Truly, we in the Northwest are privileged above measure by the enormous range of foods and dishes easily accessible to us. We can, should we wish to, dine out on a different world cuisine every night for a month and rarely repeat an experience. So bountiful, indeed, are our choices that they have outrun almost everyone’s ability to absorb information about what we’re eating. And the more obscure the names of dishes on an exotic menu are, the more likely your waitperson will not have enough English to interpret them to your satisfaction.

Seeing “norimaki” on a Japanese menu is all very well, but what if you can’t remember just now what norimaki is? Or a Vietnamese bill of fare mentions “nuoc mum.” You recall that “nuoc” is “sauce,” but does the “mum” refer to that sweet-and-sour dipping sauce you like so much with your spring rolls, or is it Vietnamese for “fish sauce,” which in any more than trace amounts makes you gag? At one of those oh-so-French bistros that seem to be popping up everywhere, the onglet looks appetizing, and sure, you could just ask your waiter what it is. But somehow, you don’t want to give that supercilious Francophone the pleasure of patronizing you.

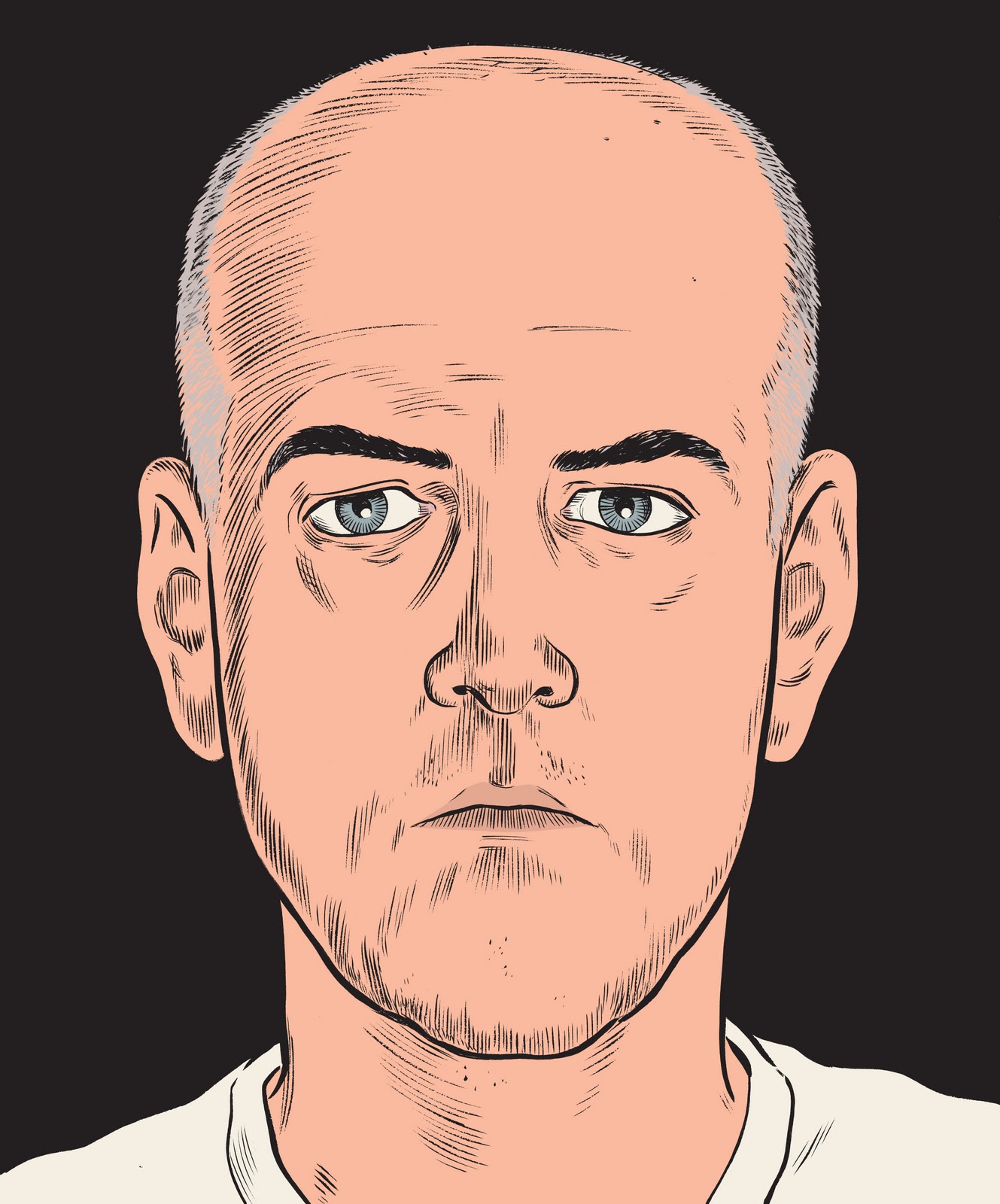

For you and all of us like you, Daniel Blum has a solution. For the nominal sum of $9.95, Mr. Blum will sell you a copy of his Pocket Dictionary of Ethnic Foods (Wordcraft Publishing). Patiently compiled over years of eating out in Washington, D.C., and environs (one of the few cities in America where the food options are even broader than in Seattle), the just-published Dictionary contains culinary terms as yet unknown to the editors of The Food Lover’s Companion or Gourmet, each painstakingly defined and provided with phonetic pronunciation and culinary context.

Multiply the following item by 1,400, and you’ll have some idea how useful this pocket-sized, 220-page compendium is: “opor ayam/oh-poor-eye-ahm/ [Indonesian] pieces of chicken in a mildly spiced sauce made with coconut milk, turmeric, and nuts, originally from Java.” There’s an index of terms by ethnicity, a list of Web sites offering opportunities for in-depth research into specific cuisines, and, perhaps best of all, extensive cross- referencing along with alternate spellings you may come across, e.g.: “ped yang/ bet yang/ [Thai] barbecued duck. also phed-yang, ped-yaang, see also kang-ped bet-yang.” (In case you were wondering, that last item turns out to be barbecued duck with red curry.)

Blum’s achievement is all the more impressive when one learns that it has been created in his time apart from his day job as president of a home-inspection services company.

“The process really started in winter of 2001,” he told me from his home in D.C. “I love food, and I think I’m a very good cook, at least everybody seems to enjoy what I make. But I’m an intuitive cook. I’ve never studied or trained as a chef, and I didn’t have the vocabulary. (I’d never heard of gnocchi before a girlfriend told me what they were.)

“Like everybody else these days, I don’t have much time to cook, and I used to eat out a lot. So when I went to ethnic carryout restaurants, I started taking copies of the menu home with me and researching the terms on the Internet, because often more than half the words used weren’t defined. I spent three years amassing my lists, and then I interviewed chefs and owners of about 40 ethnic restaurants in the D.C. area about my definitions, and it’s a good thing I did, because some of them were way off.”

Blum has published 10,000 copies of his book at his own expense. “I’d like to make my money back, but that’s not really why I did it. I hope others find it useful, but I wanted a book that I could use myself; for instance, the type is large and easy to read, because in a lot of ethnic establishments the lighting level is very low. And I was concerned to keep the price low enough that everyone could afford it.”

The Dictionary is available at University Book Store.