Sleater-Kinney are on a merry-go-round.

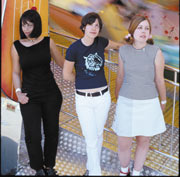

This isn’t intended as metaphor, or clever journalistic gambit. Corin Tucker, Carrie Brownstein, and Janet Weiss are, literally, straddling ponies, horses, and zebras as the mad-happy din of carousel music plays them round and round.

Dispatched to interview rock celebs, one assumes the circumstances of the meeting will fit the image of the artist; you’d hardly expect to go fly-fishing with Marilyn Manson, go thrifting with P-Diddy, or attend The Vagina Monologues with Eminem. Yet here we are—Sleater-Kinney and I—in the middle of a mirthful Oregon afternoon, enjoying all sorts of games, rides, and confections at Portland’s Oaks Amusement Park.

“Who wants cotton candy?”

It seems an almost impertinent question to ask a band oft-characterized as the self-serious, puritanically intense, chippy ideologues of indie rock.

And, besides, they want corn dogs.

It’s been two years since Sleater-Kinney’s last album, one year since Time magazine crowned them “America’s Best Rock Band.” If the recognition felt premature then, the impending release of One Beat makes it play like prophecy. The band’s sixth long player is a dark, sprawling opus, an inexorable rumble of song that outstrips its predecessors by a mile.

This isn’t the same group who sang “I Want to Be Your Joey Ramone.” It’s 2002: Joey Ramone is dead, the world’s on fire, and rock ‘n’ roll has to find a way to stay meaningful in a post-Sept. 11 world.

That’s a challenge few care to take on; certainly no one among the cute, color-coordinated, retro-rock brigade is up to meeting it. But S-K have elected to tackle the task—damn the consequences.

One Beat is so loaded with both political portent and guttural power you expect ivory tower academics and blue-haired punkettes alike to proclaim the record manna from the Northwest: rock’s salvation arriving in well-worn Riot Grrrl rags.

But fans and critics have always invested Sleater-Kinney with an inordinate amount of expectation, even if sales of all their albums combined are roughly equal to what ‘N Sync might move on a good afternoon. Until now, however, Sleater-Kinney’s aims were too limited for them to truly be worthy of inheriting the “only band that matters” mantle. Their music, similarly, didn’t warrant such distinction. For all the talk of their originality, they sometimes sounded like the pre-makeover Go-Gos, playing punk in ’79. Not the worst reference point ever, but certainly not the stuff of savior status.

One Beat changes all that, dramatically. By turns a dissident manifesto, protest album, polemic, and sweet ’60s soul kiss, it’s a record at last worthy of the breathless praise heaped on them these many years.

Arriving for the photo shoot and chat, Sleater-Kinney are a fastidiously styled bunch: Tucker, a cherub in pigtails and sailor stripes; the solemn, raven-haired Weiss in a sleek uniform of all black; the convivial Brownstein clad in sharp white slacks and navy blue tee.

You might wonder at this point what a man is doing interviewing them at all; don’t Sleater-Kinney have some standing policy about only talking to female reporters? Pure fiction, they insist. Indeed, much of the day is spent correcting the half-truths and outright lies spread about the band.

If certain segments of the media have been quick to canonize them, others have sought equally to marginalize their work; the press circa ’97’s Dig Me Out often barely mentioned the music, instead trawling for dirt on the band’s sexuality and personal lives.

Such reactions aren’t surprising. This is, after all, a group of unapologetically truculent and aggressive ladies—a band that shunned multiple major-label suitors to stay with its hometown indie. Behavior like that doesn’t go unpunished in an industry that prefers its women to be canny armchair liberationists—publicly assertive but docile in the boardroom.

Sleater-Kinney clearly relish their abrasive rep. Tucker likes to tell the story of one early show, where she so enraged the soundman that he shut off the P.A. mid-set. Brownstein happily recalls Bryant Gumbel’s on-air fit of pique—”Sleater who? Who is this band”—after reading the Time plaudits. And then there’s Weiss, once accosted by a hectoring Courtney Love, adamant that Sleater-Kinney were throwing it all away by not going for the big brass ring. Weiss informed the widow Cobain, in the most polite terms possible, that she should stick her notion of “success” and crawl back into her Hole.

“We’ve never allowed other people to trivialize what we’re doing,” says Tucker. Her tone suggests they’re not about to start anytime soon.

We are a conspicuous-looking crew: three grown women waiting to slide down a giant lapping tongue called “The Big Pink,” a 6-foot, tassel-haired photographer shadowing their every move, and me, standing guard over a heap of purses, bags, and jackets.

