As the city continues its relentless expansion, restaurants are keeping pace. A growing number of restaurateurs are opening their second, third, or fourth location, while some have hit double digits. Outsiders want in on the action too, as evidenced by the introduction of national and international chains such as Din Tai Fung, Little Sheep, Salt & Straw, and the soon-to-arrive Shake Shack. But with this breakneck speed of growth also come closures—even from heavy hitters. Josh Henderson has shuttered four restaurants this year; Brian Clevenger’s latest Italian spot on Capitol Hill lasted less than six months; and Maria Hines’ attempt to turn Golden Beetle into a trendy pub failed fast.

While new restaurants can be a sign of a thriving economy and a welcome addition to the city, there’s also the flip side to consider: As our stable of chefs are stretched thin to keep up with the uncharted growth, are we in danger of dissolving our own culinary landscape? And if restaurateurs merely follow investor money, blindly trying on new trendy concepts in the hope that they’ll stick, is that creating a real value for diners? And what is the price of resisting this growth?

These are questions I posed to three restaurant owners who have just one restaurant, with no immediate plans to grow—places I find particularly exceptional and exemplifying what I believe our city needs more of. These owners say that they plan to continue to improve their single location, providing the best possible experience they can for their clientele.

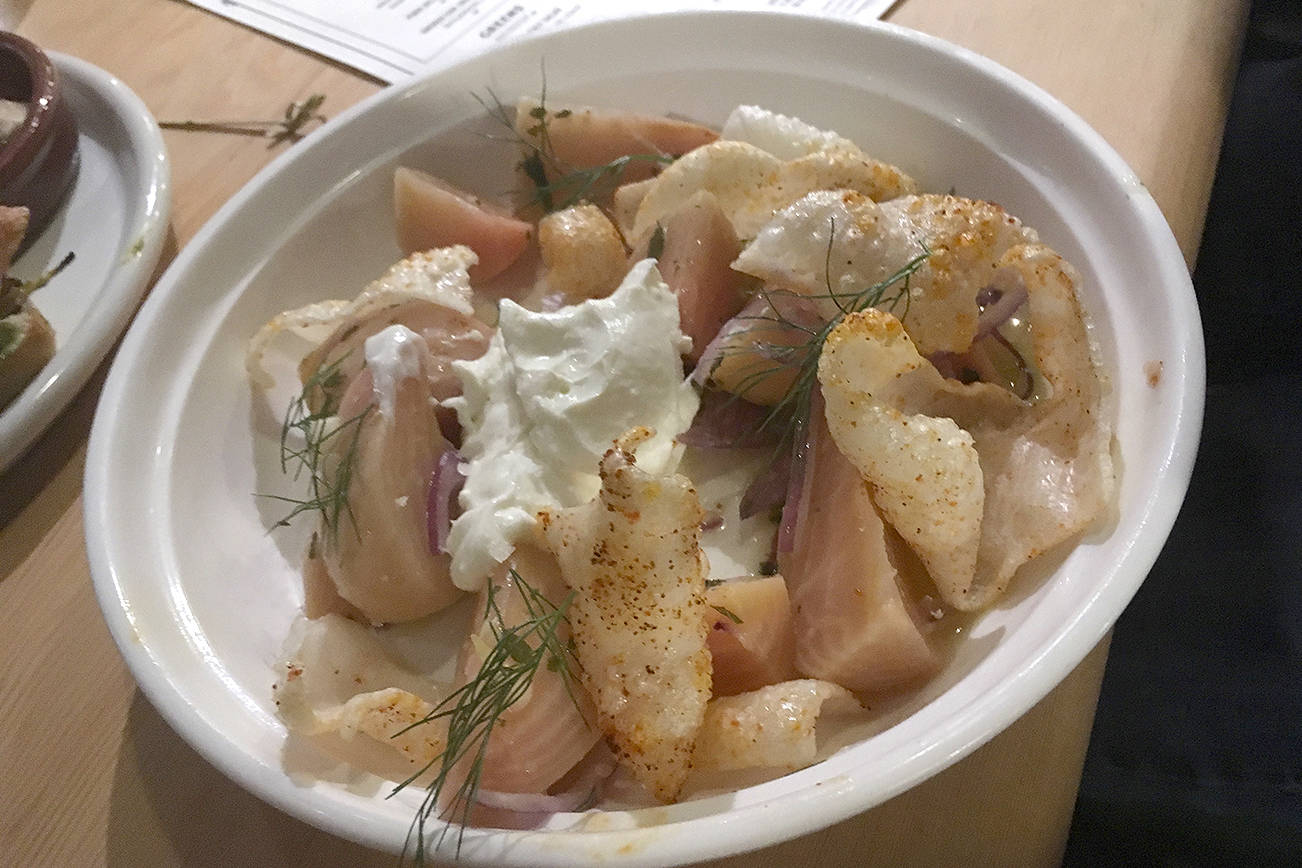

At Brimmer & Heeltap in Ballard, co-owner Jen Doak, a veteran of the Seattle restaurant industry, doesn’t sugarcoat the reality of owning just one spot. Though the inviting, quirkily designed restaurant with a tightly curated menu of Korean-accented Pacific Northwest ingredients is typically full and wins plenty of praise from the food press, she says that retaining good staff when the competition is so stiff is a constant challenge, and that the shifting landscape is such that, even four years in, they don’t have year-over-year financials to help them better assess their progress. They’ve had to scale back hours because of shortage of kitchen staff, while adding brunch and building out their back patio and private dining room to maximize profit. Things would be considerably easier if they had investors, says Doak, but giving up their vision and control is not something that she or co-owner and chef Mike Whisenhunt are willing to do.

