Sean Kinney sits in a booth in Belltown’s Via Tribunali, enthusing about his latest business venture as co-owner of the adjoining club, the Crocodile. After the legendary Seattle venue closed in 2007, Kinney became involved in its relaunch, despite the caution of his longtime friend Susan Silver. “I said, ‘Here’s my advice. We know nothing about the club business. Let’s not,'” Silver recalls. But both wound up investing, and the Croc reopened last year. “And it’s kick-ass!” says Kinney. “I know how to lose money,” he jokes after a pause.

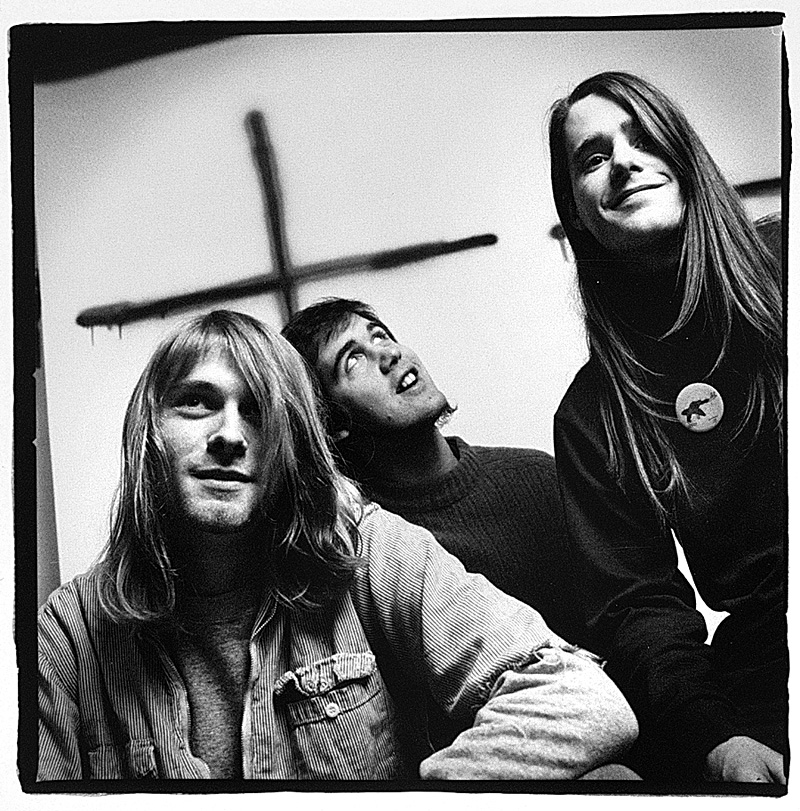

Kinney’s better known for his other venture, drummer for Alice in Chains (managed by Silver), which makes the club setting for this interview all the more appropriate. For the Croc’s rebirth mirrors what’s happened with the band that was once one of the Seattle scene’s “Big Four” of the early ’90s (with Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden), but which slid into relative obscurity due to lead singer Layne Staley’s well-documented substance-abuse problems. The band released their last, self-titled studio album in 1995; the following year, they played their final show. And in April 2002, Staley was found dead in his condo from a drug overdose.

Despite the turmoil that constantly plagued the band, Kinney had thought Staley would eventually turn his life around. “We never lost hope until the day we knew Layne passed away,” he says. “That was when I really thought, ‘Well, this is never going to happen.'”

But oddly enough, after what they assumed was a one-off benefit show in 2005, Alice in Chains is back, in a big way. Original members Kinney, guitarist Jerry Cantrell, and bassist Mike Inez (who joined in 1993) joined forces with lead singer William DuVall, and last September released Black Gives Way to Blue, which hit #5 on the Billboard Album charts, and whose first single, “Check My Brain,” snagged a Grammy nomination for Best Hard Rock Performance (alongside the likes of Metallica and AC/DC). A one-night stand at the Paramount this week extended to two shows because of public demand. “Nobody’s more shocked than I am,” Kinney admits. “I’m still shocked, like, ‘Is this really happening?'”

It’s a comeback any band would envy. Yet for all their past—and present—success, some insecurity remains. Alice in Chains has always felt like outsiders in the rock arena; Kinney even refers to the band as “the redheaded stepchildren” of the Seattle scene. “We’ve always been that,” he says, shrugging. “I don’t know why, but we are. And we’re cool with it, we don’t really care.”