As Sleater-Kinney take turns plunging for the camera, a young father with a 5-year-old son in tow looks on curiously.

“So I gotta ask,” he finally says, turning to me, “are they a band or something?”

“Yeah, they’re called Sleater-Kinney.”

Abruptly forgetting that he’s surrounded by toddlers, the man unexpectedly explodes.

“Holy shit, I just bought their album last week! No fuckin’ way! Honey,” he says, flagging down his clearly embarrassed wife, “it’s fuckin’ Sleater-Kinney!”

The scene repeats itself several times over the course of the day (minus the corruption of the kiddies). Each time, the faces glinting recognition are different—first a teenaged boy, then a twentysomething woman, later a middle-aged couple—but the reaction is the same, a profuse mix of ohmigod awe and relief at the band’s geniality.

“We only get recognized when the three of us are together,” says Brownstein, somewhat abashed by all the fuss. “Yeah, normally I get people telling me, ‘You know, you look just like that girl from Sleater-Kinney,'” offers Tucker.

Still, few bands—regardless of fame, fortune, or SoundScan figures—have as profound and visceral a connection with their audience as Sleater-Kinney. In part, it was the pressure of such external expectations that fueled the creative direction of their last album, 2000’s All Hands on the Bad One.

After the cerebral, disquieting departure of ’99’s The Hot Rock, recorded with Roger Moutenot (Yo La Tengo, Freedy Johnston), the group reconnected with longtime producer John Goodmanson—who’d worked every other S-K record, as well as albums by Tucker’s and Brownstein’s previous bands—with the idea of getting back to basics.

“Thematically All Hands was about girls having fun playing and seeing rock music,” says Goodmanson, a gifted, amiable fellow, whose diverse credits include everything from local punks the Catheters to rap dynasty Wu Tang Clan. “It returned them to the kind of empowering, fun songs they’re so good at.”

All Hands was judged by many (and derided by some) as not nearly as ambitious or outr頡s its predecessor, an assessment that ignores the context in which it was released. Written and recorded in the aftermath of the rape and violence of Woodstock ’99, songs like “Ballad of a Ladyman” and “You’re No Rock ‘n’ Roll Fun” were intentionally simple, self- referential anthems intended as defiant rejoinders to the Neanderthal mook-rock generation of Limp Bizkit and Korn.

“It was more self-conscious in thinking about what it means to be women in rock ‘n’ roll,” says Brownstein. “We were railing against certain things that were going on but also trying to embrace and remind ourselves of what we loved about the band in the first place.

“I’m really fond of the songs that are on the record, but I think you can really only do that kind of thing once.”

While All Hands was a necessary and successful endeavor, the trio were conscious of falling into a creative trap, devolving into a caricature of themselves.

“Even though [All Hands] worked, afterwards I think we realized that we didn’t want to keep writing songs about being in a band and touring,” says Weiss. “We also knew we had to break things up musically as well.”

News of Tucker’s pregnancy in 2000 signaled a hiatus for S-K—a break the group decided to extend through the following year. Looking back, all three admit there was a degree of uncertainty about the decision—obvious concerns about losing the momentum and magic that had sustained them for so long.

But after five years and as many albums—a relentless half-decade of writing, recording, and touring— Sleater-Kinney decided to stop. Whether they would resume, and what it would sound like if they did, remained a mystery.

“All aboooooaaaaarrrrd!”

Corin Tucker is staring at a gaggle of children, laughing as they file onto Oaks Park’s kiddie train.

“This is a good place,” she smiles, thinking of her son, Marshall. “I can bring him here.”

It’s hard to imagine Tucker in the role of matriarch; so much childhood lingers in the soft round features of her own face. Yet for all of 2001, she did little but nurse and care for her firstborn with husband Lance Bangs, a respected music video director.

While Tucker held down the home front, Weiss was busy recording and touring with Quasi, the longtime duo she’s maintained with her ex-husband, multi-instrumentalist Sam Coomes. The group’s The Sword of God album, released last summer, was an especially accomplished affair. Brimming with a cockeyed sensibility and cocksure musicianship, the disc evinced Weiss’ growing talents as both an artist and a producer. (“Janet is getting really good at making records,” says Goodmanson. “It’s kinda scary—pretty soon they’re going to be self-sufficient and not need me at all.”)

Brownstein, meanwhile, stayed busy on a number of nonmusical fronts, acting in an independent film, working on a research project with her college mentor, and even doing a bit of substitute teaching.

In retrospect, the guitarist sees the layoff as a crucial respite in helping the band members gain a renewed sense of self—something easily lost within the insular bubble of a successful band.