She understands the lure, though. “I think that when a restaurant has investors and a lot of people getting paid out, another restaurant is an opportunity for financial gain,” she says. “Once you open a second and a third, that two or three percent of profitability is accumulated between multiple properties and it becomes much more. You then have more revenue to pay an enticing salary and benefits [to chefs and other staff].”

She doesn’t fault those who choose this path. “Ethan and Angela Stowell produce a great, consistent product. Tom Douglas and Matt Dillon are beneficial in so many ways.” Specifically, she credits them with using their resources to pave the way for others—for testing the market at locations in the city that don’t have many restaurants, for instance. It would be wrong, too, to understate the value in the creation of jobs for restaurant workers that these bigger players can offer, particularly when they’re able to provide things like health benefits.

But at the end of the day, for Doak it comes back to a book by lauded New York chef Danny Meyer, Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business. “He talks about how you’re going to have so many opportunities to morph your brand and that, when faced with them, you need to always ask yourself ‘Is this in keeping with the values and the principles I established with my initial brand?’ If the answer is no, it can’t even be considered. So if someone approaches us and says, ‘Hey, you can do more takeout and it’ll work’—well, we’re not about takeout.” That doesn’t mean they never adapt. “On the food side,” she admits, “Mike was so pissed to add bread to the menu. He didn’t want people to fill up before the meal, but he made it work within the confines of our brand, and it’s one of the most popular items on the menu.” (The bread is thick-cut, toasted to order, with changing toppings, and at brunch it gets a treatment of either cinnamon & sugar or peanut butter & jam.)

Making these sorts of necessary tweaks to the menu, optimizing their space, and trying to bring in revenue through more private events can be difficult, but Doak says she’s comforted by the natural rhythms that come when you’re fully present at one restaurant—knowing, for instance, that once school starts, people dine longer inside and drink more red wine. Then comes winter; after the summer flurry, the staff has more bandwidth, which allows them to get to know their clients better and do things like Sunday suppers. And while retaining chef talent will continue to be a challenge, she says they’ve never had a stronger culinary team. “I think the thing that will swing on our side is that cooks will have a little discernment to see that maybe it doesn’t pay to go to the flashy new object—that there’s a benefit in seeing that this restaurant has the legs to stand the test of time.”