In a sense, Alice in Chains were outsiders from the beginning. “Part of that was not being on Sub Pop,” says Silver. Nor did they rise from Seattle’s punk underground. As producer Jack Endino explained to journalist Everett True in Nirvana: The Biography, more bands came to him wanting to sound like Alice than Nirvana: “That was the easiest blueprint for the suburban metalheads to follow because Alice in Chains made the transition from metal into grunge, whereas the other bands had come from punk rock.”

Despite hits like “Heaven Beside You” and “Rooster,” and multiplatinum sales with albums like Dirt—something today’s beloved local bands like Death Cab for Cutie or Fleet Foxes can’t touch—a sense of feeling overlooked still lingers, and grates. Kinney recalls picking up an issue of Seattle Metropolitan for its cover story, “100 Years of Seattle Music,” which mentioned Alice only in Soundgarden’s entry: “Sure, Cornell was married to Susan Silver, who also managed Screaming Trees and Alice in Chains.” They’ve had seven Grammy nominations but have never won. “We made buttons for the last Grammy we went to that said ‘The Susan Lucci Award,'” Kinney jokes. “Ah, we’ll lose to Metallica again [this year]. They’re friends. They need another paperweight. I’m just glad that the Grammys even noticed what we’re doing.”

“You’ll be happy to know Kim [Thayil, of Soundgarden] voted for you this year,” says Silver.

“Good!” says Kinney. “Sweet. I mean, it’d be nice to win and it’s fine to lose.”

The resurrection of Alice in Chains came in the wake of a disaster—a natural disaster, the Indonesian tsunami in December 2004. While having a drink at the Premier club (now the Showbox SoDo) one evening, Kinney got the idea to put on a benefit show. “It sounds like a good idea, right?” he says. “I’m thinking it’s easier than it is. ‘I know some people!’ And the first guys I called were Jerry and Mike to see if they’d play.”

The benefit, held in February 2005 at Premier, featured other local acts (including Sir Mix-A-Lot and the Supersuckers); Alice in Chains enlisted various singers, including Heart’s Ann Wilson, for their set. “We just got up there and didn’t really realize, until we were standing there, that it was kind of a weird thing, playing those songs and just being together, doing that in public,” says Kinney. “But it was the best way to do that, because there was no thought [of a reunion] and it wasn’t about us.”

The following year, when Ann and Nancy Wilson were taping a concert for VH1, they asked if Alice in Chains would appear again. William DuVall was one of the vocalists who performed with the band on the Heart show; DuVall’s band Comes With the Fall also served as both backing band and opening act on Cantrell’s tour for his second solo album, Degradation Trip. DuVall’s voice was a good match with Cantrell’s harmonies—the key to the trademark Alice in Chains sound—and he was asked to jam with the group. By October 2008, the group had entered Dave Grohl’s Studio 606 in L.A. to begin work on the first new Alice in Chains album in 13 years.

One-off shows were one thing; resurrecting the Alice in Chains legacy was another.

“Layne’s death was such a deep, deep loss,” says Silver. “And there’s that question of, what do you do with a tragedy in life? Do we stop living? Or do we go on? Looking at the story that that record tells, and then the beautiful love letter that Jerry wrote to Layne to close the record [the title track], tells a very complete story. And it has been a really cathartic experience, and extremely healing. Extremely healing.”

There was no thought of using a different name. “It never even crossed our mind to change the name,” says Kinney. “We could call ourselves Leather Snake, go play our songs, and people would go, ‘The guys from Alice in Chains are playing the club down the street!’ They’d never be, like, ‘Hey! Leather Snake kicks ass!'” But he admits to expecting some flak from diehard fans. “I thought people would be a little more aggravated. And they were at the beginning. They’d be, like, ‘How dare you!’ and ‘You can’t!’ They showed up at shows with their arms crossed. But it’s been turning around.”

And a big reason for that, according to Kinney, is the chance to remind people which of Staley’s accomplishments are the ones worth celebrating. “I felt for the most part when Layne passed away he was a footnote, swept under the carpet—’Oh, another junkie dies,'” Kinney says. “That year we went to the Grammys again; we were nominated, and I think Susan convinced us to go. And we go there, and they played the video of all the people that have passed away that year, and they don’t even put him up there. I just stood up and walked out. I’m, like, ‘This is sickening.’

“But by doing this, Layne’s actually become more powerful now than he ever was. And I see it every night. We play and everybody’s singing songs that Layne sang. And at the end of the night they all had a good time.” Those redheaded stepchildren have finally been welcomed home.