Chocolate is everywhere, and seldom more so than this year. Tim Burton is set to release his Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, with Johnny Depp playing Willy Wonka, and this week is Valentine’s Day, which means the stuff is especially rampant right now. But where I’m standing, chocolate really is everywhere—for example, at the moment, it’s stuck between a revolving metal grate and a conveyor belt meant to catch it.

“Here,” says Todd Kluger, as he uses his fingertip to nudge the inch-big square of mint ganache back onto the conveyor belt. “The ones in the middle get caught there a lot.” A little lopsided, the confection tumbles back onto its path. It’ll be a reject, one of a small handful today. Were I merely observing, I’d probably grab the unsellable truffle for myself. Instead, I’m learning how to make them.

This is not exactly new terrain for me. Before turning to writing full time, I spent several years working in kitchens, a couple of them at an ice creamery where my primary job was to make ice cream, cones, and cookies. It’s been a few years since I’ve stepped into a confectioners’ kitchen, and I’m here to write a story, not meet a food-production quota. But it’s easy to remember what attracted me to this kind of work before, starting with Kluger, who’s a convivial guy, and his boom box, which is currently tuned to KEXP. Next to it is a small stack of CDs. Mmmm—a job where I could listen to music all day long without disturbing my colleagues. Sigh.

Todd Kluger, the 36-year-old co-proprietor of the Chocolate Company, with his hard-won cocoa-bean grinder. (Pete Kuhns) Todd Kluger, the 36-year-old co-proprietor of the Chocolate Company, with his hard-won cocoa-bean grinder. (Pete Kuhns) |

Kluger, who’s 36, co-runs the Chocolate Company, an offshoot of Seattle’s Essential Baking Company. Two years ago, Kluger and his partners, EBC founders Joseph Whinney and Jeff Fairhall, began selling chocolate confections that, like Essential’s baked goods, emphasize fresh, organic ingredients. Now, the Chocolate Company plans to get even more ambitious. In a few months, around late summer or early fall, the three partners will begin to manufacture their own chocolate.

This is almost unheard of, and not just in Seattle. Though the Northwest has long had a history of confectioners—Brown & Haley of Mountain Bars and Almond Roca fame is based in Tacoma, while Fran’s and Dilettante are both based here—only a handful of companies grind their own cocoa beans in the United States, and among them, the competition is ferocious. The major players, most prominently the privately held Mars and publicly traded Hershey, have garnered plenty of lore—anyone who thinks the idea of chocolate spies is something Roald Dahl made up for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory‘s benefit need only skim Joël Glenn Brenner’s 1999 book, The Emperors of Chocolate, which details the long-running feuds between Mars and Hershey, who between them produce most of the chocolate in this country.

Kluger and his associates aren’t planning to overtake Mars or Hershey. Their methods preclude it. Right now, the Chocolate Company eschews the use of extra sugar (beyond what’s already in the chocolate they currently purchase to make the sweets), corn syrup, or alcohol, all of which are used by larger chocolate manufacturers to ensure longer salability. As a result, the truffles that Kluger and I are making have a two-week shelf life. When the Chocolate Company moves into making its own chocolate, the sugar level will drop even further.

“I was turned on by the artisanal chocolate being made by Maison du Chocolat in France,” Kluger says. “My eyes were opened, as were [those of] a lot of other people in the U.S.—they used fresh ingredients. Not everything had to be stabilized with sugars and alcohol. There’s no reason to say anything bad about other companies. They’re good at what they do; I like a lot of mainstream chocolate. But Jeff had been an enthusiast of organic ingredients with the bakery, and Joe had chocolate experience.”

So did Kluger, a fourth-generation Seattleite and a former marketer for Starbucks. Kluger attended Washington State and Tokyo University, studying filmmaking, “which is how most careers start—in other directions,” he says. As a Starbucks brand manager, he was “really [taught] to be an entrepreneur, that the sky’s the limit.” His “horrible sweet tooth” (he cites a particular fondness for Snickers, caramels, Mountain Bars, and Mexican chocolate) led him to dabbling in chocolate and to France, Japan, and Costa Rica to study it. After leaving Starbucks in 2001 and a brief Bay Area dot-com sojourn, Kluger moved back to town, joined Essential, and began helping shape their chocolates line.

Straining mint leaves from the cream sauce (Pete Kuhns) Straining mint leaves from the cream sauce (Pete Kuhns) |

Kluger and I are making mint ganache, a basic filling and one of around 30 he makes regularly. He’s an enthusiastic and efficient trainer; the kitchen—part of the former Redhook Ale brewery at North 34th Street and Phinney Avenue North—is cavernous and tidy.

First we heat honey and cream together. I stir it until it comes to a boil; the mixture smells like Malt-O-Meal. We take it off the heat and add a giant fistful of washed mint leaves; these were picked yesterday, and most of the stem is still on them. “The stem has a lot of flavor, and that’s what we want,” says Kluger. We bring that to another boil, turn the heat off, cover the pot with plastic wrap, and let it sit, so that the mint can steep.

When we unwrap it a half-hour later, I’m expecting the liquid to have a greenish tint, but it looks more like cream of spinach soup, yellow dotted with leaf mulch. I help Kluger strain the mint leaves out, then fold a melted milk- and dark-chocolate combo—around half the volume of the cream, to my eye—into the mixture. Once everything is combined, the mixture’s ready to be tempered, which is done on a large, cold marble table in the middle of the room. We pour it into a rectangular blob and, with a sterilized cement scraper (purchased, Kluger wryly notes, at Home Depot) and flattening spatula, draw the edges to the middle, as the mixture cools and thickens.

