Vincent Van Gogh’s life has been fodder for many movies, and it’s easy to understand the appeal: The painter embodies the romantic ideal of the tortured artist, and the subject offers meaty visual possibilities. Plus, the drama! How many biopics build to a scene where the hero slices off part of his own ear? Not many actors can pass up the chance to play that, and the role has served strong performers such as Kirk Douglas (in Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life) and Tim Roth (in Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo). I will argue that the cinema’s best Van Gogh was not seen but heard; in Paul Cox’s lovely 1987 film Vincent, John Hurt recites Vincent’s letters while images of the paintings fill the screen. Yes, everybody’s letters would sound magnificent read aloud by Hurt, but he really brings out the intelligence and sensitivity within Vincent’s raging spirit.

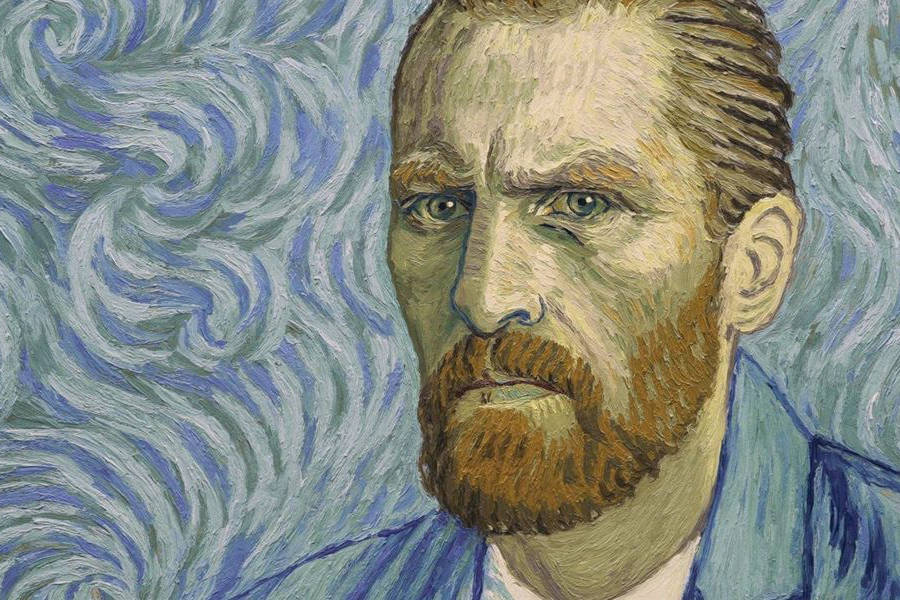

The painter is again little-seen in the animated Loving Vincent, which attempts a unique approach. Like an old Disney hand-drawn cartoon assembled from thousands of individually created cells, Loving Vincent is hand-painted—but in this case, the bulk of the movie is rendered in oil. Directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman hired a team of artists to create tens of thousands of oil paintings in Van Gogh’s style (working from footage shot with actors). Needless to say, this took years.

Does it sound like overkill? It did to me. But this approach almost justifies itself for a couple of reasons, even if it is ultimately overkill. One is the offbeat story: This is not a straight Van Gogh bio but a Citizen Kane-style inquiry in the aftermath of Vincent’s death. The investigator is Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), a young man painted by Van Gogh, who turns up information about the painter’s death while trying to deliver a letter to Vincent’s brother, Theo. Armand encounters the artist’s friends, many of whom are instantly recognizable from Van Gogh portraits: Armand’s father, the heavily bearded postman Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd); Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn); and Gachet’s daughter Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan). It seems Marguerite was sweet on the obsessive painter, but her father might have been jealous of Vincent’s talent. Before long, Loving Vincent turns itself into a murder mystery, picking up on recent theories that Van Gogh may have perished not by suicide but by someone else’s hand.

Everything’s depicted in great churning swirls of paint, vividly picking up on Vincent’s beloved yellows and deep blues. Van Gogh himself appears in flashbacks, a furtive figure in other people’s conflicting memories. These are not in color but in monochrome, a curious choice given how much we tend to imagine Van Gogh’s life in vibrant hues. Eventually these stories come together, and thankfully the film does not in the end insist on a conspiracy theory about the great man’s death. (A certain 1970s song plays over the credits, a real mood-killer.)

Loving Vincent remains frustratingly single-note about its take on the artist, and the re-creation of famous canvases turns the movie-watching experience into a game of spot-the-masterpiece. However, the technique is the other reason to justify the film’s existence. There is something psychedelically exciting about seeing the action unfold, so wild are the colors and designs; too many movies and TV shows opt for dully realistic photography, which makes it especially fun to sit through something this trippy. This alone might win Loving Vincent the Oscar for Animated Feature. Yet even here you can see the flaw in the concept. Van Gogh’s thickly applied paint and frantic brushstrokes already create the astonishing effect of mad, swirling movement. They are motion pictures. Animating them into literal movies is a bit like gilding the sunflower. Loving Vincent, Opens Fri., Oct. 20 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Rated PG-13.

film@seattleweekly.com