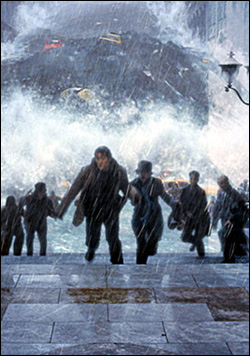

The Day After Tomorrow Now playing at Neptune and others Say what you will about director Roland Emmerich (Godzilla, Independence Day), the man knows how to make a disaster film. His newest exercise in trashing the planet is much, much better than the lizard flick and at least as fun as the alien epic. In Tomorrow, per formula, Emmerich plants likable brainiacs around the world, allowing their personalities to bloom just enough to make us care, sort of, when global warming turns New York into Atlantis and L.A. into Tornado Alley.

When we first encounter strapping scientist Jack Hall (Dennis Quaid), he’s saving a buddy from certain death in Antarctica; a scene or two later, he’s briefing a U.N. conference on the possible consequences of rapid climate change. Soon thereafter, brick-sized hailstones are flattening Tokyo, Los Angeles is being consumed by twisters, and meteorologists the world over are freaking out while shortsighted bureaucrats—and in disaster flicks, is there any other kind?—sit stubbornly on their hands.

Movies like Tomorrow work best in the first reel, when little things begin to go suspiciously awry—geese flocking south by the thousands, sunny California dark with thunderheads—and you can’t help but shudder with suspense and glee. The apocalyptic payoff, though flush with astounding special effects, can’t possibly trump the tingly anticipation. When North America suddenly undergoes the climatic nosedive Hall predicted, his son, Sam (Jake Gyllenhaal)—in Manhattan for an academic competition—holes up in the New York Public Library with the requisite band of colorful, plucky characters: a preppy rich kid, a resourceful homeless man, a nerdy librarian, and the winsome classmate Sam has a massive crush on.

So all the ingredients for an enjoyable world-ender are assembled, and Emmerich orchestrates the mayhem like a pro, injecting just enough human interest and wit to keep us from numbing out. Anti- intellectual as it may seem, I don’t give a heap of hail about the movie’s science, which is reportedly terrible; I waited all spring to watch people flash freeze at 150 below zero, and to hear lines like “We’ve reached the point of critical desalinization!” come out of Dennis Quaid’s mouth. Emmerich even squeezes in a bit of political commentary: When everything above the Mason-Dixon line becomes a block of ice, terrified Southerners head for the Mexican border, which that country’s officials wisely close. The result? Americans stream across illegally and set up refugee camps. Just try finding a social critique like that in Van Helsing. (PG–13) NEAL SCHINDLER

Donnie Darko: The Director’s Cut Opens Wed., June 2, at Varsity and others

If Vegas listed an over/under on “Viewings It Takes the Average Moviegoer to Kinda Understand What the Hell’s Going On in Donnie Darko,” it would be three and I’d put my entire savings down on the over. Of course, that’s rookie writer/ director Richard Kelly’s intent, and it’s a testament to his ability that people actually enjoy talking about Darko (originally released in 2001). David Lynch likewise made his name blending dreamy, borderline-incoherent abstractionism with black humor and compelling, fish-out-of-water protagonists. Each new Lynch effort, subsequently, is an event; if Kelly can maintain that, bravo.

Still, it’s with some skepticism that we greet 20 more minutes of Darko in the dreaded director’s cut format, especially considering Kelly’s assurance that the redux will clarify his personal vision but simultaneously inspire even more divergent interpretations. What we know: The troubled, eponymous ’80s teen protagonist (well played by sleepy-eyed Jake Gyllenhaal) embarks on a journey with a clear beginning and clear end; the tangents of this trip—and the temporal planes they exist upon—are very much a source of debate.

Donnie sleepwalks. This is good and bad—good in that by doing so he avoids getting pulverized by a detached jet engine that crashes into his room; bad in that, once outside, he encounters a hideous 6-foot rabbit who tells him that the world will end 28 days later, on Halloween. Over that period, Donnie commits startling acts of aggression in his waking-dream state, then confesses them—and a litany of life-death insecurities—to his therapist and girlfriend while awake. These quasi- hallucinations, he learns, are tied to an old time-travel book written by a witchlike elderly local, Roberta Sparrow.

Does the new footage enhance and elucidate? For the most part, not really. This new Darko piles on take-’em-or-leave-’em family bonding scenes, many of which are already accessible on the DVD. Kelly does succeed by intermittently displaying text from Sparrow’s The Philosophy of Time Travel, which illuminates identities and motivations without spelling everything out too literally; these on-screen overlays are so quick, undisruptive, and thought-provoking that one wonders why they weren’t included in the original. If you’re already a Darko-phile, you may even want to peruse the complete Philosophy text beforehand, available at www.ruinedeye.com/cd/time1.htm. If you’re a first-timer, hell, you’ve got three screenings to go before you’re ready to really contemplate Darko-isms like “manipulated dead.” Just enjoy the Smurf gang-bang jokes. (R) ANDREW BONAZELLI

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Opens Fri., June 4, at Oak Tree and others