“It’s pretty scary when your identity is wrapped up in something like a rock group,” she muses. “From my own perspective, I’m more than just a member of Sleater-Kinney. But to people in the outside world, that’s often how you’re identified, and sometimes it’s hard to shake that definition of who you are. And it can start to affect your creativity.

“During the time off, there was a certain kind of psychological and emotional journey that happened for all us that was really important for the band to continue.”

Equally important was Brownstein’s decision to relocate from Olympia and join Tucker and Weiss in Portland. Ensconced in the same city for the first time in years, a proximate sense of creative camaraderie—something borne out on the new disc—was restored to the group.

“And, naturally, having taken a year off, we were ready to start playing again,” says Weiss. “Just to hang out and be together. It wasn’t just that we were living in the same city, but that we all realized how much we needed each other and how much we needed the band.”

The trio hashed out plans to rededicate themselves to S-K in 2002, beginning by devoting several months—an unusually long stretch for the group—to writing and preproduction on what would be their sixth album.

“In a lot of ways when you write a record, where you are in your life, what’s going on the world, it all comes out,” says Tucker. “So there’s a lot of serendipity involved.”

Serendipity came in the form of a billowing black cloud on the morning of Sept. 11.

“7:30 a.m., nurse the baby on the couch/Then the phone rings, ‘Turn on the TV,'” begins “Far Away,” Tucker’s harrowing narrative of her own Sept. 11 experience, an event that left her with a profound sense of her own motherhood.

“It’s one thing when you’re worried about your own life, but when you’re worried about your kid’s life, it becomes something else entirely,” she says, taking a long pause. “And you start wondering . . . what kind of future is waiting for him?”

Reacting both to the tragedy and the surge of star-spangled xenophobia that followed in its wake, the band began crafting songs with a tacit understanding that the new material would be an unflinching, headlong dive into topical political territory.

History has been unkind to such earnest and willful sentiment in rock ‘n’ roll—consider the knocks other overtly politicized acts, from the MC5 to the Clash, have endured over time. But Tucker, for her part, was unconcerned.

“If I thought about it like that, I’d never write anything,” she says. “I mean, how could you not have an opinion about all that’s happening? It would almost be bizarre if we didn’t have a broader political sense on this record.”

“Plus,” adds Tucker, “I’m in a unique position. There’s not that many housewives and mothers writing about Sept. 11, at least in a way that’s critical of Bush”—criticism she levels with virulent imagery like, “And the President hides /While working men rush in, to give their lives.”

Fueling a second, equally strident set of songs was Brownstein. As to the inspiration for the crushing betrayals and romantic alienation detailed in cuts like “O2” and “Funeral Song,” she demurs. “They’re, um, inspired by very personal things, so I’m a little reticent to talk about them.

“But the common thread with all the songs on this record is that they’re exploring the theme of faithlessness. It’s really all about trying to uncover some hope or meaning in a time that’s very, very bleak.”

The afternoon has started to wear, the combination of summer heat and junk food producing a sleep-inducing cocktail. Sleater-Kinney, however, perk themselves up for the task at hand, striking poses in front of a whiplash Tilt-A-Whirl called, appropriately enough, “The Rock ‘n’ Roll Ride.” Above them is a Mount Rushmore of music icons: the painted faces of Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Bruce Springsteen and . . . Trey Anastasio. This is tie-dyed, Phish-friendly Portland, after all.

This spring, having navigated the twin extremes of their last two albums and spent a year freeing themselves from nagging external expectation, Sleater-Kinney were ready to indulge whatever whims suited them and their new songs best. Goodmanson, by now an extension of the band, was again drafted to produce, with both parties looking to push each other into heretofore-unexplored stylistic territory.

To aid in this, a sundry cast of collaborators was recruited for the sessions. Northwest sound supremo Steve Fisk was corralled to add some splashes of color, leavening the songs with a new-wave sensibility: Cars-inspired keyboards and bubbly synth squiggles. Cellist Brent Arnold and violinist Jen Charowhas—veterans of various regional rock projects including the Walkabouts and 764-Hero—scored strings, while ample blasts of brass were supplied by saxophonist Mike Wayland and trumpeter Russ Scott. Weiss’ ex, Sam Coomes, provided theremin on one track, while for “Prisstina”—the story of a straight-arrow bent by rock ‘n’ roll—Hedwig and the Angry Inch composer Stephen Trask was brought in to add a bit of vocal decadence.