After about five rounds of scrapes, the ganache has coagulated to a cake-frosting consistency. Earlier—right when I got to the commissary, in fact—Kluger had me paint a thin layer of chocolate on parchment paper in a cookie sheet. Now he places a metal frame on it, and this is where we put the fudgelike filling, one glob at a time, using the scraper. Once it’s all in there, he takes a thin, 2-foot-long scraper and drags it down the frame, leveling the top but leaving a few pockets. He fills those in with the excess and repeats the process. None of this is hurried—maybe because Kluger is being patient with the reporter and the photographer in the room (he happily slows his pace on a few steps of the cooking and enrobing to accommodate picture taking), but also because he exudes a quiet relish for working on the food’s timetable rather than his own. The man clearly gets a kick out of making this stuff again and again, day after day.

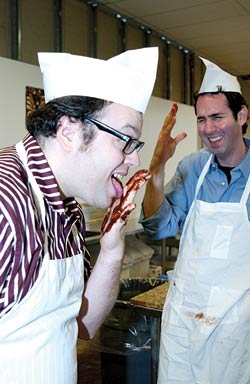

The author catches a row of mint ganache from the chocolate enrober. (Pete Kuhns) The author catches a row of mint ganache from the chocolate enrober. (Pete Kuhns) |

The one part of the confection-making process we skip is the cutting—the framed filling needs 24 hours to cool before it goes into a guitar, a wire-stringed implement so named for exactly the reason you think it is. (“It’s used for making [traditional] chitarra pasta,” Kluger notes.) Once the pieces are cut, they go into the enrober, a conveyor-belt device that covers the top and sides of the filling with a layer of chocolate via a self-generating waterfall. (The brushed sheet of chocolate coats the bottom.)

Kluger places the sweets in rows of five (four after a couple of the middle pieces begin catching on the belt); once they’ve been enrobed, I place a rectangular textured transfer sheet on top of the rows, patting them down a little bit to flatten the tops for packaging and visual appeal. The chocolates then pass through a cooling tunnel, about 15 feet long; they take six minutes to come out the other side, into a refrigerated room. “You can have some real I Love Lucy moments with this thing,” Kluger says, though happily, that evades us today. In the other room, I catch the rows of confections on a rubber scraper (transfer sheet side down) and move them onto more cookie sheets. Here they’ll sit for another 24 hours until they’re ready to be packaged and sold.

The warehouse space attached to the commissary is less than 40 feet from where Kluger regularly dumps mint into cream, but the two look like they belong in different scenarios. The kitchen may house a cool-looking long, streamlined conveyor belt, but that has nothing on the enormous round red thing in the warehouse that looks like a mechanical beetle from an old sci-fi movie—and indeed, the machine is nearly 70 years old. It’s the roaster that the Chocolate Company will be using to process cocoa beans. And it was not easy to find.

“We had to go out and find equipment from different parts of the world,” Kluger says. “The roaster was manufactured in Germany in 1936, but was in the U.S. with another manufacturer. There are distributors who buy and sell manufacturing equipment; most of them are giant, industrial machines. We’ve had to hunt around through our various contacts to find the equipment.” He laughs. “If only they sold those things on eBay.”

Kluger feels that the company’s plan to make its own chocolate has “closed the loop” between its organic-first principles and its forays into the confections market. And he feels they’re not alone. “In France and Japan, confections are about presentation and fresh ingredients, and not about a long shelf life. France and Japan were at the forefront of artisanal chocolates, and there will be other artisanal chocolate makers everywhere [in the U.S.]—it’s very tough to make them nationwide. Chocolate candy is a $17 billion a year industry, and gourmet chocolate is a five-year phenomenon, mostly in New York and San Francisco.”

He also says that the Chocolate Company aims to keep costs level with what they are now once it begins making chocolate. “We wouldn’t want to be making it for more money than we’re already buying [premade chocolate] for. We’re making it strictly for ourselves. The really good beans are hard to find.”

Needless to say, Kluger has an interesting view of the busiest holiday of his year. “If you’re an average-looking guy like me, being in the chocolate business definitely increases peoples’ interest. I’ve met a couple of women who’ve been more interested in the fact that I make chocolate than in me. But that’s a fun position to be in, because making chocolate is fun. We’re making candy here, not guns.”

The Chocolate Company’s wares are available at the Essential Baking Company’s outlets at 2719 E. Madison St., 206-328-0078, and 1604 N. 34th St., 206-545-0444; PCCs in Fremont (600 N. 34th St., 206-632-6811), Green Lake (7504 Aurora Ave. N., 206-525-3586), Kirkland (10718 N.E. 68th St., 425-828-4622), Issaquah (1810 12th Ave. N.W., 425-369-1222), Seward Park (5041 Wilson Ave. S., 206-723-2720), View Ridge (6514 40th Ave. N.E., 206-526-7661), and West Seattle (2749 California Ave. S.W., 206-937-8481); and Whole Foods in Seattle (1026 N.E. 64th St., 206-985-1500) and Bellevue (888 116th Ave. N.E., 425-462-1400).