Some cities treat their pro sports teams like a close family member. In Seattle, we view them more like a rich, reckless uncle—not someone whose debts we’d pay or help to build a new home. Remember how the Mariners narrowly lost a public vote to build Safeco Field before the legislature bailed them out, and how Qwest Field was funded—on the backs of tourists—by a scant 51.1 to 49.9 percent margin in Paul Allen’s special election.

That’s the context for the documentary Sonicsgate, directed by Seattle filmmaker and fan Jason Reid. (He has also created short videos for SW‘s Web site.) By the time, four years ago, that Howard Schultz’s Sonics ownership group came to feed at the taxpayer trough for yet another makeover of KeyArena, voters were in revolt. Initiative 91, which effectively prohibited city subsidization of sports arenas, passed overwhelmingly in 2006. In what can only be described as a poor-sport temper tantrum with dire consequences, Schultz and his partners then sold the team to an Oklahoma City ownership group at a time when anyone who knew anything about pro basketball knew Oklahoma City was angling for its own team. The leader of that group, Clayton Bennett, declined to consent to an interview for Sonicsgate, as did the other three men—NBA Commissioner David Stern, Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels, and Schultz—Reid portrays as archvillains in his film.

Who wears the white hat? Paradoxically, it may be the guy responsible for I-91, Chris Van Dyk. At least the longtime anti-stadium crusader is intellectually honest, whereas virtually every other character in Reid’s meticulously rendered doc comes out crooked.

In addition to Van Dyk, Reid interviews former players Gary Payton, Sam Perkins, and Nick Collison, announcer Kevin Calabro, former coach George Karl, player-turned-executive Wally Walker, writers Steve Kelley and Sherman Alexie, and many more. (Almost Live‘s John Keister narrates). If you’re not a committed fan like Reid—who used to greet the team at Boeing Field in the wee hours of the morning after road trips—the effect may be too comprehensive. Previously the director of amusing amateur comedies (The Reid-Secrest Olympics, Haymaker & Sally), he throws everything into the pot. He’s deadly serious here, choosing to broadcast not only a loved one’s funeral, but the preceding life, torture, and execution as well. The effect is equal parts enlightening, tragic, and cathartic.

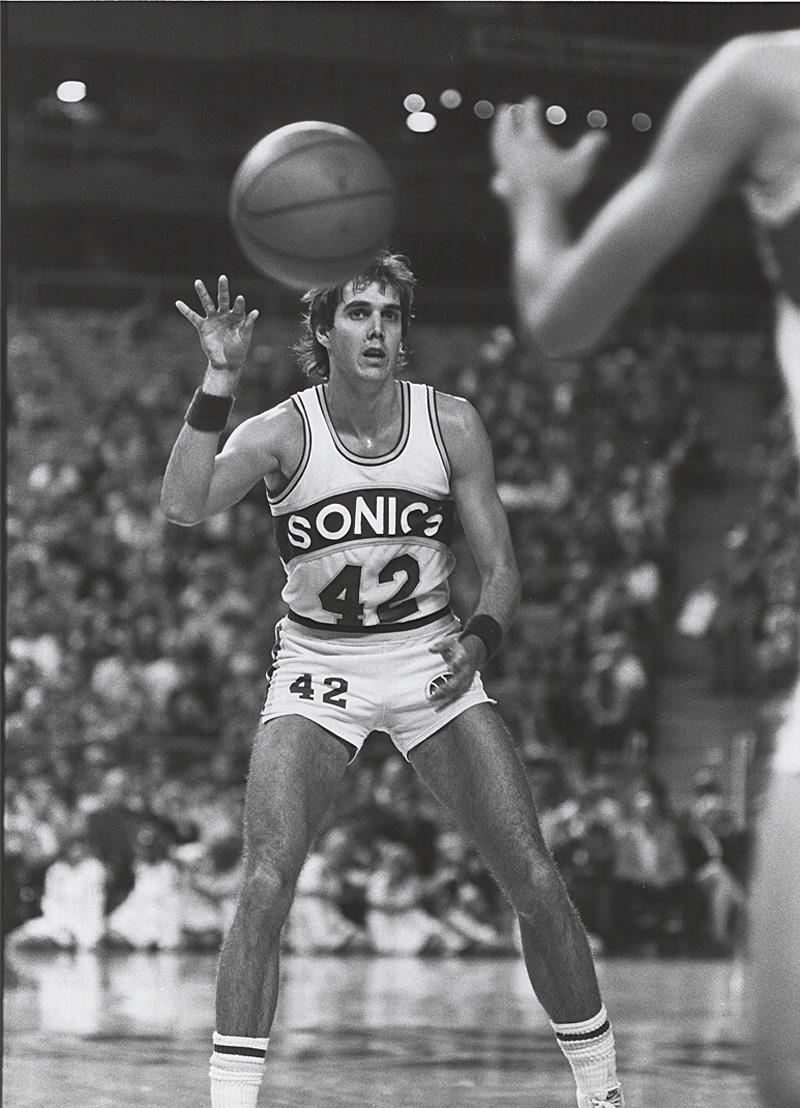

A heartthrob member of the 1979 NBA championship squad, Walker later morphed into the man every Sonics fan loved to hate. He’s also the most fascinating yet frustrating figure in Reid’s film.

During his long tenure in the Sonics front office, Walker was largely credited with making the moves—chief among them the multimillion-dollar signing of seven-foot stiff Jim McIlvaine (who makes a surprise appearance in the doc)—which unraveled the 64-18 squad that made it to the 1996 NBA finals. That was during the team stewardship of Barry Ackerley, who sold the Sonics to the Schultz group in 2001; Walker continued with the club until its next sale. But to his credit, with the Oklahoma City move looking more inevitable by the moment, Walker helped identify a group of wealthy local businessmen—including Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer and Costco’s Jim Sinegal—willing to purchase the team at the 11th hour and contribute $150 million toward the renovation of KeyArena.

Walker says plenty in the film, and his presence is an asset. But Reid never really puts the screws to him. It’s a glaring shortcoming in an otherwise successful venture. It’s also classically Seattle in its inability to take aggressive, timely measures. Likewise, the most genuine effort to keep the Sonics around—the Ballmer bid, the city’s lawsuit to force Bennett’s group to honor the last two years of its lease—came far too late in the game.

There’s a scene toward the end of Sonics-gate in which Reid films himself chasing an SUV whisking Bennett away from the lease-breaking proceedings at the federal courthouse. If Reid had been in Cleveland when the Browns made their escape to Baltimore, he’d have wielded a baseball bat and smashed his way into the vehicle. But that wouldn’t be very Seattle, and explains in part why our Sonics are now Oklahoma City’s Thunder.