Mostly, though, it’s the efforts of the band’s three principals that shape the manifold musical directions of the 12-song platter. Particularly crucial is the intuitive interplay of Brownstein’s and Tucker’s guitars, which reveals new depth throughout. And, of course, the work of Weiss—”Keith Moon 2002,” enthuses Goodmanson—whose scything percussion makes even relatively minor material like “Light Rail Coyote” and “Hollywood Ending” bristle with energy.

“They’re not session players or virtuosos,” says Goodmanson, “But they’ve developed what they have together—which is a special thing. The way the three of them combine is really potent in a way that’s hard to pinpoint or even describe.”

Opening with a jarring duo of corrosive cuts—a sequence intended as both a statement and challenge to listeners— the rest of the album yields to a series of cleverly absorbed genre exercises.

“On something like ‘Combat Rock’, for example,” says Brownstein of one lumpen anthem, “we were thinking, ‘Let’s write a reggae song.'” By the time they’re through giving the tune a terse, angular makeover, even the intended Lee Perry homage ends up sounding singularly like a Sleater-Kinney song.

Elsewhere, S-K indulge their classic-rock streak—the band often cover old CCR and Jefferson Airplane songs in concert—with the Doors-y drone of “The Remainder” and the bouncy Motown shuffle of “Step Aside,” a dance floor call-out with a conscience.

Here, Tucker sings storming lead in a voice far removed from her signature high-register hiccup. “I wanted to sound like LuLu on that one,” she says of the track, but ends up coming off more like Martha Reeves, while Brownstein and Weiss offer their best Vandellas backup.

“This mama works ’til her back is sore/But the baby’s fed and the tunes are pure,” belts Tucker, carving sweat-soaked filigrees into the song and proving she’s nothing if not a soul singer in the best, broadest sense of the word.

The album’s standout, however, is another old-school inspiration. “I have a lot of things lodged in my brain from my teenage years,” laughs Tucker. “They sorta get dredged up whenever I try and write.” One of those things triggering a synapse was the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” which inspires both the title and tenor of the album-closing “Sympathy.”

Utilizing a whole host of Stones aphorisms—slide guitar opening, funky cowbell, sotto voice backing—Tucker fashions a haunting blues, written as a prayer for the survival of her prematurely born baby. Against Brownstein’s dirty, churning, Keef-nicked riffs, Tucker’s tortured howl (“I’ve got this curse in my hands/All I touch fades to black”) leads to a Herculean breakdown that surely ranks as one of the most explosive moments in the band’s catalog.

“To me,” offers Goodmanson of One Beat, “it’s not a record that’s built for alternative radio. Yet, surprisingly, the reaction from everyone I’ve played it for has been like, ‘Wow, these guys are really going for it.'”

Indeed, the current landscape of rock radio—dramatically altered in the past year by the likes of Ryan Adams, the Strokes, and White Stripes—seems the most welcoming in years for an act like Sleater-Kinney.

The band’s label head, Kill Rock Stars owner Slim Moon, isn’t so sure. “When the last two records came out, the powers that be at radio said, ‘We can’t play this because there’s no bass, there’s no bottom end.’ And now they’re playing the White Stripes,” he notes of the similarly bassless combo. “But the other thing they always say is, ‘Well, we already have a ‘female’ song in our rotation.’ So I don’t know if the rules have changed that much. I guess we’ll find out.”

“I don’t ever really imagine us with a place in the mainstream,” insists Weiss. “By a lot of the choices we’ve made, it’s sorta predestined for us not to become one of those bands. If we somehow did, I guess it’d be that much more of an accomplishment.”

Regardless of their commercial fate, Sleater-Kinney can rest easy with the creative triumph of One Beat—and in the fact that they’ve developed a core constituency of fans who are in it for the music.

“They’ve built that thing,” says Goodmanson, “where they make their own records, have complete creative control, and can play any city in America two nights in a row and sell out the venue. To me, that’s a perfect world. If they can keep that going —it’s a dream situation.”

“We don’t make tons of money. The goal of the band has never been about making money,” says Tucker. “We just want to be able to sustain ourselves and continue making music. Who knows what that means for the future.”

It appears to be a bright, expanding horizon, as the band’s mostly young female audience has, in recent years, grown to include more men and more adults. “I think they’re still reaching a lot of young people,” says Moon, “but I hear from a lot of older fans—people who’d given up on rock ‘n’ roll—who say the band has restored their faith in music.”

In retrospect, perhaps the amusement park setting does fit. From where they’re standing, Sleater-Kinney can get both the dizzying heights and the homey midway fare—a perfect balance of familiar pleasures and adrenaline-soaked risks.

And at last, they’re tall enough to ride.

Sleater-Kinney play the Capitol Hill Block Party main stage at 7:45 p.m. Sun., July 14.