And so the endless campaign wraps up with a flurry of virtual leaders. Richard Nixon will always be part of America’s dreamlife, with or without David Frost. The Bush II legacy will linger for years, even as W. addresses a yearning for closure. Like our president-elect, Milk arrives from left field, right on time. But why Che Guevara, and why now? Who in 2009 could possibly be interested in a four-hour movie on the minutiae of guerrilla warfare?

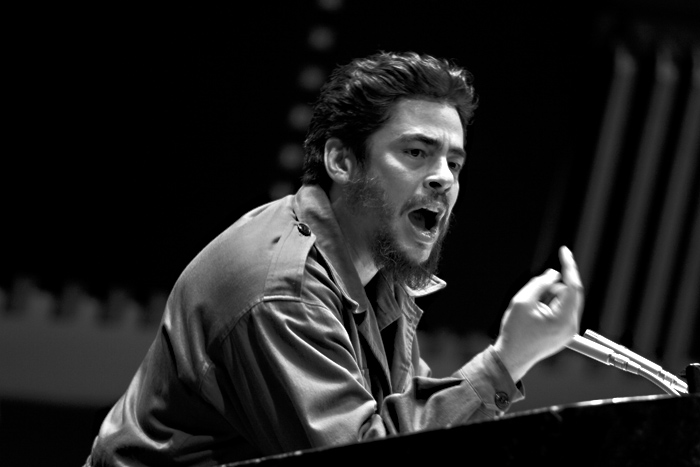

Steven Soderbergh’s Che is neither romantic nor even particularly partisan about the Guevara myth. While the real Che may be (or may once have been) cool, the filmmaker’s attitude is way cooler. Whatever heat star and co-producer Benicio Del Toro brings to the title role, Soderbergh’s project is to search for the technocrat, which is to say himself, in the original revolutionary rock star.

Throughout Che, screened in two parts, the emphasis is on process. Moreover, the movie(s) present the man almost entirely in the context of three events: the Cuban Revolution, the Bolivian debacle, and a 1964 trip to the United Nations. What about Che’s bureaucratic bungling, his persecution of political enemies, his love affairs, his adventures in the Congo? Soderbergh leaves those events out. Everything must be deduced from Che’s behavior under actual or rhetorical fire—he is defined in terms of his desire and capacity to make history.

And Soderbergh wants to make history as well. (Making art is making a lesser form of history.) From Sex, Lies, and Videotape to Ocean’s 11, he’s enjoyed the indie-ist career of any contemporary American filmmaker—whimsically alternating between big-budget crowd-pleasers and pretentious, scruffy experiments.

If Che seems self-reflexive (guerrilla filmmaking as guerrilla warfare), it’s because Soderbergh is less the driven auteur than a highly intelligent artisan who sets himself a problem and goes about solving it. Assuming responsibility for this ambitious, risk-taking, possibly pointless project enabled him a means to identify with his impossibly legendary subject.

Fifty years later, the Cuban Revolution has not yet disappeared as a political issue, and in some respects remains more contemporary than the Third World guerrilla struggles it inspired. Still, Soderbergh’s strategy demands that the viewer project a measure of pathos into Che—or at least an appreciation for the painful failure dramatized on screen.

Diffident or objective—which characterizes Soderbergh’s attitude, and what are his didactic ends? Che might be described as an anti-biopic that nevertheless seeks to humanize its subject (that is, the history that its subject made or failed to make) with a shocking absence of human interest.

This sets up an intriguing dialectic, but whatever Soderbergh’s intentions, Che is most definitely not a movie in the hyper-dramatizing tradition of D.W. Griffith or Steven Spielberg (or, for that matter, Milk). History is not personalized. As a filmmaker, Soderbergh is closer to Otto Preminger in his observational use of the moving camera, or to Roberto Rossellini, whose serenely understated period documentaries—Socrates or The Age of Medici—presented historical facts as though they were commonplace.

At its best, Che is both action film and ongoing argument. Each new camera setup seeks to introduce a specific idea—about Che or his situation—and every choreographed battle sequence is a sort of algorithm in which the camera attempts to inscribe the event that is being enacted. For Che‘s first portion (The Argentine), editing is crucial. Moving on two tracks back and forth in time, it demands an unusually active viewer. The second part (The Guerrilla), a grim tale straightforwardly told, only requires you keep the first playing in your head.

Still, every Bolivian sequence has its Cuban parallel, which is why Che‘s two parts are best seen together. The Guerrilla may be the more realized of the two—and could certainly stand on its own—but it is only comprehensible in the light of The Argentine. Elevating Part II to tragedy, Part I puts some hope in hopelessness—and even in history.