The Pike Place Market is known far and wide as the crown jewel of the Emerald City. But how well do we really know this destination for tourists and home cooks? In this series we will explore the heart and soul of the Market—its people. The Market is more than its incredible fish, flowers, and produce–it’s a living, breathing village in the heart of downtown Seattle.

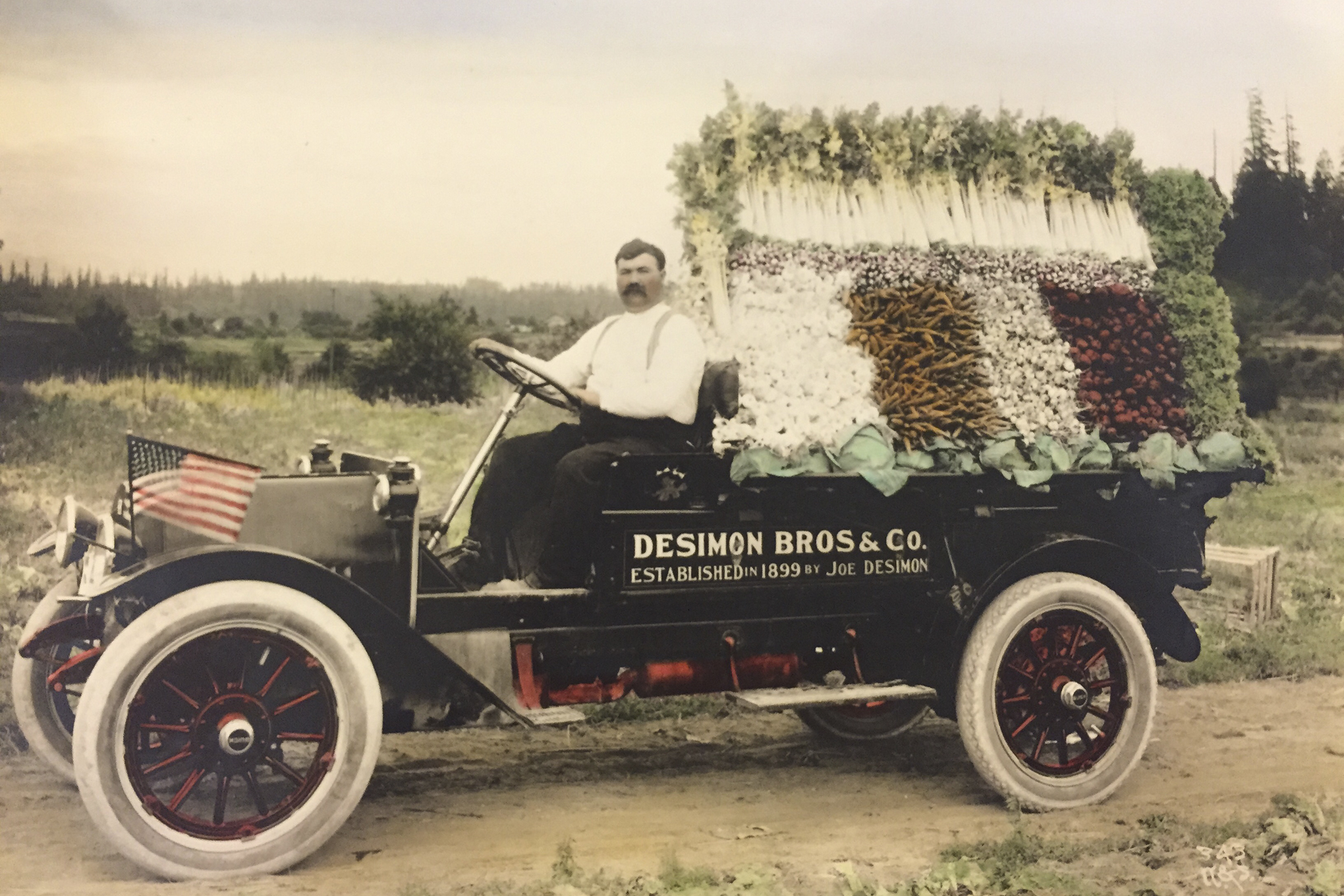

He was one of millions, says Joe Desimone, recalling the story of his grandfather, immigrant farmer Giuseppe “Joe” Desimone, who as a young man was a stowaway on a ship bound for Ellis Island.

