Lest we imagine that the publishing industry went to hell only after James Frey and JT LeRoy clambered on board, here comes Lasse Hallström to remind us of a literary dustup emblematic of a much earlier nadir for American mendacity. The Hoax parses the rise and fall of faker Clifford Irving—a stalled minor writer who shot to fame when he claimed to have been approached by the notoriously reclusive aviation billionaire Howard Hughes to write his memoirs—as a symptom of that other lying decade, the 1970s.

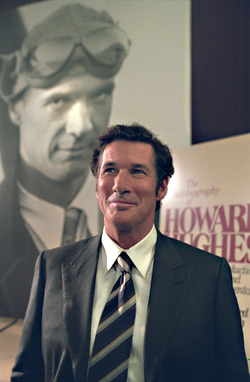

Though I can’t readily summon an American decade that was free of shysters, operators, and runaway gluttons for money and power, The Hoax is strongest when it connects the dots between Irving, who’s played by a wonderfully shifty Richard Gere, and a freshly corporatized book industry. In some of the film’s most delicious scenes, glassy-eyed McGraw-Hill editors and management types (Stanley Tucci, enunciating through contemptuously raised eyebrows) are seen trying to balance their skepticism for Irving’s ludicrously transparent whoppers with their longing to sign up a massive best seller.

Richard Nixon makes a few guest appearances in grainy archival footage as a murky figure in Hughes’ memoirs and, by extension, as the top-down polluter of a culture that, according to the movie, made Irving’s sensational 15 minutes possible. Still, it seems a bit much to hang this entire paranoid age—Vietnam, Watergate, corporate greed, celebrity mania, pointy collars, you name it, they’re all bundled in The Hoax—on a man who cuts no more charismatic a figure than does his president. William Wheeler, who met with Irving and based his own lavishly embroidered screenplay on the author’s post-prison memoir of the affair, found the man affable but “unreadable.” That’s the classic demeanor of the successful con man, who must be winning and elusive at the same time, and who’s always in control of the next move. Gere is a skilled actor with copious experience playing men of fishy motive, but his Irving doesn’t seem capable of pulling off the extravagant stunts that kept his seven-figure book deal alive through successive bouts of doubt and suspicion. Indeed, there’s something slack, nebbishy, and desperate about this orange-haired upstart when, after publication of his latest work has been canceled, he bursts into the office of his editor (Hope Davis) to announce his new project. The schemes he hatches—pilfering the unpublished manuscript of Hughes’ embittered former right-hand man (Eli Wallach), phoning in a raspy Hughes voice from “the Bahamas” (Westchester County), and gathering his increasingly disbelieving publishers on a Manhattan rooftop to await the hermit’s arrival in a helicopter—are the panicky reactions of a man without a plan.

Like all con artists, Irving is a man without a moral core, which is what makes him both seductive and a dangerous betrayer of all those around him, including his good-hearted accomplice (Alfred Molina) and his endlessly forgiving wife (Marcia Gay Harden). But the filmmakers can’t commit to a full-blooded scoundrel. They want us to like Clifford, sort of, and judge him, a little bit. So they light the movie all wishy-washy for ambiguity, and invest this vaporous fraudster with guilt about his serial betrayals—the price he pays for continuing to be bad. The most colorful thing about Gere’s Irving is his dream life, which makes him no different from the rest of us.

To its credit, The Hoax isn’t glib—it doesn’t chalk up Irving’s moral vacuum to anything a bad mommy or daddy did. But there’s no other point of view, either; the film suffers a fatal equivocation over whether to frame him as a caper or an American tragedy. Watching The Hoax, I kept hankering for the antic joie de vivre of Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can, which gave itself wholly over to what we love about the con men who dare to slough off the daily grind and do it their way. They have style to burn, and they don’t give a damn.