Despite his indie-approved credibility, David Berman has always been more poet than performer. His 1999 book, Actual Air, is filled with lucid, lyrical drifts that would be spoiled by guitar scales, even if they’re artfully damaged by erstwhile bandmate Stephen Malkmus. While the Yiddish word “mazik,” describes a mischievous, clever, or ingenious child (on which Malkmus has built a career), a “Silver Jew” is slang for the somewhat uncommon blonde Jew; or as a figure of speech, a mazik-come-lately—which is how David Berman chose to interpret it in the early nineties, just coming into his own as poet and trying to come up with a name for his band. Five LPs, a poetry book, and trip to hell and back later, Silver Jews have embarked on their first real tour. Clearly Berman has dug his way out of his psychological funk, but don’t go thanking the lord for it. Despite secular implications, Berman isn’t coming from a place of religion, but rather a longstanding literary tradition. Woody Allen called it the “Realists’ Trifecta”: pessimism, cynicism, and misanthropy; the richest source of humor. He’s built a career treating his own psyche by tormenting his characters. As a former art museum guard and attendant at the University of Virginia hospital morgue who sang “Sometimes I feel like I’m watching the world, and the world isn’t watching me back,” Berman seems dressed the part, much like Bellow’s Eugene Henderson finding inner peace among a foreign tribe; Kafka’s cockroach; an old Groucho Marx joke.

Though he’s lumped in with indie rock’s finest, it’s obvious Berman hasn’t cancelled his Paris Review subscription. Poems in Actual Air allude to both novelist James Michener and Mrs. Isaac Asimov, with a letter written by her husband on his deathbed. The reflective “Self Portrait at 28” predicts “We will travel to Mars / even as folks on Earth / are still ripping open potato chip / bags with their teeth.” “Classic Water” recalls “Those summer evenings by the government lake / talking about the paradox of multiple Santas / or how it felt to have your heart broken”; and in “From His Bed in the Capitol City,” “The Highway Commissioner dreams of us / We are driving by Christmas tree farms / wearing wedding rings with on/off switches / composing essays on leg room in our heads.” “The New Idea” plots our everyday dramedies in a way that’s plainspoken but poetic, citing “poorly conceived smiles” in office elevators, and the feeling that “no one asked me to design my life / to fit the dimensions of this situation.”

As in old country songs, Berman’s characters are trying to find love or redemption, whether in truck stops or the animal-like shape of a cloud. On the Silver Jews’ latest album, Tanglewood Numbers, ponies get depressed, chirping birds aren’t always happy, and the lovelorn live it out in bars and drug binges. But there are a multitude of happy endings heard in the duets between Berman and wife Cassie Marrett, who plays guitar in the band. “I was not born to be the center of attention in a crowded room,” Berman told Pitchfork, when asked why he separates poetry and music, adding: “I have always had my heart set on a certain kind of body of work I would like to leave behind. I believe that intermittent live performance has cut short the writing lives of touring musicians.”

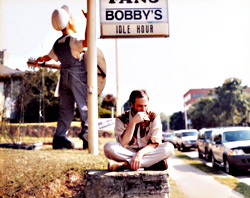

So what happens when the outsider plays to an audience, as Berman has been for the last few months? Not a whole lot, really. Videos posted on the Web of a Dallas gig provide visuals as nondescript as those lyrical “dimensions.” With the stage as his cubicle, Berman stands behind sheet music like it’s a literary reading, and his band is firmly in place. Why is what we’ve never seen before like everything we’ve seen before? Just as Mrs. Asimov, in Berman’s poem, writes, “as a Jew I asked myself what good are hidden things, as a Jew I admonished myself for asking,” we have a knack for reflexive questioning.

When Berman sings of “a place past the blues I never want to see again,” concluding Tanglewood Numbers, it’s all we need to know about his substance abuse and a suicide attempt (he’s since been through rehab). While working on Tanglewood Numbers, a nervous Berman swapped analyst for rabbi, seeking consultation about the inevitable press inquiries. In the end, his writing and recovery is a lesson for those who are struggling. There’s a Yiddish word for that too: mitzvah.