The glossy magazines celebrating the newfound curiosity in vintage drinks may glorify New York City as the origin of cocktail culture, but many a drawling bartender would beg to differ. New Orleans has supplied just as much creative stimulation as New York to the field of libations. No American spirit is so firmly tied to a certain time and place as Herbsaint, the New Orleans pastis whose production goes back to the first days after Prohibition.

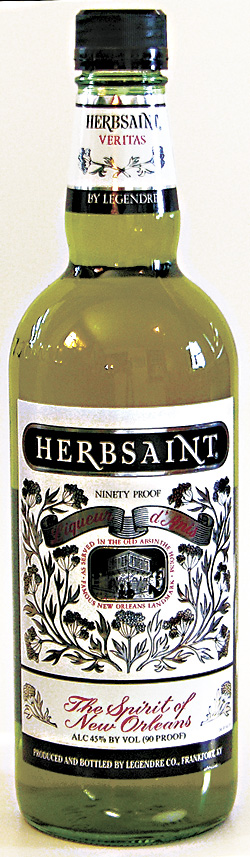

Like all pastis, Herbsaint is merely absinthe without the wormwood—same flavor and color and many of the same ingredients. In fact, the building pictured on every bottle of Herbsaint is none other than the Old Absinthe House, center of turn-of-the-century absinthe culture in New Orleans, and a bar with as enviable a list of patrons as any in the world. In the two centuries the bar has been open, presidents, ne’er-do-wells, and entertainers like Andrew Jackson, Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, and FDR have graced the shop. Amid the spring-breakification of the Vieux Carré today, the Old Absinthe House stands as a staunch reminder of New Orleans’ romantically seedier days.

Absinthe was banned in both America and France around 1915. The big absinthe makers in France quickly developed pastis as a substitute, but Prohibition went into effect in America in 1920. Herbsaint’s founder, J.M. Legendre, obtained one of the first licenses to blend alcohol after Prohibition. Since he was experimenting illegally with the Herbsaint recipe during the ban, he was ready to go the minute Prohibition was lifted. Legendre concocted his recipe based on a business partner’s experiences tasting homemade French pastis during World War I. Legendre put a picture of the Old Absinthe House on the label, a clever marketing ploy as well as a nod to the institution that inspired him.

Smell anchors us to childhood more than any other sense, so I can’t help but associate Herbsaint and its anise-flavored brethren to Good & Plenty. Herbsaint stands out from other, better-known brands of pastis, like Ricard and Pernod, in that it has a more complex flavor. Drinking any pastis straight can be a jolt; you have to dilute it with ice to experience all its flavors. Serving Herbsaint on ice with a little seltzer (the classic New Orleans frappé) mellows the liqueur considerably, releasing hints of vanilla, fennel, and spearmint among the spicy, candied anise flavors.

One classic recipe for an Herbsaint Suissesse requires 2 ounces of Herbsaint, a healthy splash of orgeat (an almond syrup with either rosewater or orange-flower water added), and a big splash of milk. Enjoying one of these with your coffee on a balmy New Orleans morning can cure at least some of what ails you. A few of the menus in my modest collection of old New Orleans bar paraphernalia contain recipes for the Free Love: equal parts gin and Herbsaint vigorously shaken with ice and an egg white; if you’re squeamish about using raw egg in your cocktails, substitute milk or cream. New Orleans’ most famous cocktail is the Sazerac, a souped-up Manhattan of sorts made with rye whiskey. The drink requires a dash of Herbsaint—substituting Pernod would be sacrilege—and another NOLA mainstay, Peychaud’s bitters.

For a local take on Herbsaint, head to Liberty (517 15th Ave. E., www.libertybars.com) and do what I do: Point to the Herbsaint and ask for the bartender’s choice. He or she may boost its flavor with the orange aromatics of gin or perfume your drink with a violet liqueur, but whatever you get, it’ll be heady with the scent of this homegrown pastis.