The bespectacled wizard boy may be approaching the days of breaking voice and budding beard, but the spellbinding appeal of the Harry Potter story has not diminished. In this third film in the series, Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) runs away from the Dursleys after magically inflating a visiting aunt who insulted his deceased parents. Back at Hogwarts School, he learns that Sirius Black (Gary Oldman), escaped from prison and somehow tied to the death of Harry’s parents, is hunting him down. The kid can’t catch a break as we watch him dodging werewolves, flying with llama-bird-like creatures (reminiscent of Never-Ending Story), and coping with a screaming shrunken head and a monstrous self-devouring book. All this is conveyed via the seamless visual effects, expert cinematography, and first-rate casting that have helped make the series such a phenomenon. Dame Maggie Smith reprises her role as the frizzy-haired, eccentric Professor McGonagall, while Michael Gambon takes over relatively seamlessly as Dumbledore for the late Richard Harris.

Director Alfonso Cuarón (of Y Tu Mamá También) creates a darker, more sinister atmosphere that aptly represents both the struggle between good and evil in the magic world and the struggles of adolescence for Harry, Ron, and Hermione. Prisoner of Azkaban isn’t as lighthearted or playful as the previous films, as befits the books’ evolution, and it does stumble a bit in conveying its twisting plot. But it makes for a satisfying couple of hours for kids and adults alike. And as for its core audience, you can be sure that Radcliffe’s face will soon be plastered on every preteen girl’s wall and that Azkaban will follow its predecessors as the hot topic in junior highs across America. (PG) HEATHER LOGUE

The Mother Opens Fri., June 4, at Harvard Exit

The Mother Opens Fri., June 4, at Harvard Exit

Movie sex scenes nowadays are dispiritingly perfunctory: plunk some padding in the actress’ crotch and have ’em bang away, maybe knocking over a lamp or two. So it’s a sweet relief to report the arrival of a hot new cinematic bedroom acrobat, Anne Reid. Though her face likely isn’t familiar, her dulcet voice may be—she played the wool-shop owner Wendolene Ramsbottom in Wallace & Gromit: A Close Shave. Startlingly, she’s a sexagenarian sex star, pendulous of neck, with a pretty but saggy ramsbottom and spare tires to spare. Yet her couplings in The Mother boast a genuine eroticism absent from her gym-trim juniors.

Usually, senex sex is treated cartoonishly (think The Graduate or Harold and Maude). Reid’s character, May, is deeply realistic, a rounded-out person in every sense, thanks to her luminously precise performance, a wickedly knowing script by Hanif Kureishi (Sammy and Rosie Get Laid), and ultrasensitive yet unsentimental direction by Roger Michell, who softens and humanizes Kureishi’s icy, nihilist flippancy, sort of the way Tony Scott did Tarantino’s in True Romance.

The setup: May and hubby Toots (Peter Vaughan) visit their horrible narcissist kids and grandkids in London; Toots drops dead. Daughter Paula (Cathryn Bradshaw) and son Bobby (Steven Mackintosh) are too self-absorbed to care much: Bobby’s obsessed with his fancy house and high-risk business, Paula with her pathetic creative- writing career and her elusive, D.H. Lawrence–ish stud-muffin boyfriend, Darren (Daniel Craig), who’s also Bobby’s handyman.

Only May registers any emotion other than peeved selfishness. Stunned by widowhood, she roams the streets in a daze. It’s like the London montages Kureishi used to cook up with Stephen Frears, only instead of a pretentious attempt to paint a society, here we get right inside a particular mind. Cinematographer Alwin Kuchler gives the film a dreamy look like his Morvern Callar. It’s realistic, but packed with little unnaturalmiracles of composition: geometric shadows on tabletops, a pulsing neon billboard reflected in a mirrored skyscraper.

Grief and shock give May wide new eyes to take in the world before it’s all taken away from her, too. When Paula begs May to find out if Darren truly loves her—to really dig into his heart—May gets into his bulgy blue jeans instead. It happens so naturally we don’t hold it against her. The teensy details nail it down: the way everyone treats May like an unperson; Darren’s identification with her mistreatment because her kids condescend to him, too; her tone when first she strips for him in the spare room. “What do you see? A shapeless old lump?” May’s not just being self- deprecating; at her age, there’s no fishing for compliments. She is a lump, but curious, wondering if he can glimpse within her the fiery life that’s awakened behind those quizzically baggy eyes.

Darren is surprisingly uncardboardlike, and the filmmakers nimbly make us forgive his multiple betrayals, cluck maternally along with May at his pill-popping, coke-snorting ways, and generally root for them like they’re the home team instead of a pair of homewreckers. Awkward family encounters and eruptions of domestic chaos get orchestrated with a spontaneity worthy of Altman, only more skillful and pointed. What’s naughty about the movie is not the frank sex but the way it mixes sorrow and muted comedy, and makes us snicker at the sexuality of a woman whose libido and intelligence it also forces us to respect.

One salutes the ghastly apparitions wrought by Mackintosh as the smarmy son and Bradshaw as the daughter who feels failed by the human-potential movement when in fact she’s subhuman and has no potential. The Mother can’t quite figure out how to resolve its dilemmas, but it’s great from moment to moment, and engenders the uncomfortable suspicion that grannies may have more human potential than we realized. (R) TIM APPELO