BRASA 2107 Third, 728-4220 dinner every night

Once upon a time, chefs were men trained in French, German, or Swiss hotel schools—abusive environments in which apprentices learned to dodge flying knives while being harangued, humiliated, scapegoated, and forced to eat their mistakes. And as the abused tend to grow up to be abusers, these victims went on to perpetrate the cycle. This hierarchal crap and its corresponding gender discrimination still exist in Europe, as well as in New York, where the haute chefs tend to be fresher off the boat from Lyon or Hamburg. But mostly kitchens are run more cooperatively these days—people are treated like humans, and there are even (gasp) women. Seattle pioneered the hiring and promotion of women chefs in the 1980s.

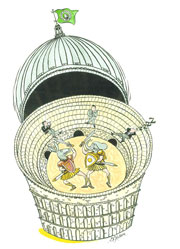

Tamara Murphy, chef and co-owner of Belltown’s Brasa, exemplifies how a chef of the new order trains her underlings more humanely—she’s showcasing them by presenting a menu with courses created by each of her seven cooks ($55 per person, Fridays and Saturdays in July). Murphy’s a transplanted New Yorker who got her Seattle chops at the late, legendary Dominique’s and the venerable Campagne; she’s included in Food & Wine’s latest “Selective Guide to America’s Superchefs.” And behind every name chef—Batali, Keller, Trotter, or Boyardee—there’s a squadron entrusted to reproduce the work of the maestro or maestra, day in and day out. As Murphy says, “The chef’s the conductor, who puts it all together; then there’s the violinist who’s actually doing the playing. These people do their different parts to make a piece come out right.” A huge part of being a great chef is assembling, training, nurturing, and retaining a team of cooks.

Murphy charged her team with creating dishes related to their backgrounds, in a conscious cultivation of the heart-based connection to food that great cooks need to become great chefs. It’s both a challenge and a vote of confidence; as Murphy says, “My cooks make me look good.” Here’s who she’s talking about, listed in order of the course each one’s making for the July menu.

Pedro Cruz, 25 (not pictured), is from Oaxaca. He followed sous-chef Marc Allen from Chandler’s and Stars. His first-course offering is a cool gazpacho ($5), a m鬡nge of hand-chopped Technicolor peppers, celery, cucumbers, carrots, and fennel. The soup has a slight vinegar twang, good olive oil, the racy earthiness of cumin, the sweetness of plum tomatoes, and the subtle heat of Fresno chiles.

Ron Anderson, 26 (top right), comes from the guns-and-orchard culture of Wenatchee. He honors that not by shooting something but by putting stone fruit on a plate. His offering is wood-fired apricot halves with Cabrales (the Mexican blue cheese), a patch of lean, dry-crisped, house-cured bacon, and a reduced balsamic glaze ($7). Murphy describes how she and Anderson got there. “I make these musical analogies, like high and low notes when you build a plate. I said, ‘What’s your highest note?’ Ron said, ‘It’s the balsamic.’ He was right, it’s the one that goes ting! up at the top. Then it’s the salty Cabrales, then the bacon, and, under that, the apricot. If everything is up at the high end, your palate just goes AAAAAAH!!!”

Julie Hawkinson, 35 (lower center), is chef de cuisine, second to Murphy. She’s a veteran of San Francisco megachef Jeremiah Tower’s glamorous, doomed Seattle outpost of Stars. Sausages are one of Hawkinson’s passions and a staple of her beer-and-brats Minnesota upbringing. Her plate has a spicy Mexican chorizo and a Swedish potato sausage, both poached in cider then grilled golden with a mustard glaze. There’s a pile of lightly dressed fris饠and endive, and a warm potato salad with sherry vinegar and golden balsamic ($9). It’s a glorious junction of Sonora, Scandinavia, and good ol’ American barbecue. It works the fingerboard of the tongue like Jimi Hendrix.

Andrew Murray, 23 (upper left), is from Boulder, but his parents are Colombian. He went to the California Culinary Academy in San Francisco. He worked briefly at the Palace Kitchen, then at the short-lived Falling Waters, and then found Brasa. For his plate, with a nod south to equatorial forests, Murray wraps long, narrow slices of plantain around a ring mold, then fries it crisp, making a shape like a coiled gold bangle. He sets it on its end, then fills it with mashed ripe plantain and roasted shallots, sprinkled with hot smoked paprika. Across the top lies a seared fillet of black sea bass with roast fennel tapenade and orange zest ($13).

Marc Allen, 28 (upper center), hails from Grand Rapids; he’s worked at Dahlia Lounge, Chandler’s, and Stars. True to his Midwestern roots, he pan-sears Yakima lamb chops with a mustard crust medium rare ($18), tender as a mother’s love. His garlic jus, which would be a controlled substance in many states, is shiny and rich without being too salty. There’s a browned timbale of savory bread pudding, sweet with Walla Walla onions, waftings of cinnamon and nutmeg, and broiled black mission fig halves with golden balsamic.

Mei-Lin Kong, 28 (lower left), has a large red and blue symbol from the I Ching tattooed on the crown of her short-cropped head like a cosmic yarmulke. She’s Malayan Chinese from L.A. but came more recently from Allen Wong’s, a Hawaiian regional restaurant in Honolulu. She calls her course a traditional warm Greek salad ($8), though it isn’t traditional and it isn’t Greek. Composed on a white plate is a ball of mixed goat cheese and feta with a perfect circle of paprika, red on white like a Japanese flag. There’s grilled endive and a roasted shallot, deep green poblano coulis, squiggles of kalamata tapenade, a tomato petal, and a little heap of cucumber watercress salad.

Julie Ogle, 22 (lower right), is Brasa’s pastry chef. She’s from Napa; she attended the California Culinary Academy and also worked at Allen Wong’s. Her dessert is an amazingly blond bourbon cake ($8), crusty and brown outside a soft and fine-crumbed inside. It’s served with a little oval of mint julep ice cream and scrawls of minty chocolate. It’s inspired by the baking of her Napa Valley grandma and great-grandma, and it’s wonderful.