We asked author and critic Ruth Reichl to share her thoughts on Angelo Pellegrini, for whom the Pellegrini Award is named.

When I was in college in the mid-’60s, I spent my spare time in a thrift shop called Treasure Mart, looking for old cookbooks. It was before most Americans had any interest in cooking, so I always left with my arms full.

The store kept piles of old magazines by the cash register, and while I was waiting to pay I usually pawed through them. One day, flipping through an ancient issue of Sunset, I was startled to discover a recipe for pesto sauce. I turned to the cover to look at the date: 1946. This was shocking; even then, in 1966, basil was an incredibly exotic herb. Yet this magazine, which was older than I was, offered instructions for turning it into a green sauce for spaghetti.

Years later I would discover that this was the first published pesto recipe in America. But at the time, all I wanted to know was who the strange person who had written the article might be. It turned out to be a man named Angelo Pellegrini, and I wanted to know more about him. I went right back to the bookshelf, unearthed a stained copy of An Unprejudiced Palate—and found that my life had changed.

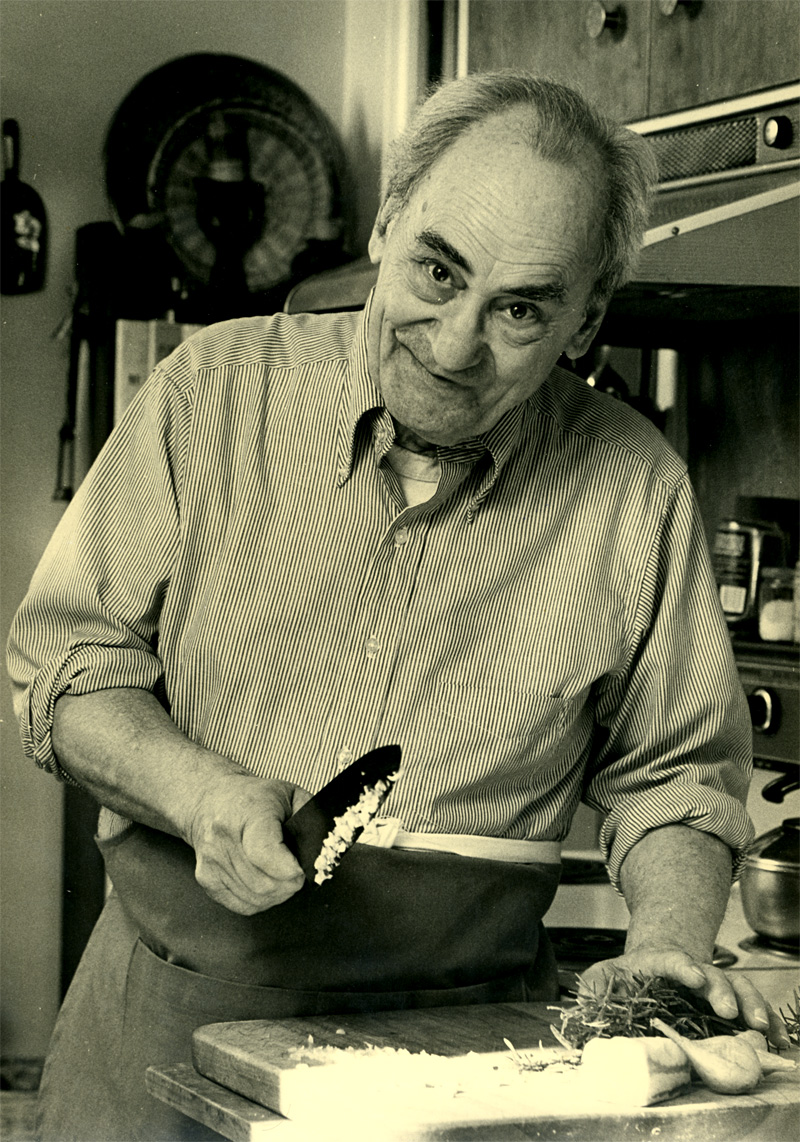

Pellegrini’s book was not a cookbook in any ordinary sense. It was a manifesto for living the good life. Pellegrini had emigrated from Italy at age 10, but, unlike so many immigrants, he cherished his roots. Although he turned himself into an English professor, in his heart he was a peasant. During the day he taught Shakespeare, but at home he gardened, fished, and cooked in a wood-burning oven. He believed, passionately, that eating well was important. And in the time of TV dinners, Pellegrini’s notions of how to do so were distinctly out of step with the rest of the world’s.

Pellegrini believed in growing your own food, eating with the seasons, using your senses, and taking advantage of the bounty all around you. He ripped out his lawn and put in a garden. He ate nose to tail. He even made his own wine (with grapes supplied by his friend Robert Mondavi). His was a great voice—but it was about 70 years ahead of its time.

It was a slow-food voice in a fast-food nation, but it did not go entirely unheard. Pellegrini’s books—like The Food Lover’s Garden; Lean Years, Happy Years; Wine and the Good Life; and The Unprejudiced Palate—developed a cult following, and had a profound effect on people like Alice Waters, Paula Wolfert, and myself. Pellegrini believed that Americans would be the best cooks in the world if they only paid attention to the abundance all around them. He not only predicted the changes that would come, he helped make them happen.

Seattle Weekly is very wise to honor the memory of this native son by establishing the Pellegrini Award, given annually to someone following in Pellegrini’s very large footsteps. This year’s winner, Chris Curtis, single-handedly started Seattle’s Neighborhood Farmers Market Alliance, which encourages everyone to eat the kind of fresh, local food that Pellegrini wanted us all to eat.

By all accounts, Angelo Pellegrini was an extremely unpretentious man. Although he was a perennial judge at the Los Angeles County fair, he once told a friend that when it came to wine, he took his grandmother’s advice. “Wink,” she told him, “if you like it.”

Wherever Angelo Pellegrini is right now, I’m sure he’s winking.