BAND OF OUTSIDERS

written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard with Anna Karina, Claude Brasseur, and Sami Frey runs Nov. 23-29 at Varsity

THERE’S HARD GODARD and there’s easy Godard. His 1964 Band of Outsiders, a favorite flick of Quentin Tarantino, mercifully tips toward the latter, being one of the least political films of a famously political director during a turbulently political decade. It’s also a watershed movie in a way, a departure from his Breathless-style wanna-be gangsters and molls, a simple, nostalgic, capricious paean to the pulp fiction tropes he was already leaving behind. Ahead lie deconstructionist impulses also apparent in Band, as Godard adds storytelling kinks to the Parisian love triangle between innocent Odile (Anna Karina), Arthur (Claude Brasseur), and Frantz (Sami Frey), who meet in a tedious English class and impulsively decide to burglarize a rich tenant at Odile’s home.

Can you blame them? Their English teacher blathers Romeo and Juliet, but doomed, tragic love is the last thing on their minds. “I’m fed up. It’s impossible to get anywhere,” says Arthur, who suspends his fatalism at the prospect of their big heist. He and his best pal, Frantz, playact at being tough guys, dressing in trench coats and conducting index-finger shoot-outs (“Pow! Pow!”), but they’re very much poseurs, as Band‘s narrator (Godard) makes clear. Their behavior is “in keeping with the tradition of bad B-movies” we’re told, which undercuts the film-noir nihilism they affect.

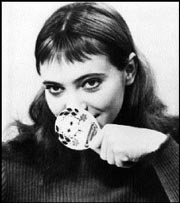

Speeding recklessly through wintry Paris in a battered Simca convertible, our three leads are thus reduced to types by the narrator’s mock-poetic descriptions of cityscapes, mood, and character motivation. “The images speak for themselves,” Godard says, then does the talking for them. Yet somehow the tension between omniscient teller and pulpy tale coalesces into vivid, timeless, irreducible scenes: the three erupting into a cafe line dance (see Pulp Fiction); running through the Louvre in a world record nine minutes, 43 seconds; Karina (Godard’s almost unbearably lovely then-wife) bursting into sad chanson (“Things are not what they are”); an utterly implausible final shoot-out.

None of them are meant seriously, of course, and Band‘s biggest shock (today) comes with a newspaper headline about tribal massacres in Rwanda. One might think, 37 years and nothing’s changed, but that’s not true. No matter how Godard here harkens back to quaint fedoras and six-shooters, his self-conscious narrative chicanery is thoroughly forward-looking. “Classique = moderne,” the English teacher writes on her blackboard, citing T.S. Eliot to her bored students. Here we begin to see Godard’s midcareer pedantry emerging. Theory will soon outpace plot; lovers will count for less than self-reflexive love stories.

“I’m disgusted with life,” says Odile, but you don’t believe her for a second. (Karina’s bursting with life, which may be why she could only stand Godard for seven years.) Instead, it’s Godard’s pessimistic whispering in your ear that rings true. He’s tired of the old Bogie-isms and cinematic gestures; by ’64 he’s outgrown them—and perhaps his popular audience as well. Yet in Band, an accessible but still diffident movie, the director’s ossification still can’t finally diminish his characters’ will to live.