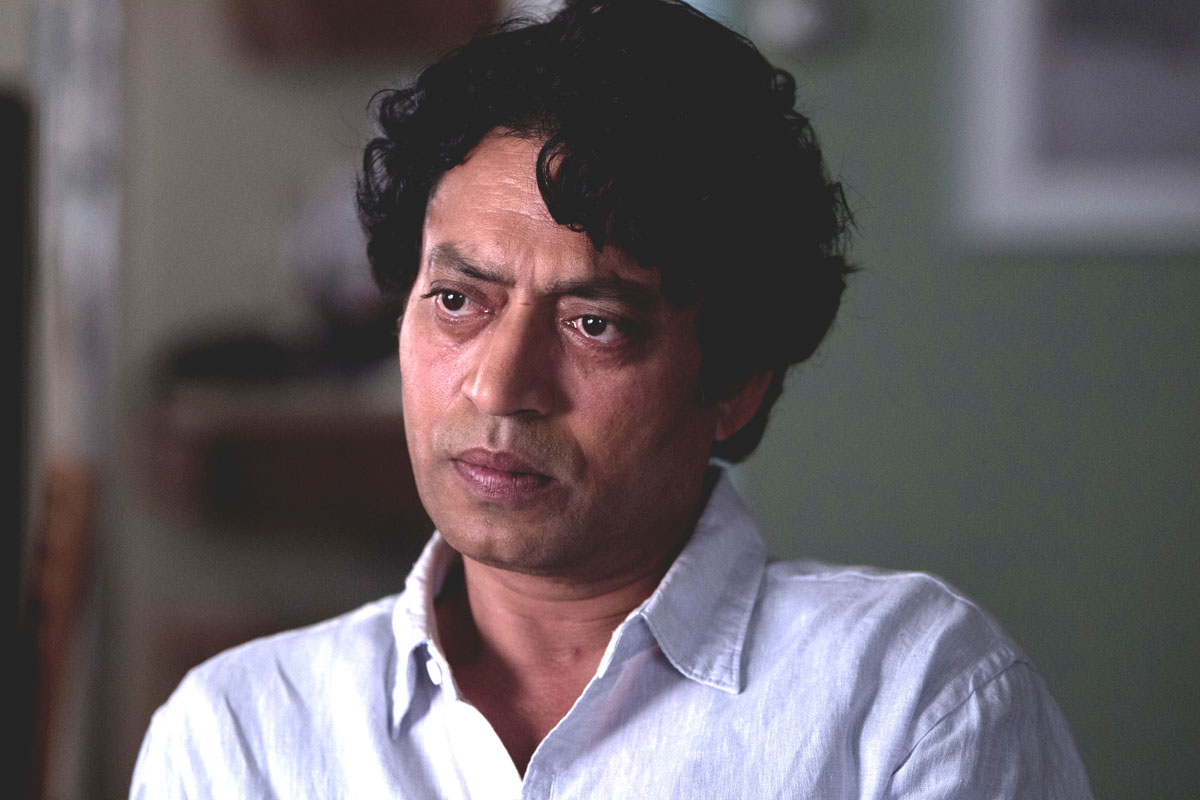

English filmmaker Andrea Arnold’s atypical, impressionistic approach to Emily Brontë is her adaptation’s main hook. As with her Fish Tank and Red Road, Arnold’s new Wuthering Heights is very much about the act of looking. The novel’s tempestuous plot is thus unmercifully filtered through the eyes of Heathcliff, a freed slave and newly adopted member of the Earnshaw family, here presented as a frustrated voyeur—and not at all the white Brit of previous adaptations. When he’s not brooding, Heathcliff is quietly spying on the wild Catherine Earnshaw (Shannon Beer) through cracks in doors or from a distance that’s all the more pronounced by cinematographer Robbie Ryan’s violently jiggly camera movements. Arnold makes the act of looking feel not just forbidden but also downright ugly. Heathcliff is constantly reminded that he can’t really get what he wants because he can’t interact with the Earnshaws on an equal social level—not only because he’s poor and uncouth, as in earlier adaptations, but because here he’s also black. Heathcliff performs a revelatory, wanton act of animal cruelty toward the end of the film, when, now older (and played by James Howson), he can’t flatter himself into thinking that the Earnshaws are secondary characters in his own story. This tragic denouement is reliant on the too-easy bursting of Heathcliff’s narcissistic bubble. Because Arnold sympathizes with the tumultuous and finite perspective that defines her Heathcliff, she indulges rather than explores it; because she traps her viewers with Heathcliff’s murky version of events, there’s no room for enriching subtext here—all the information we need is inscribed on the film’s glassy surface.

Wuthering Heights: Heathcliff as Voyeur and Ex-Slave