Perfecte Rocher, the chef and owner at Tarsan i Jane in Fremont, agrees wholeheartedly with that sentiment. His team has taken over a year to build, particularly because of the restaurant’s multicourse, rotating menu of Valencian cuisine, which requires servers who truly understand the ingredients and techniques and can smartly speak to them with guests. “It’s hard to find people in Seattle because big companies are paying more than a smaller restaurant can. But we think we have a passion project that a big company can’t sustain. It’s difficult to have more places because it takes time to create this ‘family.’ If you want to focus on people, you want to make your own team, not just hire a couple of robots. The people we have now are solid and want to learn.” But he concedes that there are nights when business is slow and he has to send servers home—and that this is the only way to survive in fine dining without investor money. “We try to be honest with them and let them know that if they want to leave, that’s OK.”

Rocher isn’t a fan of the empire-building model. He thinks that rapid-fire openings create no education for the city, no appreciation for what is good and what isn’t—but instead aim to do simple things to please everybody. He rightfully points to some of the country’s most revered chefs, those who have achieved celebrity status: Thomas Keller, Alice Waters, Daniel Boulud, Jean-Georges Vongerichten. While most now have multiple restaurants, they stuck with only one for 15 to 20 years. “When you want a good restaurant, you need to spend a decade to make people love it. After that, so many employees have passed through your restaurant, so you can open another because you have a good pool of people.”

On his desire to stick to one establishment, Rocher says, “It’s difficult to have a restaurant like we try to do. We don’t have time to open other concepts. We improve slowly and try to make the best restaurant based on our vision. We tell our team that if you want to be here, that’s our goal.”

Rocher faces obstacles not only because of his high-concept restaurant, but also by being an outsider; a native of Spain, he moved to Seattle from L.A. before opening Tarsan i Jane. Consequently, he believes it’s especially hard to get the ear of the press and to cultivate a following. That’s why he’s taken matters into his own hands to get the word out, currently working with the University of Washington’s Department of Chemistry and doing talks at the UW about food and chemistry. He even has a small lab there where he conducts fermentation projects. His goal is to bring other chefs from outside the city to come and participate in these talks. “I believe this city needs to bring people together.”

Over in Wallingford, veteran restaurant server, manager, and now owner Michelle Magidow is pouring her time and energy into the recently opened Union Saloon. With a decidedly laid-back, old-timey interior that belies elegant, lovingly crafted food, it’s the restaurant you wish lived on your block. But don’t expect one coming to a neighborhood near you anytime soon; Magidow is happy with her sole location. And in her 30 years in the business, she says she’s always worked with hands-on owners, including Renee Erickson at The Whale Wins and Brandon Petit at Delancey. “It’s a really nice place and a business that’s evolving, and I’m always moving toward a state of improvement. I like to greet my guests, see who’s coming into my world for two hours, and make sure they’re going to have a really great time because life is hard.”

And while Doak and Rocher of Brimmer and Heeltap cite the financial difficulty of owning just one place, Magidow sees it as a plus: I’m the only one having to draw a salary out, as opposed to five owners.” Still, she understands the enticement of opening more places, especially in one of the many new developments currently going up in the city. “You have these buildings going up and they make it very advantageous—‘You come in and we’ll help you do your buildout,’ that sort of thing. I wanted to be in an older building, though, so I borrowed money and did my own buildout. My business plan accounts for that over a certain number of years.”

She believes, ultimately, that everyone should do what they want, but she does worry about Seattle’s food scene. “We’ve become this great food city, but what if we start becoming the town where everything’s closing?” That line of thought relates in part to the shortage in culinary staff here. She tells me about a nice young cook she recently spoke to about working for her, but who reasoned that he could find another cooking job with benefits. “I told him to go for it. I can’t offer insurance and pay my chefs well.” She adds that she can barely get insurance for herself. Still, she’s optimistic that cooks and front-of-the-house staff will stay because they can learn from her and because she’s committed to her business. “If we don’t have a dishwasher one night, I’m back there doing dishes too.”

Magidow says that opening the restaurant was super-fun, and she can understand how it might become addictive to do more. In fact, people are already asking her when she plans to open another Union Saloon in their neck of the woods. “If I did that, it wouldn’t be unique anymore,” she concludes. “If I could come up with a whole other concept for a different area, maybe I could succeed. But right now, I’m one girl doing my thing, and I want to simplify my life and rest a little too.”

nsprinkle@seattleweekly.com