No musician wants to forget the words they’re singing onstage, and one of the dirty little secrets to the endless touring of geezer rock groups—members now in their 60s and 70s—is the use of teleprompters to cue the rebellious lyrics written back when LBJ was president. This affecting and intimate Alzheimer’s-awareness doc, Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me, is more forthright about such stagecraft. When the teleprompter fails during one of the 150 club dates Campbell plays during a 2011–12 farewell tour to support Ghost on the Canvas, the show stops dead. The band—including three of Campbell’s adult children—keeps vamping, while he laughs good-naturedly at his inability to remember the lyrics to “Gentle on My Mind,” which he’s surely sung a million times since 1967.

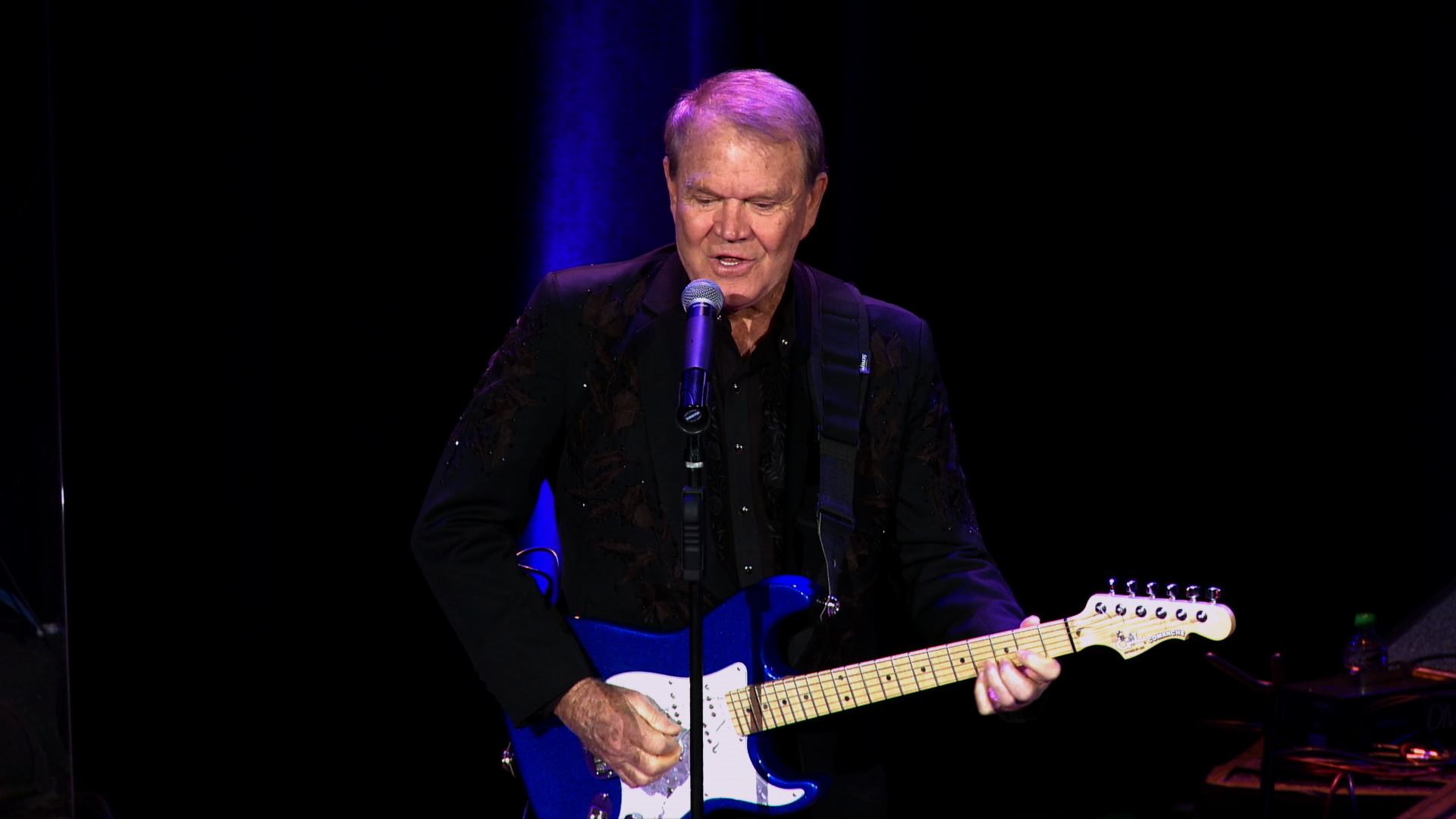

It’s a fairly naked, painful moment during this film by James Keach (of the famous acting clan), made with the complete and somewhat self-serving participation of Campbell’s family. Once Keach shows us the teleprompter, however, we marvel that it displays only the lyrics. It becomes evident here, with some support from Campbell’s neurologist, that his fingers recall more than his mind. He knows all the songs on his “git-tar,” all the chords and changes, all seemingly wired into his synapses after some 60 years as a professional musician. Even while deteriorating, he plays better than many guitarists. And the music seemingly helps stave off decline: “He becomes himself again” onstage, says one son.

And though I’ll Be Me sometimes seems a poignant plea for attention on the part of his family, the onstage Campbell appears perfectly happy—as do his fans, never mind the occasional flubbed song or muffed joke. Offstage, Campbell shows the ornery, disoriented flare-ups well familiar to anyone with Alzheimer’s in the family. To their credit, Keach and Campbell’s wife Kim include enough of these moments to keep the film grounded; it’s not just a promo reel for the family enterprise or a fundraising pitch to Congress. Though the family duly visits Washington, D.C., to lobby and perform; and here’s Bill Clinton—a fellow Arkansan—to add his voice in support.

