and then cuts into “Falling,” slightly sweetened by electronic clips, cushioning the blow. “All I can do is hurt you,” she surmises—”you,” and much of herself. “I’m Fine . . . Bye Bye” feels for the ethereal, thanks to multitracking and psychedelic electro washes, but with nods to bruises and waking up lonely, never reaches beyond her arm span. Ghetto’s emotion on record and reserve in person seem to say one thing: Leave the singer to the song.

“I really didn’t want to be in a band,” Ghetto explains of the period spent recording Puking and Crying. She’d recently left Carissa’s Wierd, the mope-rock sextet incurring cultlike status in and out of town, and she’d spent several months writing and four-tracking. “I wanted to just make it and put it out, didn’t want to do anything with it or play shows; but logistically, being on a label, you end up doing that kind of stuff—and sometimes I just have a hard time saying no.”

Ghetto left Seattle for California and her hometown of Tucson in June 2005, citing “emotional problems,” the specificity of which she doesn’t disclose. Having returned early this year, she’s currently finishing demos for a third S record with collaborator Josh Wackerly (also of Panda and Angel), to be released by Suicide Squeeze in early 2007. The new record is, she offers quietly, “a lot about dealing with change, leaving friends, trying to get them back.” She calls it upbeat, but clarifies that it ain’t power-pop. “It’s not a happy record. Puking and Crying was really despairing, and [the new record] doesn’t go that far.”

Still, the new material is a joyful octave above Carissa’s slowcore slow dance, and is a sign that she’s in brighter spirits—perhaps owing to being back in Seattle, something she describes as “[initially] kind of a shock.” Maybe it was magical.

“We were just having a hard time, and I was having some problems,” she says, looking back on her days with Carissa’s. “I think the members of the band understood. It worked out really well for Ben . . . ,” she adds, understatement implied, of Ben Bridwell’s Band of Horses. “They seem to be kind of successful.”

Of the new material, Wackerly, who produced the record and supplies bass, organ, and electronics, adds via e-mail: “I think Jenn’s writing now is a lot more focused and complete. The songs are upbeat in tempo, but still the usual as far as subject matter and lyrics [are concerned].”

Wackerly met Ghetto after Bridwell gave him Carissa’s Wierd CDs. “The first thing I noticed was her voice,” he says. There is something to her voice that sounds very honest.”

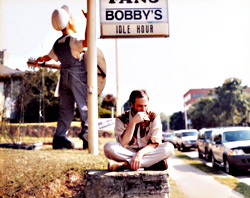

And that voice is not always easy to hear. Ghetto’s self-diagnosed “Extreme Stage-Fright” hits orange level as she faces her first live performance in more than a year. While excited at the prospect, she’d hoped to just “sneak onto a bill.” It was Wackerly who convinced her to do it. “Jenn is so much more focused and I think really wants to make S work this time. It used to be almost impossible to get her to play live. Now she’s more willing.”

It may be difficult for diehards to get over her former band. And Ghetto has remained an enigma in a way that illuminates her cult status.

“She’s a cult figure because her songs are so personal,” Wackerly says. “She writes exactly what is going on with her, and I think people can hear that.”

In other words, her words are right where they belong.