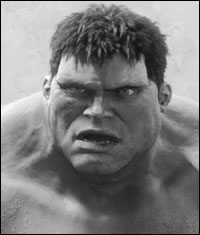

After two installments in the X-Men series, Wolverine is a little closer to learning the secret of his origins at a top-secret military base in the snowy north. In Ang Lee’s The Hulk (which opens Friday, June 20 at Pacific Place and others), Bruce Banner finally learns the secret of his origins at a top-secret military base in the sandy desert. The difference between these two adaptations of suspiciously familiar Cold War comic books is that in the first one we care; in this one we don’t. The audience is always way ahead of Banner (Eric Bana), who, like a Broadway understudy, is regularly cast aside by his big green CGI incarnation, which is the big green selling point to this would-be summer blockbuster.

Well, no matter how many blocks of San Francisco you bust, buster, you haven’t got a movie without a compelling central character. A divided soul, the Hulk needs, yes, to be healed. But neither he nor Banner would have much to say on the couch. Banner starts out as the emotionally withdrawn scientist/loner, and the Hulk represents that alienation on steroids. Yet by the end of the film, though jets and choppers lie crumpled like slain flies, nothing’s changed.

As Wolverine, Hugh Jackman gets to play both sides of his characterenraged, knuckle-knived freak and beer-drinking, tight-jeans misanthrope. But Bana, who showed scary criminal charisma in Chopper and scarier killing prowess in Black Hawk Down, gets neither. Computers create the Hulk, while Banner isn’t created at all. The film’s ’60s prologue briefly suggests how his mad-scientist father somehow went too far with Army-sponsored experiments (starfish, scalpel, self-injection), but even Clark Kent has more personality than Banner. Compared to the big green guy who erupts from within, it’s a case of not id and ego, but of id and empty.

When Jennifer Connelly comes trotting along as Banner’s lab-mate and ex-girlfriend, Betty, it makes no sense that she still has feelings for this repression case. Wolverine’s got sex appeal. Batman smoldering sensuality. Spider-Man is the goofy nerd-next-door a girl secretly wants to kiss. Superman? Opens a car door for a lady. But Hulk? The implications are pornographic. At the preview screening, I heard a few smirks and titters when Betty and the Hulk first play a scene together, he looming above her like King Kong over Fay Wray. Usually, when dating a comic-book icon, a woman gets it both waysthe superhero and his alter ego. Here, neither option seems viable.

THE ONLY REAL passion on display in The Hulk is the conflict between adult children and their overbearing, unloving fathers. Banner rejects his nutty long- lost dad (Nick Nolte, uncombed, unwashed, and unwisely unleashed), while Betty’s military-martinet father (Sam Elliott) rejects her. Oh, boo-hoo. Elliott’s cartoonish crypto-fascist general sneers at the “repressed memories” that torment Banner, but the film takes the matter far more seriously than the Marvel comic book ever did.

The Hulk will be remembered not as an Ang Lee movie but as a special-effects movie, yet even there, apart from the wonder of Connelly’s exquisite eyebrows (more powerful than any gamma ray or genetic mutation), it disappoints. Preview-goers cheered Banner’s Hulkification and subsequent crushing of cars, tanks, and helicoptersbut we’ve been reading that stuff since 1962. (The ’70s TV show also contributes to a feeling of ho-hum familiarityand Bill Bixby gave Banner more humanity.) Only when he’s hopping about the mesas and arches of the azure-skied Southwest like a mammoth green flea is The Hulk pleasing and surprising: the Hulk as the world’s most taciturn sightseeing guide.

In the acting and emoting department, Mr. Hulk compares quite unfavorably with The Two Towers‘ similarly CGI-spawned Gollum. It’s not just because he can’t speak, but because he’s got nothing to articulate. Gollum, half-human and half-whatever, lusts after the ring yet craves Frodo’s acceptance; he’s got some dramatic conflicts beneath that pellucid, scaly skin. Beneath his green, Naughahyde-like hide (picture a mid-’70s couch oozing sweat), the Hulk only wants to rage. Banner only wants to remember, and there’s no reconciling the two.

It’s one thing for Lee to endlessly and annoyingly mimic the comic-book form with split screens and multiple panels (an analogy already made by many previous directors). It’s another for his hokey, literal script to echo comic-book dialogue bubbles. “I’m a scientist,” Connelly declares about 90 minutes into this way-too-long-for-what-it-is film, by which point we’ve had 90 minutes to agree, yes, she is a scientist. Later, her Nobel Prize-worthy diagnosis for the Hulk is, “Just give him a chance to calm down.” Don’t they make Prozac in manhole-cover-sized pills? If played for laughs, ࠬa Mel Brooks in Young Frankenstein, The Hulk would have a reason for being, and the precedent of Peter Boyle and Madeline Kahn’s romance might even give Connelly a chance to sing. Instead, Lee gives us childhood “emotional wounds” that fester into adulthood.

Lee’s sentimentalism is what’s festering. Ever since 1997’s The Ice Storm, which featured real characters with real desires (carnal, charitable, and otherwise), he’s been retreating into Spielberg-like emotional chrysalisclinging to PG-13 in an R-rated world (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is no exception). And Spielberg could’ve done The Hulk in his sleep, with more jokes and less sap. When giant mutant lab animals besiege Connelly in her SUV, their breath and drool fogging her windows, it’s Jurassic Park in a terrarium: The jeopardy is minuscule, inversely proportional to her inevitable Hulked-out rescuer. Some will interpret The Hulk‘s ending as an invitation to a sequel. I’d advise Lee differently: Go back to Connecticut; the adults at the cocktail party are still waiting for you.