Not every member of Homo sapiens who sees Project Nim will be moved to pledge membership in PETA. Still, this documentary biopic of the ’70s chimp picked to endure an “experiment” in simian sign language and general neglect pulls human heartstrings as wrenchingly as any creature feature in the 45 years since Au hasard Balthazar. Snatched from his mother’s arms, then shuttled among surrogate parents who teach him to apologize for his natural rage, the film’s titular subject maintains a more primal connection to the moviegoer than any number of trained monkeys in Hollywood. Heath Ledger got a posthumous Oscar for his animal magnetism; so too should the late Nim Chimpsky (1973–2000).

As in Man on Wire (2008), his superb, Oscar-winning retelling of Philippe Petit’s aerialist jaunt between the Twin Towers, director James Marsh makes such ingenious use of archival footage that one could swear he had shot it himself— which, in the case of a few judiciously selected re-enactments, he did. Following brown-eyed beauty Nim, by turns cuddly and ferocious, from an Oklahoma cage to an Upper West Side brownstone and then back behind bars, Marsh takes a wild story (from Elizabeth Hess’ book Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human) and imbues it with true-life tragicomedy—something akin to the PBS vérité classic An American Family, but with fur. A natural-born rebel in crazy times, young Nim enjoys his Oedipal phase, hits puberty, puffs pot, bites the hand that feeds, and generally goes ape before getting busted by the Man. As the primate’s human sister puts it, “It was the ’70s.”

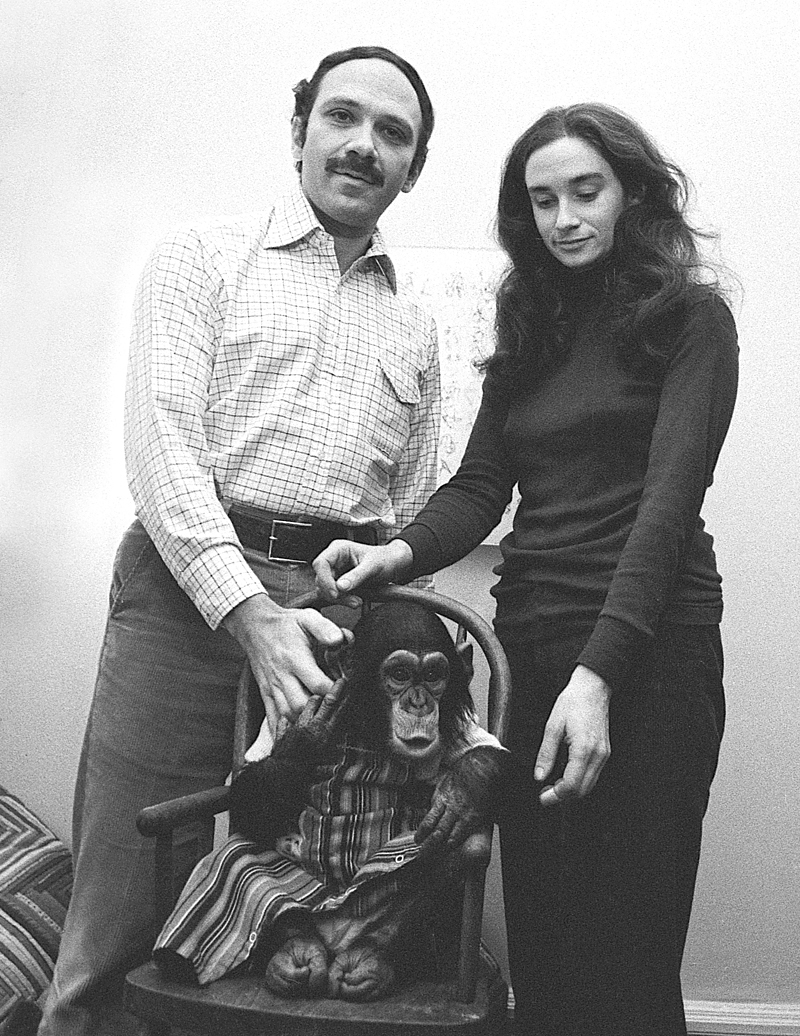

Roughly a year before the beastly Nixon broke free of his own unnatural habitat, a Columbia University prof figured it’d be neat to see whether and how a chimp raised solely among humans could acquire language. To reveal the particular obscenity of the Nim project, Marsh doesn’t have to do much besides turn the camera on Professor Herbert Terrace, a behavioral psychologist (still at Columbia) who tries to argue that his affairs with fellow researchers had absolutely no impact on their scientific collection of data. The prof’s sexual escapades aside, the Nim project appears discreditable by its equally casual methodology. One of Nim’s “mothers” reports that loving and leaving the pissed-off primate was “sort of like breaking up with a bad boyfriend.”

Marsh’s film suggests a more forgivably anthropomorphist metaphor—that poor Nim is like a child of divorce several times over. Brought to the Big Apple at only two weeks of age, the displaced chimp proceeds more or less civilly through diapers and potty training, but terrorizes his first human mom’s poet hubby—not only biting him, but pulling his precious books off the shelves. On the one hand, Nim is a wild animal, of course, but Marsh also pictures him as a troubled teen in a series of profoundly dysfunctional families. Bereft of one wounded caregiver after another, the simian pupil certainly can’t be blamed for learning to attack—or harden his heart. Indeed, watching Marsh’s exquisitely sad film, a human can’t help harboring the occasional fantasy of Nim rising to lead a planet of apes in fiery conquest.

The real story, alas, is more ordinary. A social animal, abandoned by the researchers he thought were family and friends, Nim kills his television, gets a lawyer, and finds a sugar daddy—mixed blessings at best. Nature might appear to win over nurture, except that the latter was clearly closer to abuse. A humane hero does emerge in the third act, though. While Professor Terrace is busy stumping for his late-’70s book on the inconclusiveness of evidence that Nim is smart, a shaggy anti-authoritarian—the last hippie on earth, it seems—comes to the chimp on all fours, offering unconditional friendship, a somewhat better home, and the possibility of more high times.

Nevertheless, Marsh’s film remains a deeply haunting portrait of the unbridgeable gap between kindred species. Nim learns to communicate in sign language (he particularly likes the words “play” and “hug”), but declines—heroically, perhaps—to supply scientific proof that an ape can live comfortably among people who often appear far less intelligent than he is. Naturally, this seals the animal’s fate. And Project Nim guarantees that we’ll never look at zoos—or our pets—in the same way again.