Like the four million other Italians who arrived on U.S. shores between 1880 and 1920, Giuseppe came in search of opportunity. He thought he might find it in Seattle because he heard that vegetables grew like weeds and land was cheap. He was right. He bought some of that land, leveraged his assets, and took huge risks to succeed. Like so many others, he found a place for himself at the Pike Place Market and got to work.

The Market, Joe explains, was built on the backs of immigrants—from Japanese and Filipinos to Sephardic Jews and Italians. “They were people who came from a foreign country, with no language skills or formal education.”

When the Market was under threat during the Great Depression, Giuseppe bought out shares and kept it going, says Joe. And when people fell on hard times, Giuseppe would help them, taking in the children of fellow Italian immigrants who couldn’t afford to raise them. This goodwill was passed down, like an heirloom, from father to son. Once, when a boy became very ill with a brain disease and his parents had no money to cover health costs, Joe’s father, Richard Desimone, let the child’s father operate rent-free at the Market for two years until his son recovered. “Their philosophy was to help others because they knew firsthand how difficult it was,” Joe says. “My grandfather knew people who went to bed hungry. That’s why he had empathy for those having a difficult time.”

The Desimone family continued to offer a helping hand in good times and, especially, bad times for the Market. During World War II, one of the bad times, Joe’s own father kept rents low so that the farmers could afford to stay in business. “It feels special for me because if my family had not kept the rents low, had not worked with people in difficult times, there possibly would not have been a Market today,” he says. “It’s the oldest market in the United States—at least the oldest continuously operated that survived the last century’s innovations of refrigeration, grocery stores, and processed foods. I’m very proud of the fact that my grandfather and father took a real chance—and now Seattle has something that is the envy of the world. ‘Direct from producer to the consumer,’ it really is the hottest thing in food right now. You can’t go anywhere these days without hearing those words, even at places like Safeway.”

Today the Market continues to serve as a support and springboard for those in need. In addition to the opportunities provided to its many producers, the Pike Place Market Foundation supports a network of services in the Market that provide low-income housing, health care, healthy food, child care, and a community of support to our most vulnerable neighbors in downtown Seattle. “Nurses go out into the community and treat people who are shut-ins or give them bus tickets to come see the doctors,” says Joe.