Also lending support is a long roster of musicians, many with Alzheimer’s in their families: Keith Urban, Sheryl Crow, The Edge, and Jimmy Webb (who wrote Campbell’s “Wichita Lineman” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”). These bland, heartfelt testimonials are consistent with the very family-sanctioned tenor of I’ll Be Me. Campbell had three wives and five other kids before meeting Kim in the early ’80s, and the prior decade’s alcoholism and drug abuse are hardly mentioned. Since then he’s been willingly cleaned up and packaged (also giving his assent to Keach in remarks that must’ve come early in the two-year project). Home-movie clips find their way into frequent montages, but never do we get a sense of the man before the friendly gatekeeper Kim (a former Rockette) or before Alzheimer’s. Heartstrings are being plucked in a familiar Malibu melody (see YouTube for his episode of Behind the Music).

And that is where—despite the universal baby-boomer fears of Alzheimer’s—I’ll Be Me does a small disservice to its subject. If we are to mourn for Campbell, and sympathize with his obviously close, loving family, we really want to know the man better. The whole man. One encomium comes from that obscure banjo player-turned-comedian, Steve Martin, who wrote jokes for Campbell’s 1969–72 variety show on CBS. What he and Keach are too polite to mention is how Campbell replaced the Smothers Brothers (who also employed Martin), whose show was controversially canceled by the network for its political and satirical humor. Campbell was the opposite of that: a genial, apolitical, anti-hippie paladin; a handsome, reassuring presence who entertained and embodied Nixon’s silent majority—even if he didn’t exactly belong to such a square crowd. Why, after all, did John Wayne pick this mediocre actor to costar in True Grit during the height of the counterculture and Vietnam War?

Part of the sadness here is how the real, complete Glen Campbell has been forgotten by all parties involved here. He may not be an important musical figure, but during the zenith of his fame and his final sunset, he durably represented his times.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

GLEN CAMPBELL: I’LL BE ME Opens Fri., Dec. 26 at Sundance Cinemas. Rated PG. 105 minutes.