Mature and complex as its subject, the waning days of a once-enviable marriage, The Door in the Floor (which opens Wednesday, July 14, at the Egyptian) has so much going for it that it seems unfair to single out one element—unfair but irresistible. Yes, it’s impeccably cast and realized: Writer-director Tod Williams has nailed the pricey “simplicity” of Hamptons beach living squarely. And yes, his radical idea to use only the opening section of John Irving’s 1998 generation-spanning novel, A Widow for One Year, has worked surprisingly well. By rearranging slightly, moving it to the present day during one fateful summer, Williams has turned out remarkably faithful to Irving—shrunk to fit.

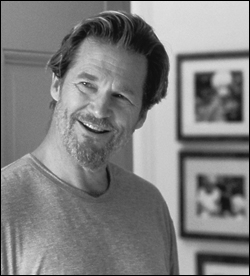

Yet the strongest reason to see Door is Jeff Bridges’ ribald, unsparing portrait of Ted Cole, the book’s echoing presence. Tender, damaged, ruthless, a seducer and a clown, Ted is red meat for Bridges at last. Softly bearded and leonine, padding about in his caftan, wearing his signature plantation hat or cheerfully naked, Ted is a celebrated writer and illustrator. He’s also a self-deprecating poseur. “I’m just an entertainer—who writes children’s books,” he says, more than once, with the same practiced wave of his ink-stained fingers. (Squid ink.)

Ted and his melancholy wife, Marion (Kim Basinger), have just separated, though not over his philandering. A veteran at outlasting those interludes, Marion can chart them perfectly, a Kübler-Ross of seduction. First, Ted sketches an awed Hamptons mother with her child. Then, just the mother. Then the mother naked, and so on, and down it goes. “Innocence, modesty, degradation, shame,” Marion tells a friend. “Mrs. Vaughn is going through the degradation phase.” (As Mimi Rogers plays Mrs. Vaughn, she skips shame and tries for murder.)

Seemingly, Ted has recovered sooner than Marion from the death of their 15- and 17-year-old sons in a car accident more than five years before. Of course, Ted has been arrested for driving drunk so often that he’s lost his license, and his dark minimalist drawings reverberate with fears for lost children. There’s recovery and recovery.

With Ted now in his own place, Marion rambles about their big, handsome, shingled house, but they take gentle turns with Ruthie (Elle Fanning, Dakota’s sister), their clear-eyed 4-year-old. In one of those dreadful ideas that grief can bring, she was conceived to fill the void left by her brothers’ deaths.

Every wall of the big house is filled with black-and-white photographs of Timmy and Tommy, from infancy to Exeter. Instead of nursery rhymes, Ruthie has heard the story behind every picture, recited unvaryingly by her parents. These days, Ted is actually better with the child; Marion, remote, is terrified to love Ruthie for fear of yet another loss.

It’s to this shrine of a house that Ted brings 16-year-old Eddie (fine newcomer Jon Foster), another Exeter boy, to be his assistant for the summer. Someone has to get the squid ink and drive Ted to his assignations, and have his life changed by his first glimpse of Marion.

Williams isn’t simply charting the outcome of an affair—or two affairs—nor even the foundering of a once-glittering marriage; he’s defining the qualities that allow some people to rise above tragedy and some to collapse. And by the film’s end, we’ve seen enough, at close range, to pick the survivors. (Worried moviegoers who don’t know Irving’s book may be cheered to hear that the adult Ruth is just fine. Eventually.)

Basinger has been stymied by her beauty more than once, but not here. Irving might have had a picture of her on his desk as he described Marion, and Williams uses her tremulousness perfectly. The depth of her pathos is as palpable and clear as the bond she and Ted once shared. As for her affair with Eddie, one wrong note and Basinger would lose us. Instead she’s crystalline—not motherly, not seductive—but with a kind of loving straightforwardness about what they both need. (Williams’ tact and steadiness, down to the discreet distance of his camera, is the crucial factor here.) The reward is watching Marion become a figure of amazing resolve, matched by Eddie’s transformation from a star-struck kid to wised-up young man (and writer to be—uh-oh).

Door is a balancing act of major proportions, frightening to think of what it might’ve become without Williams’ stringent taste and intelligence. His first film, 1998’s The Adventures of Sebastian Cole, was well off-beat, with a particularly sharp eye for class and behavior. This one’s a huge leap forward, with luminous cinematography by Terry Stacey (American Splendor), a fine, understated score by Marcelo Zarvos, and nifty details: the snap and wit of the costumes; the inky and mysterious opening credits (by the great Pablo Ferro); the just-right look of the boys’ photographs and Ted’s illustrations (by Bridges himself).

Now, to be crass: Will this be the Bridges performance that finally gets him an overdue Oscar? Only if you’re an optimist of Deaniac proportions. This is a movie fairly drenched in sex, that takes uncommon liaisons in stride and brims with casual and studied nudity—to say nothing of its brief shift into a jittery sex farce (something of an Irving specialty.) Not Academy fodder.

It may be simply the most recent addition to a remarkable list—Starman, Fat City, Cutter’s Way, American Heart, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Fearless, and [your title here] of the best, most consistently eclectic work by one American actor over the last 30-odd years.