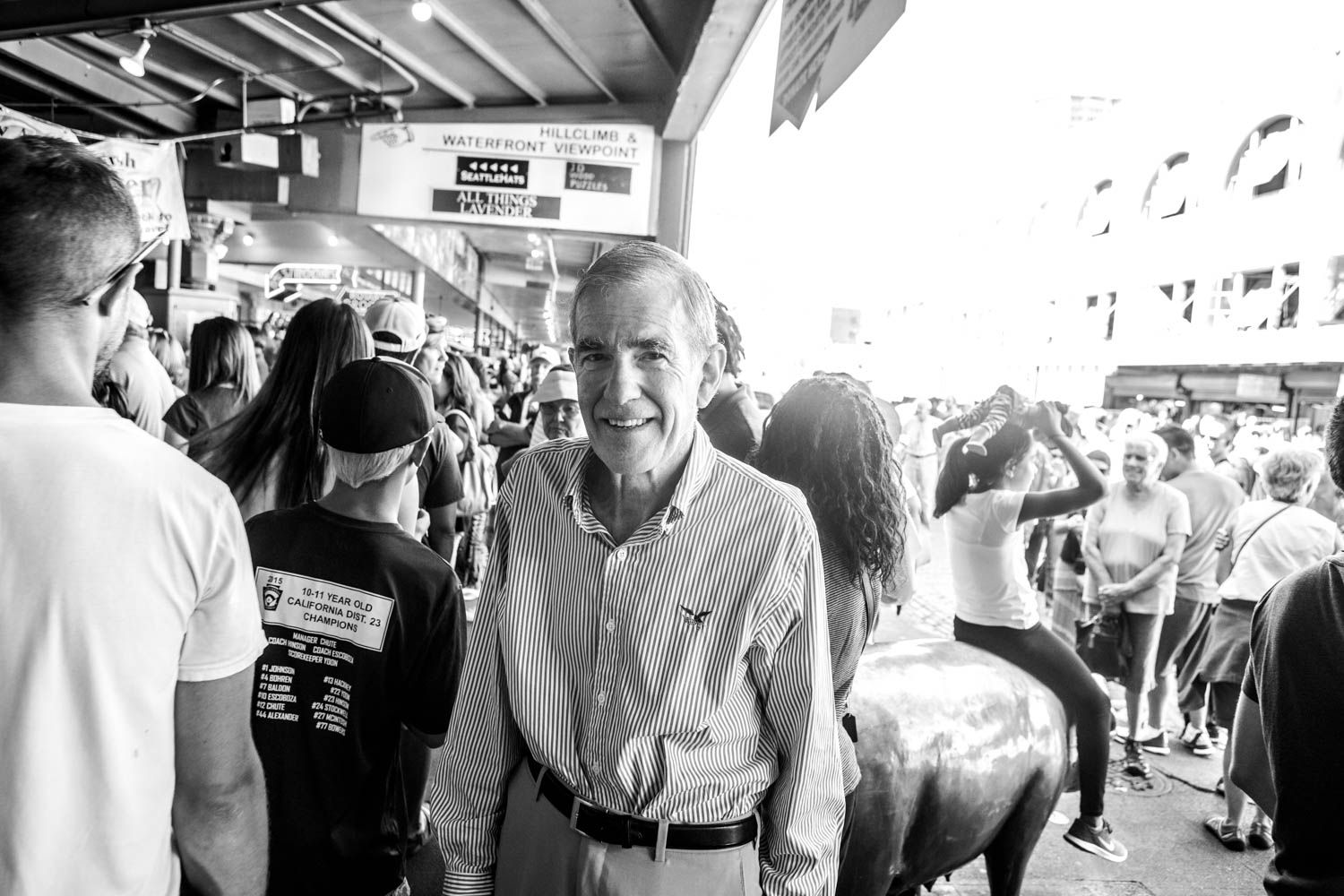

Looking down at the Market, Joe reflects: “There’s a certain energy here. They’ve kept the architectural flavor of the Market, the vibrancy and the diversity and number of people who come down here. My grandfather and my father would be thrilled if they saw the number of people down here shopping and enjoying the Market, particularly given all the sacrifices they made to keep it going. . . . There was never a guarantee that things wouldn’t go under.”

Joe is the keeper of many stories. One of the oldest came after the mayor announced the creation of a city market in 1907, taking business away from commission houses that acted as middlemen and controlled prices. The market would allow the immigrants, many of whom knew little more than farming, to sell directly to the producer. Joe tells a story about the first brave farmer who rode down the Market’s main thoroughfare, then just a dirt road, despite threats from the commission houses that they’d tip over his wagon or drive him out of business. As he came around the corner with his produce, people started to mob the wagon and throw in coins in exchange for the food. The word was out: The Market was viable! Today, the “Meet the Producer” sign atop a Market building testifies to that victory.

The repercussions of that momentous time are still felt in the success of the children of the Market. Like many immigrants at the time, Joe’s grandmother couldn’t read or write, and his grandfather had the equivalent of a second-grade education, but a lot of street smarts. Through the Market, immigrant families were able to keep their kids in high school, and a lot of the children then became bookkeepers for the family business. “The Market became a real incubator because they were able to not just work down there, but save and go on to become the doctors and nurses, engineers and politicians,” Joe says. “Others started their own businesses. A lot of people got their first training here at the Market.”

Studying an old photo of his grandfather, with his pronounced handlebar mustache, Joe shares the important lessons that one generation can learn while watching their parents help the less-fortunate. And how the Market creates a space for that to happen by bringing all kinds of people together. “Down here,” Joe says, “everyone can feel comfortable. It doesn’t really matter if you’re down on your luck and living on the streets or subsidized housing or if you drive a Ferrari and wear an Armani suit … it’s one of the few places where everyone can be part of a community. It’s this really wonderful inclusive place, and I hope it can continue for another 100 years.”